#2022.4 Aprile

Benvenuti nuovi lettori e grazie per il vostro supporto!

Aprile è un mese che vola. Lavoro, Pasqua e poi puff, siamo già alla fine. Quando andavo a scuola si faceva poco o niente in termini di programma, era una catapulta nel delirio di maggio, dove i professori interrogavano a mani basse per recuperare voti e raddrizzare medie.

Ma c’è una cosa di aprile che amo: i giorni vuoti. Non so spiegare il perché, da sempre aprile mi regala quattro o cinque giorni senza impegni, zero. Con le giornate che si allungano, poi, qualche volta ho la sensazione di avere tutto il tempo del mondo. Aprile è un mese che mi mette calma e mi da il tempo per provare cose nuove.

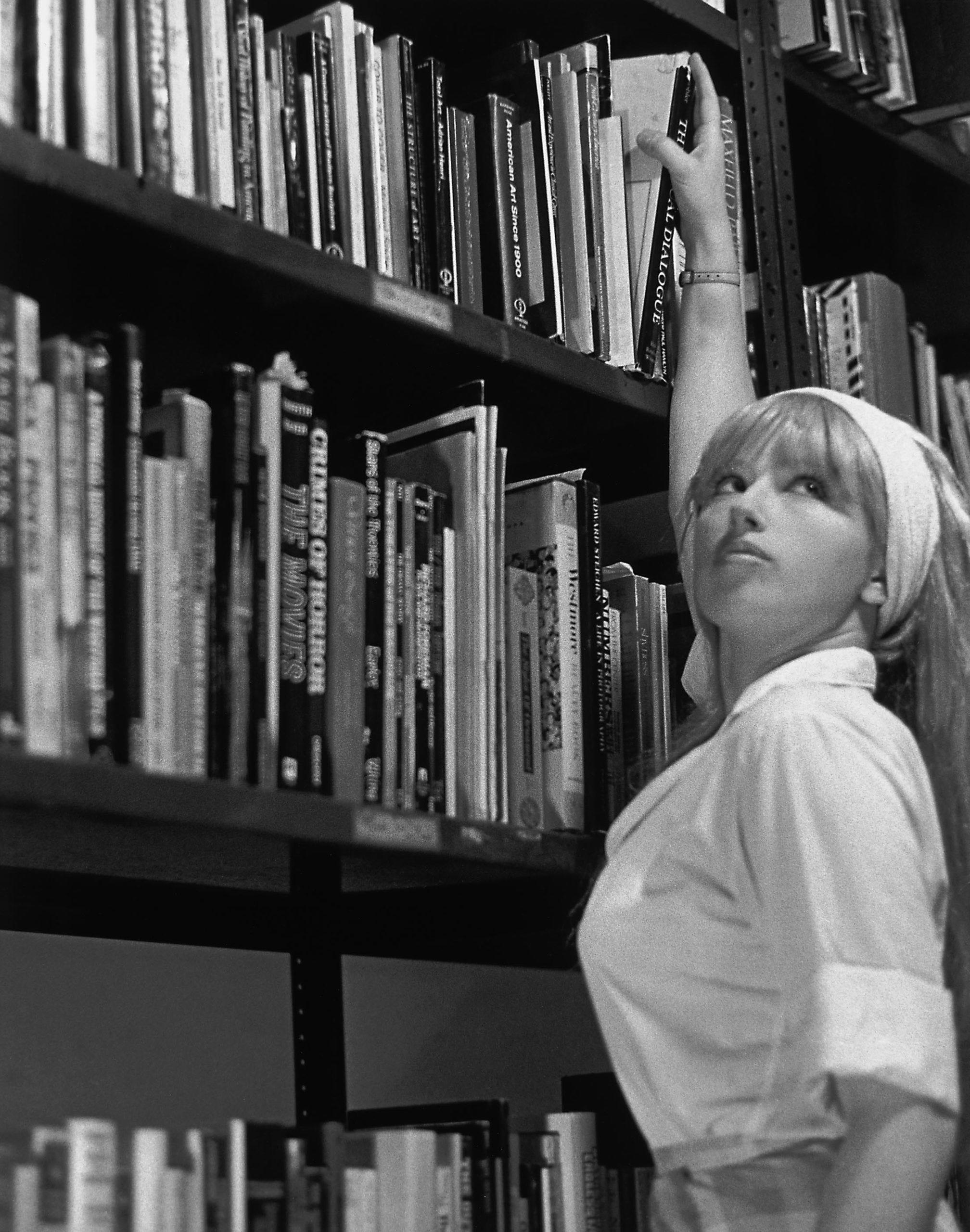

Quest’anno sono riuscita ad infilarci tre sessioni di ritratto con tre persone diverse, oltre al lavoro. Mi fa un po’ strano chiamarle sessioni di ritratto, sono più esplorazioni dove andiamo ad infilarci in posti che più o meno ci sembrano fighi e vediamo cosa succede. Sento di avere un legame sempre più stretto con gli spazi aperti, la natura di montagna e i boschi. Sono sempre più selvatica ed è qualcosa che probabilmente è ora che lasci libera di scorrazzare.

Quando ho iniziato Making Pictures ero sicura che avrei avuto meno tempo libero da dedicare a giocare con la fotografia. E invece sto fotografando di più, con tutti i mezzi possibili, e diventa una pratica più naturale di volta in volta. Sarà che per parlare del fare fotografie bisogna prima farle per davvero.

Argomenti trattati

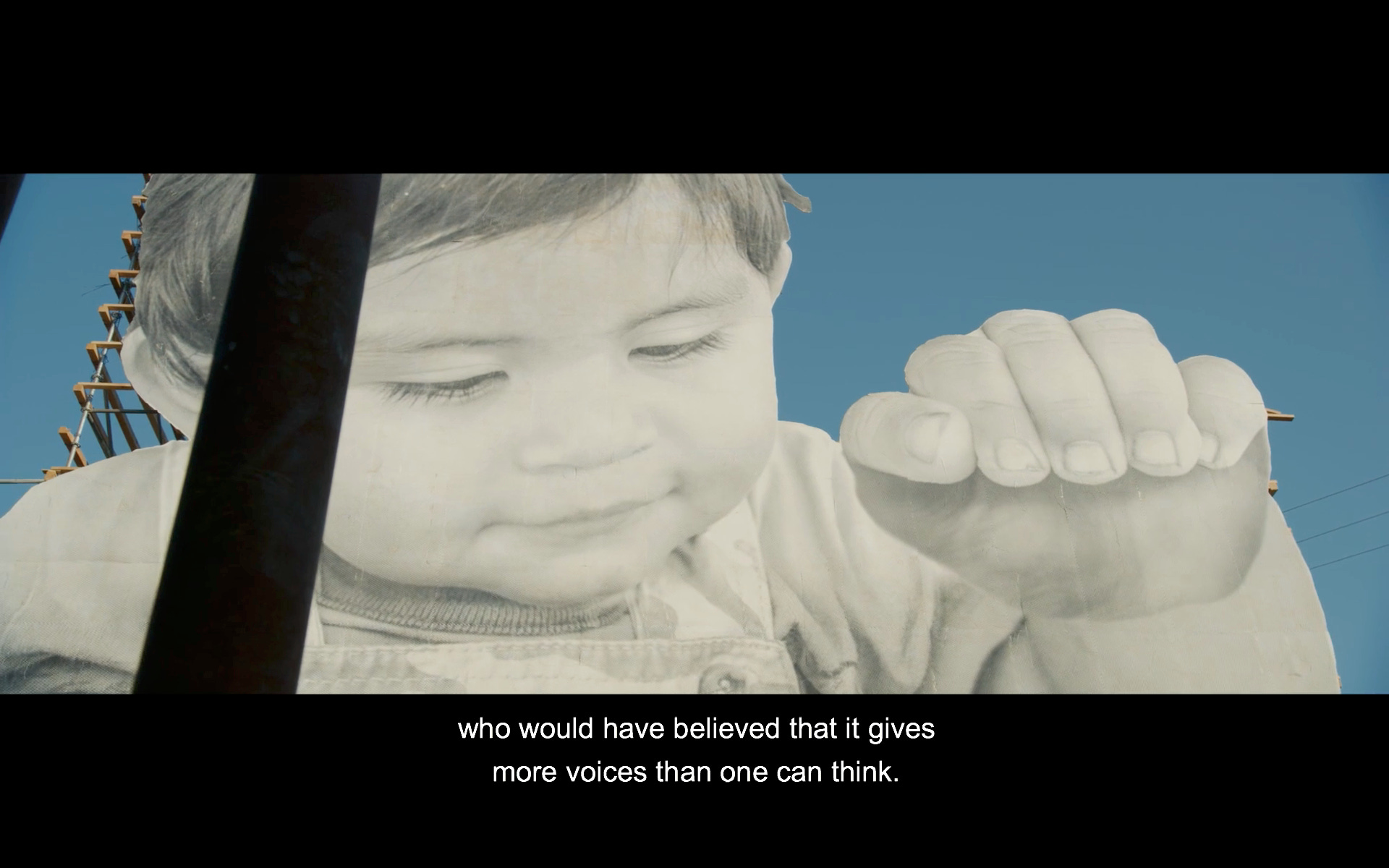

Nel primo articolo di aprile abbiamo parlato di distanza prendendo spunto dalla campagna pubblicitaria Shot in iPhone 6 del 2015.

Le fotografie si trovavano ovunque, a livello di linguaggio visivo la campagna di Apple sfrutta tantissimo a proprio vantaggio la distanza fisica tra osservatore e immagini. Le immagini sono stampate così grandi che l’unico modo per guardarle è da molto lontano. E una fotografia guardata da lontano (o molto piccola, come sullo schermo di un telefono) sembra sempre più nitida, più a fuoco e più bella di quanto non sia se guardata da vicino.

La nuova tecnologia a bordo dell’iPhone 6 riesce a darci lo stesso la percezione di un risultato professionale, fornendo una qualità sufficiente per la distanza (o posizione) dalla quale stiamo guardando.

«So what do the images on display in the World Gallery have in common, other than all having been shot on an iPhone 6? First of all, the World Gallery demonstrates that the iPhone's camera is so powerful that its high-definition pictures can be blown up to billboard-size format (be it with the aid of some image processing). Second, the campaign proves that thanks to the iPhone 6 everyone is a potential artist. As visual studies scholar Marita Sturken writes, Apple's photo advertising is “indicative of the increased blurring of the roles of amateur and professional that has emerged in the digital economy”». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021.

Apple sfrutta la distanza a proprio favore in due modi: allontanando le immagini dall’osservatore le rende, in apparenza, più potenti e, allo stesso tempo, riduce la percezione tra risultato amatoriale e professionale, tra fotografo amatore e artista.

Qualche volta, però, tenere a distanza l’osservatore non è solo un modo per ingannarlo. Distanza e dimensioni sono fattori che vanno tenuti in conto nel processo creativo e può essere un modo per rendere visibile l’invisibile o inevitabile qualcosa che non si vuole guardare.

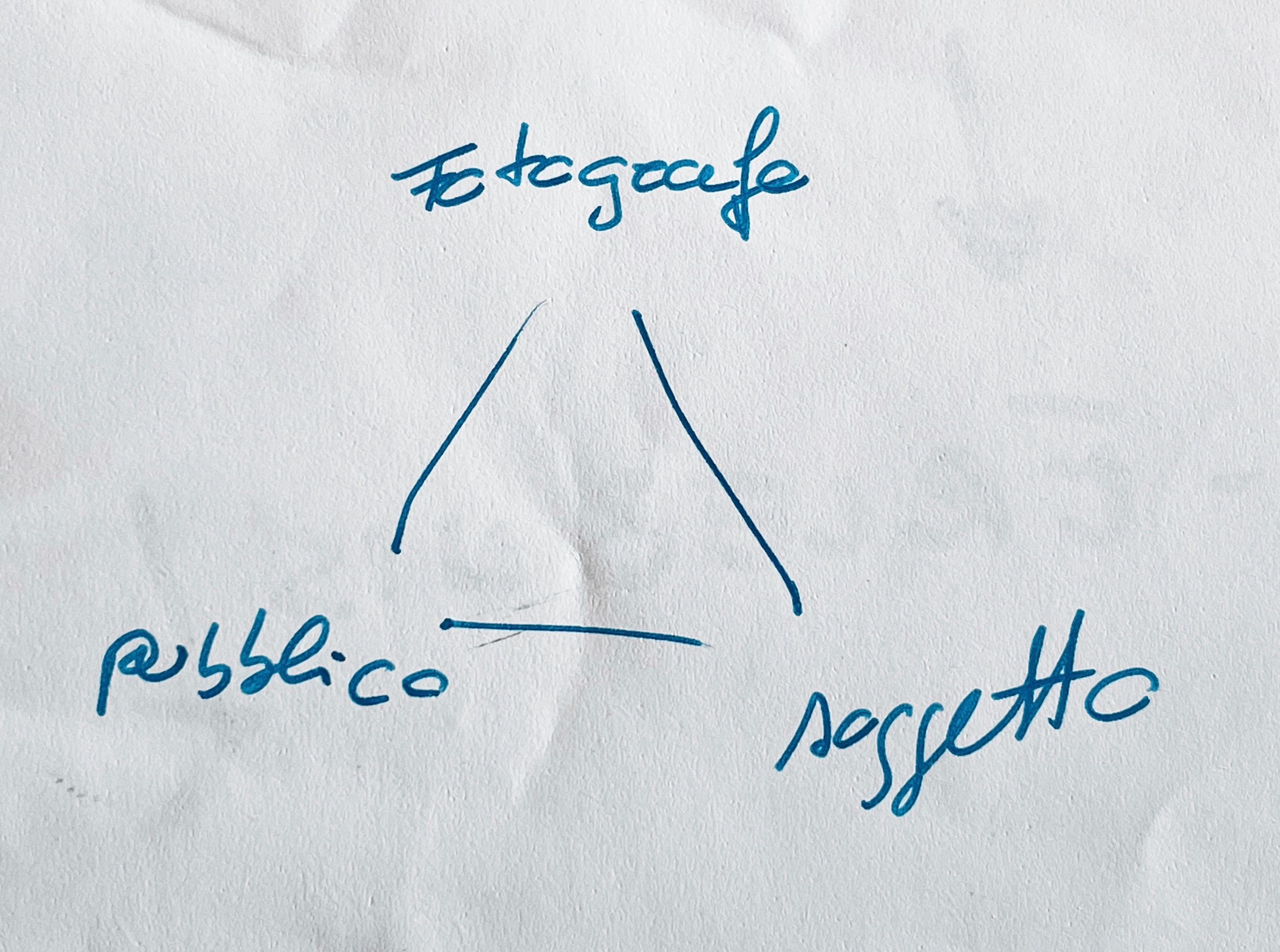

In fotografia possiamo considerare anche altri tipi di distanza oltre a quella spaziale tra immagine e osservatore. L’interpretazione è sempre il risultato di un’interazione tra fotografo - soggetto - pubblico. A volte i vertici possono collidere, a coppie o tutti e tre insieme, l’immagine rimane quello che sta nel mezzo.

Se soggetto e fotografo sono molto vicini tra loro ma distanti dall’osservatore, come nel caso di alcuni lavori di ricerca o d’autore, quello che la fotografia comunica al destinatario potrebbe essere interpretato diversamente dall’osservatore, se non addirittura rifiutato. Può suscitare un effetto disturbante.

Ogni volta che c’è un po’ di distanza la nostra mente riempie le ambiguità inferendo tratti, pensieri e sentimenti. E a proposito di sentimenti: parlando di distanza non intendo solo la dimensione spaziale ma mi riferisco anche a tempo ed emozione. Le fotografie sono macchine del tempo che permettono di estrarre attimi e di rivederli in un altro momento, fuori dal flusso temporale di origine.

«This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards, and forwards…it takes us to places where we ache to go again». Mad Men, The Carousel.

Quello che ci sta intorno e chi amiamo sono qualcosa di unico ma che facciamo fatica a vedere per davvero e senza filtri. A volte la fotografia diventa uno sforzo per ristabilire un contatto perduto con ciò che è.

Nel secondo articolo abbiamo trattato un argomento facile da dire a parole ma difficilissimo da trattare: la rappresentazione nei media. Ho avuto la fortuna avere tra le fonti chi per primo, negli anni ‘60, ha trattato questo tema. Una voce diretta e chiara, di quelle che hanno a cuore quello di cui stanno parlando.

«Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation». George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976.

Quando una società esclude del tutto alcuni individui o interi gruppi dai media, dalle parole scambiate tutti i giorni e dalla cultura in generale mette in atto un vero e propio sterminio simbolico.

Data l’epoca in cui è vissuto, George Gerbner si è occupato principalmente di televisione, ma la sua Teoria della Coltivazione fornisce un’impalcatura adatta ad osservare anche i fenomeni odierni, tra internet e social media.

«“What are the consequences of lifting bits of the culture of everyday life out of their context, repackaging them, and then marketing them back to people?” […] The alternative reality and culture that social media offer, distort people’s perception of reality, numbs critical viewpoints and only exposes users to likeminded individuals». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

Con questo discorso non intendo demonizzare i media. Per quanto ami vivere in mezzo ad un bosco riconosco che la maggior parte di quello che so è conoscenza mediata che non avrei potuto acquisire altrimenti con la stessa facilità.

Resta comunque anche il fatto che i social media sono il prodotto di aziende che devono generare profitto e rispondere ad investitori. Le piattaforme social sono strumenti che vengono usati per vendere prodotti, servizi e ideologie ma sono anche allo stesso tempo dei luoghi dove le persone cercano intrattenimento, socialità e informazione.

«What, Gerbner asks, does this cultivate in our kids, in society? “We live in a world that is erected by the stories we tell [...] and most of the stories are from television. These stories say this is how life works. These are the people who win; these are the people who lose; these are the kinds of people who are villains. It’s a highly stereotypic world day after day. It doesn’t matter whether it’s serious or humorous [...]. There is no more serious business for a culture or a society than the stories you tell your children”». Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

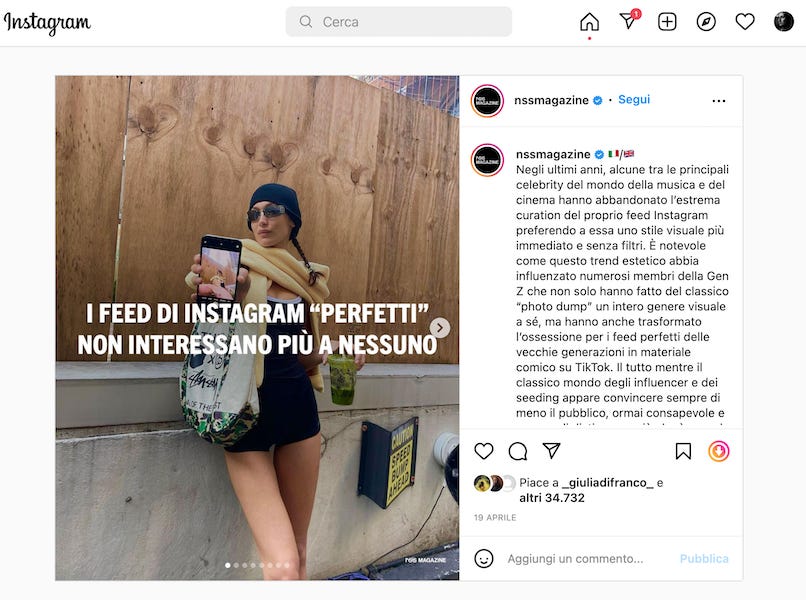

Da un po’ di tempo a questa parte c’è un calo della “perfezione” sui social media, qualcuno parla addirittura di “trionfo della sincerità” ed è una cosa che ha me fa storcere parecchio il naso.

Sono contenta del calo del modello iper perfetto e del ritocco esagerato ma la sovrapposizione di codici comunicativi (persuasivi e informativi) mi lascia molto perplessa. Toglie a me spettatrice gli indizi più evidenti che mi permettono di discriminare bene che cosa sto guardando. E in questo mischiare codici le aziende non hanno come priorità il benessere dei propri clienti, di solito.

Il secondo problema che ho con questo “trionfo della sincerità” è che sembra escludere l’esistenza di una o più immagini pubbliche, dando un po’ per scontato che quello che si vede sui social sia una finestra sincera sulla vita di un individuo e non una delle sue “persone”, dei suoi ruoli, adottati volontariamente o costretti da un contesto.

Appunti e Citazioni

«The World Gallery, in its sublime timeless imagery, puts the viewer at a distance, like much advertising does. As sociologist Michael Schudson writes in Advertising, The Uneasy Persuasion, “advertising looks more real than it should.” Schudson cites sociologist Barbara Rosenblum that in most advertising photography “light is used in conjunction with focus to create a hypertactile effect.” That hypertactile effect is also at play in the World Gallery, whose distancing aesthetic puts the viewer somewhat at a remove from the scenes represented. These scenes appear too real to be taken from everyday life. At the same time, and unlike what is found in most advertising photography, the World Gallery does not display images of the product sold. It is made by means of the product. The World Gallery displays images shot by users, who thanks to Apple, now have a global stage for their photography. By inviting people to identify with these ordinary artists, “we” visitors of the World Gallery are given access to that wonder, too, not just by admiring the photographs—at once art and ads—but also by creating our own images, after having purchased an iPhone of course». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021.

«So what do the images on display in the World Gallery have in common, other than all having been shot on an iPhone 6? First of all, the World Gallery demonstrates that the iPhone's camera is so powerful that its high-definition pictures can be blown up to billboard-size format (be it with the aid of some image processing). Second, the campaign proves that thanks to the iPhone 6 everyone is a potential artist. As visual studies scholar Marita Sturken writes, Apple's photo advertising is “indicative of the increased blurring of the roles of amateur and professional that has emerged in the digital economy”». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021.

«Sin da quando le persone hanno deciso che la fotografia è un’Arte, molti cercano di fare delle fotografie che sembrano Arte, invece di ampliare il concetto di che cosa sia arte o di quale aspetto abbia; come nel creare Dio a immagine dell'uomo invece che il viceversa. Le stampe diventano sempre più grandi e le idee sempre più piccole. Se si guarda con attenzione la maggior parte delle enormi stampe nelle gallerie e nei musei, appare evidente che, per lo più, le immagini non sono molto interessanti, se non si considera il fattore della dimensione. Ricordi la formica? Nel tentativo di rendere le fotografie più di quello che sono intrinsecamente, PERDIAMO ciò che sono intrinsecamente, e la magia scompare. Poiché le fotografie non sono così complesse dal punto di vista materiale, la differenza tra una fotografia ordinaria di qualche cosa e una fotografia che abbia una qualità trascendente o un’altra qualità emotiva può essere estremamente sottile e fragile. Non sto suggerendo che fare stampe di grandi dimensioni sia sbagliato: semplicemente non è per forza un guadagno e può essere una perdita». Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018.

«Normally, if there is any distance from the subject, what a photograph “says” can be read in several ways. Eventually, one reads into the photograph what it should be saying. Splice into a long take of a perfectly deadpan face the shots of such disparate material as a bowl of streaming soup, a woman in a coffin, a child playin with a toy bear, and the viewers - as the first theorist of film, Lev Kuleshov3, famously demonstrated in his workshop in Moscow in the 1920s - will marvel at the subtlety and range of the actor’s expressions». Susan Sontag Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin, 2004.

«This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards, and forwards…it takes us to places where we ache to go again». Mad Men, The Carousel.

«... If we are something, we are our past, aren’t we? Our past is not what can be recorded in a biography or in the newspapers. Our past is our memory. That memory can be hidden or inaccurate—it doesn’t matter. It’s there, isn’t it? It can be a lie but that lie becomes part of our memory, part of us». Conversazione tra Borges e il poeta e saggista argentino Osvaldo Ferrari, This is you here.

«Così ora ho una grande quantità di stampe di prova. Forse una o due sono semplicemente favolose, e lo so. Bene. Le appendo tutte al muro con delle puntine in un posto con una buona luce e in una settimana circa si selezioneranno quasi da sole. Scoprirò come eliminare le più deboli e, fatto più importante, capirò meglio come guardo il mondo. Ancora una volta le fotografie sono la prova di un'esperienza e questa prova conduce a una nuova esperienza». Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018.

«“Unreliable Narrator” plays on narrative interpretation and the existence of “truth” by placing differing versions of the same story together: my family’s, my own narrative, and the pervasiveness of memory through sequences of archive photography, text, my images, and my text. The project is designed to create assumptions of narrative and then works to undermine them […] is a reflexive interrogation of the stories that we tell each other, and ourselves. Using the personal archive as a starting point, I explore estranged relationships within my family and how trauma can continue to impact subsequent generations». Phil Hill, Unreliable Narrator.

«Ma la passante è anche “in lutto”, non bisogna fare di lei un’opera d’arte, quanto piuttosto avvicinarsi alla sua vita, avvertirne la sofferenza, riconoscere in lei una finitudine: su questo piano ovviamente hanno luogo i veri incontri». Yves Bonnefoy, Poesia e fotografia. O Barra O Edizioni, 2015.

«It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to». J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings.

«Cultivation analysis asks, in other words, to what extent television “cultivates” our understanding of the world.

[…] One of the basic premises of Gerbner’s cultivation analysis is that television violence is not simple acts but rather “a complex social scenario of power and victimization”. What matters is not so much the raw fact that a violent act is committed but who does what to whom. Gerbner is as insistent about this as he is about anything, repeating it in all his writings and speeches. “What is the message of violence?” he asks me rhetorically over tea in his office at the University of Pennsylvania, a cozy, windowless rectangle filled with books, pictures, and objets d'art. “Who can get away with what against whom?”» Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

«Chiunque riceve un’ informazione, specialmente se fotografica, deve chiedersi perché e in che forma sia utile a chi la trasmette; poi chiedersi ancora in che modo nuoce a chi la riceve». Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo. Mondadori, 2007.

«In pointing to certain elements in ads, or movies, or fashion, I’m not ignoring the differences in how people may see things, but deliberately trying to direct your attention to what I see as significant. I’m making an argument, and you may or may not find it convincing. You might think - as my students sometimes do - that I’m “making too much” out of certain elements. Or your own background, values, “ways of seeing” may enable you to discern things that I do not. Or it may be that even as I offer my ideas, the cultural context has already begun to shift in ways that answer my interpretation or make it obsolete. Cultural interpretation is an ongoing, always incomplete process, and no one gets the final word». Susan Bordo, The Male Body. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2000.

«We walk around with media-generated images of the world, using them to construct meaning about political and social issues. The lens through which we receive these images is not neutral but evinces the power and point of view of the political and economic elites who operate and focus it. And the special genius of this system is to make the whole process seem so normal and natural that the very art of social construction is invisible». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

«Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation». George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976.

«“What are the consequences of lifting bits of the culture of everyday life out of their context, repackaging them, and then marketing them back to people?” […] The alternative reality and culture that social media offer, distort people’s perception of reality, numbs critical viewpoints and only exposes users to likeminded individuals». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

«What, Gerbner asks, does this cultivate in our kids, in society? “We live in a world that is erected by the stories we tell [...] and most of the stories are from television. These stories say this is how life works. These are the people who win; these are the people who lose; these are the kinds of people who are villains. It’s a highly stereotypic world day after day. It doesn’t matter whether it’s serious or humorous [...]. There is no more serious business for a culture or a society than the stories you tell your children.”

[...]

Of course, stories have always been used to teach and control [...]. What is new is that the stories are standardized and commercialized. “For the first time in human history,” Gerbner says, “the stories are told not by parents, not by the school, not by the church, not by the community or tribe and in some cases not even by the native country but by a relatively small and shrinking group of global conglomerates with something to sell. This changes in a very fundamental way the cultural environment into which our children are born, grow up, and become socialized.” It used to be that scary stories were told to children face-to-face, so they could be modulated, softened, individually tailored by the parents or the community depending on the situation and the desired lesson. Children today, in contrast, grow up in a cultural environment that is designed to the specifications of a marketing strategy». Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

«I suppose unconsciously, or semiconsciously at bet, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women. The characters weren’t dummies; they weren’t just airhead actresses. They were women struggling with something, but I didn’t know what. The clothes make them seem a certain way, but then, you look at their expression, however slight it may be, and wonder if maybe “they” are not what the clothes are communicating. I wasn’t working with a raised “awareness”, but I definitely felt that the characters are questioning something – perhaps being forced into a certain role. At the same time, those roles are in film: the women aren’t being lifelike; they are acting. There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity». Cindy Sherman, Making of Untitled. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, Public Delivery, 2022.

«Nel mito, la leggenda, la fiaba, il racconto, la novella, l’epica, la storia, la tragedia, il dramma, la commedia, il mimo, la pittura, nei mosaici, nei fumetti, nelle notizie, nella conversazione, in tutti i luoghi e in tutte le società. Indipendentemente da una suddivisione in buona e cattiva letteratura, la narrazione è internazionale, transtorica, transculturale: essa è semplicemente là, come la vita stessa». Roland Barthes, 1977.

«La creazione narrativa della realtà non è sottoposta all’obbligo di dimostrazione formale, ma risponde al criterio della verosimiglianza. Agisce nel doppio scenario di azione (fare cose) e coscienza (osservare ciò che si fa e rifletterci su). Si interessa al particolare e al concreto, più che al generale e all’astratto, lasciandolo al pensiero paradigmatico logico-scientifico, interessato agli aspetti concettuali più universali e generali. Crea legami fra l’ordinario e lo straordinario, perché la storia inizia quando il protagonista varca la soglia per inoltrarsi nell’avventura straordinaria, e poi la varca di nuovo per tornare nel mondo ordinario. Secondo Bruner si tratta di uno dei meccanismi psicologici fondamentali per l’individuo e per i gruppi sociali e culturali […]. L’intelligenza narrativa è un’intelligenza ermeneutica, interpretativa. Si tratta di una capacità che va alla ricerca del significato di ciò che accade nella vita, della conoscenza di sé e degli altri, sia come singoli sia quale complesso inserito in un determinato assetto culturale». Bruner e il pensiero narrativo.

Bibliografia

Yves Bonnefoy, Poesia e fotografia. O Barra O Edizioni, 2015.

Susan Bordo, The Male Body. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2000.

Bruner e il pensiero narrativo.

George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976.

Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo. Mondadori, 2007.

David G. Myers, Jean M. Twenge, Elena Marta e Maura Pozzi, Psicologia sociale. McGraw Hill Education, III edizione 2017.

Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021.

Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018.

Cindy Sherman, Making of Untitled. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, Public Delivery, 2022.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin, 2004.

Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings.

Libri fotografici e Serie

Roger Ballen, Asylum of the Birds.

Albarrán Cabrera, This is you here.

JR, Giants, Kikito, Border Mexico-USA, 2017.

Phil Hill, Unreliable Narrator.

Pablo Rochat, Also Shot on iPhone, 2015.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills.

Giancarlo Shibayama, The Shibayamas.

Iiu Susiraja, Lovely wife, 2018.

Video

![Aprile è un mese che vola. Lavoro, Pasqua e poi puff, siamo già alla fine. Quando andavo a scuola si faceva poco o niente in termini di programma, era una catapulta nel delirio di maggio, dove i professori interrogavano a mani basse per recuperare voti e raddrizzare medie. Ma c’è una cosa di aprile che amo: i giorni vuoti. Non so spiegare il perché, da sempre aprile mi regala quattro o cinque giorni senza impegni, zero. Con le giornate che si allungano, poi, qualche volta ho la sensazione di avere tutto il tempo del mondo. Aprile è un mese che mi mette calma e mi da il tempo per provare cose nuove. Quest’anno sono riuscita ad infilarci tre sessioni di ritratto con tre persone diverse, oltre al lavoro. Mi fa un po’ strano chiamarle sessioni di ritratto, sono più esplorazioni dove andiamo ad infilarci in posti che più o meno ci sembrano fighi e vediamo cosa succede. Sento di avere un legame sempre più stretto con gli spazi aperti, la natura di montagna e i boschi. Sono sempre più selvatica ed è qualcosa che probabilmente è ora che lasci libera di scorrazzare. Quando ho iniziato Making Pictures ero sicura che avrei avuto meno tempo libero da dedicare a giocare con la fotografia. E invece sto fotografando di più, con tutti i mezzi possibili, e diventa una pratica più naturale di volta in volta. Sarà che per parlare del fare fotografie bisogna prima farle per davvero. Argomenti trattati Nel primo articolo di aprile abbiamo parlato di distanza prendendo spunto dalla campagna pubblicitaria Shot in iPhone 6 del 2015. Le fotografie si trovavano ovunque, a livello di linguaggio visivo la campagna di Apple sfrutta tantissimo a proprio vantaggio la distanza fisica tra osservatore e immagini. Le immagini sono stampate così grandi che l’unico modo per guardarle è da molto lontano. E una fotografia guardata da lontano (o molto piccola, come sullo schermo di un telefono) sembra sempre più nitida, più a fuoco e più bella di quanto non sia se guardata da vicino. La nuova tecnologia a bordo dell’iPhone 6 riesce a darci lo stesso la percezione di un risultato professionale, fornendo una qualità sufficiente per la distanza (o posizione) dalla quale stiamo guardando. «So what do the images on display in the World Gallery have in common, other than all having been shot on an iPhone 6? First of all, the World Gallery demonstrates that the iPhone's camera is so powerful that its high-definition pictures can be blown up to billboard-size format (be it with the aid of some image processing). Second, the campaign proves that thanks to the iPhone 6 everyone is a potential artist. As visual studies scholar Marita Sturken writes, Apple's photo advertising is “indicative of the increased blurring of the roles of amateur and professional that has emerged in the digital economy”». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021. Apple sfrutta la distanza a proprio favore in due modi: allontanando le immagini dall’osservatore le rende, in apparenza, più potenti e, allo stesso tempo, riduce la percezione tra risultato amatoriale e professionale, tra fotografo amatore e artista. Qualche volta, però, tenere a distanza l’osservatore non è solo un modo per ingannarlo. Distanza e dimensioni sono fattori che vanno tenuti in conto nel processo creativo e può essere un modo per rendere visibile l’invisibile o inevitabile qualcosa che non si vuole guardare. In fotografia possiamo considerare anche altri tipi di distanza oltre a quella spaziale tra immagine e osservatore. L’interpretazione è sempre il risultato di un’interazione tra fotografo - soggetto - pubblico. A volte i vertici possono collidere, a coppie o tutti e tre insieme, l’immagine rimane quello che sta nel mezzo. Se soggetto e fotografo sono molto vicini tra loro ma distanti dall’osservatore, come nel caso di alcuni lavori di ricerca o d’autore, quello che la fotografia comunica al destinatario potrebbe essere interpretato diversamente dall’osservatore, se non addirittura rifiutato. Può suscitare un effetto disturbante. Ogni volta che c’è un po’ di distanza la nostra mente riempie le ambiguità inferendo tratti, pensieri e sentimenti. E a proposito di sentimenti: parlando di distanza non intendo solo la dimensione spaziale ma mi riferisco anche a tempo ed emozione. Le fotografie sono macchine del tempo che permettono di estrarre attimi e di rivederli in un altro momento, fuori dal flusso temporale di origine. «This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards, and forwards…it takes us to places where we ache to go again». Mad Men, The Carousel. Quello che ci sta intorno e chi amiamo sono qualcosa di unico ma che facciamo fatica a vedere per davvero e senza filtri. A volte la fotografia diventa uno sforzo per ristabilire un contatto perduto con ciò che è. Nel secondo articolo abbiamo trattato un argomento facile da dire a parole ma difficilissimo da trattare: la rappresentazione nei media. Ho avuto la fortuna avere tra le fonti chi per primo, negli anni ‘60, ha trattato questo tema. Una voce diretta e chiara, di quelle che hanno a cuore quello di cui stanno parlando. «Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation». George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976. Quando una società esclude del tutto alcuni individui o interi gruppi dai media, dalle parole scambiate tutti i giorni e dalla cultura in generale mette in atto un vero e propio sterminio simbolico. Per approfondire vi rimando alle parole di Marina Cuollo su Vanity Fair. Data l’epoca in cui è vissuto, George Gerbner si è occupato principalmente di televisione, ma la sua Teoria della Coltivazione fornisce un’impalcatura adatta ad osservare anche i fenomeni odierni, tra internet e social media. «“What are the consequences of lifting bits of the culture of everyday life out of their context, repackaging them, and then marketing them back to people?” […] The alternative reality and culture that social media offer, distort people’s perception of reality, numbs critical viewpoints and only exposes users to likeminded individuals». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018. Con questo discorso non intendo demonizzare i media. Per quanto ami vivere in mezzo ad un bosco riconosco che la maggior parte di quello che so è conoscenza mediata che non avrei potuto acquisire altrimenti con la stessa facilità. Resta comunque anche il fatto che i social media sono il prodotto di aziende che devono generare profitto e rispondere ad investitori. Le piattaforme social sono strumenti che vengono usati per vendere prodotti, servizi e ideologie ma sono anche allo stesso tempo dei luoghi dove le persone cercano intrattenimento, socialità e informazione. «What, Gerbner asks, does this cultivate in our kids, in society? “We live in a world that is erected by the stories we tell [...] and most of the stories are from television. These stories say this is how life works. These are the people who win; these are the people who lose; these are the kinds of people who are villains. It’s a highly stereotypic world day after day. It doesn’t matter whether it’s serious or humorous [...]. There is no more serious business for a culture or a society than the stories you tell your children”». Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997. Da un po’ di tempo a questa parte c’è un calo della “perfezione” sui social media, qualcuno parla addirittura di “trionfo della sincerità” ed è una cosa che ha me fa storcere parecchio il naso. Sono contenta del calo del modello iper perfetto e del ritocco esagerato ma la sovrapposizione di codici comunicativi (persuasivi e informativi) mi lascia molto perplessa. Toglie a me spettatrice gli indizi più evidenti che mi permettono di discriminare bene che cosa sto guardando. E in questo mischiare codici le aziende non hanno come priorità il benessere dei propri clienti, di solito. Il secondo problema che ho con questo “trionfo della sincerità” è che sembra escludere l’esistenza di una o più immagini pubbliche, dando un po’ per scontato che quello che si vede sui social sia una finestra sincera sulla vita di un individuo e non una delle sue “persone”, dei suoi ruoli, adottati volontariamente o costretti da un contesto. Appunti e Citazioni «The World Gallery, in its sublime timeless imagery, puts the viewer at a distance, like much advertising does. As sociologist Michael Schudson writes in Advertising, The Uneasy Persuasion, “advertising looks more real than it should.” Schudson cites sociologist Barbara Rosenblum that in most advertising photography “light is used in conjunction with focus to create a hypertactile effect.” That hypertactile effect is also at play in the World Gallery, whose distancing aesthetic puts the viewer somewhat at a remove from the scenes represented. These scenes appear too real to be taken from everyday life. At the same time, and unlike what is found in most advertising photography, the World Gallery does not display images of the product sold. It is made by means of the product. The World Gallery displays images shot by users, who thanks to Apple, now have a global stage for their photography. By inviting people to identify with these ordinary artists, “we” visitors of the World Gallery are given access to that wonder, too, not just by admiring the photographs—at once art and ads—but also by creating our own images, after having purchased an iPhone of course». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021. «So what do the images on display in the World Gallery have in common, other than all having been shot on an iPhone 6? First of all, the World Gallery demonstrates that the iPhone's camera is so powerful that its high-definition pictures can be blown up to billboard-size format (be it with the aid of some image processing). Second, the campaign proves that thanks to the iPhone 6 everyone is a potential artist. As visual studies scholar Marita Sturken writes, Apple's photo advertising is “indicative of the increased blurring of the roles of amateur and professional that has emerged in the digital economy”». Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021. «Sin da quando le persone hanno deciso che la fotografia è un’Arte, molti cercano di fare delle fotografie che sembrano Arte, invece di ampliare il concetto di che cosa sia arte o di quale aspetto abbia; come nel creare Dio a immagine dell'uomo invece che il viceversa. Le stampe diventano sempre più grandi e le idee sempre più piccole. Se si guarda con attenzione la maggior parte delle enormi stampe nelle gallerie e nei musei, appare evidente che, per lo più, le immagini non sono molto interessanti, se non si considera il fattore della dimensione. Ricordi la formica? Nel tentativo di rendere le fotografie più di quello che sono intrinsecamente, PERDIAMO ciò che sono intrinsecamente, e la magia scompare. Poiché le fotografie non sono così complesse dal punto di vista materiale, la differenza tra una fotografia ordinaria di qualche cosa e una fotografia che abbia una qualità trascendente o un’altra qualità emotiva può essere estremamente sottile e fragile. Non sto suggerendo che fare stampe di grandi dimensioni sia sbagliato: semplicemente non è per forza un guadagno e può essere una perdita». Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018. «Normally, if there is any distance from the subject, what a photograph “says” can be read in several ways. Eventually, one reads into the photograph what it should be saying. Splice into a long take of a perfectly deadpan face the shots of such disparate material as a bowl of streaming soup, a woman in a coffin, a child playin with a toy bear, and the viewers - as the first theorist of film, Lev Kuleshov3, famously demonstrated in his workshop in Moscow in the 1920s - will marvel at the subtlety and range of the actor’s expressions». Susan Sontag Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin, 2004. «This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards, and forwards…it takes us to places where we ache to go again». Mad Men, The Carousel. «... If we are something, we are our past, aren’t we? Our past is not what can be recorded in a biography or in the newspapers. Our past is our memory. That memory can be hidden or inaccurate—it doesn’t matter. It’s there, isn’t it? It can be a lie but that lie becomes part of our memory, part of us». Conversazione tra Borges e il poeta e saggista argentino Osvaldo Ferrari, This is you here. «Così ora ho una grande quantità di stampe di prova. Forse una o due sono semplicemente favolose, e lo so. Bene. Le appendo tutte al muro con delle puntine in un posto con una buona luce e in una settimana circa si selezioneranno quasi da sole. Scoprirò come eliminare le più deboli e, fatto più importante, capirò meglio come guardo il mondo. Ancora una volta le fotografie sono la prova di un'esperienza e questa prova conduce a una nuova esperienza». Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018. «“Unreliable Narrator” plays on narrative interpretation and the existence of “truth” by placing differing versions of the same story together: my family’s, my own narrative, and the pervasiveness of memory through sequences of archive photography, text, my images, and my text. The project is designed to create assumptions of narrative and then works to undermine them […] is a reflexive interrogation of the stories that we tell each other, and ourselves. Using the personal archive as a starting point, I explore estranged relationships within my family and how trauma can continue to impact subsequent generations». Phil Hill, Unreliable Narrator. «Ma la passante è anche “in lutto”, non bisogna fare di lei un’opera d’arte, quanto piuttosto avvicinarsi alla sua vita, avvertirne la sofferenza, riconoscere in lei una finitudine: su questo piano ovviamente hanno luogo i veri incontri». Yves Bonnefoy, Poesia e fotografia. O Barra O Edizioni, 2015. «It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to». J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings. «Cultivation analysis asks, in other words, to what extent television “cultivates” our understanding of the world. […] One of the basic premises of Gerbner’s cultivation analysis is that television violence is not simple acts but rather “a complex social scenario of power and victimization”. What matters is not so much the raw fact that a violent act is committed but who does what to whom. Gerbner is as insistent about this as he is about anything, repeating it in all his writings and speeches. “What is the message of violence?” he asks me rhetorically over tea in his office at the University of Pennsylvania, a cozy, windowless rectangle filled with books, pictures, and objets d'art. “Who can get away with what against whom?”» Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997. «Chiunque riceve un’ informazione, specialmente se fotografica, deve chiedersi perché e in che forma sia utile a chi la trasmette; poi chiedersi ancora in che modo nuoce a chi la riceve». Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo. Mondadori, 2007. «In pointing to certain elements in ads, or movies, or fashion, I’m not ignoring the differences in how people may see things, but deliberately trying to direct your attention to what I see as significant. I’m making an argument, and you may or may not find it convincing. You might think - as my students sometimes do - that I’m “making too much” out of certain elements. Or your own background, values, “ways of seeing” may enable you to discern things that I do not. Or it may be that even as I offer my ideas, the cultural context has already begun to shift in ways that answer my interpretation or make it obsolete. Cultural interpretation is an ongoing, always incomplete process, and no one gets the final word». Susan Bordo, The Male Body. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2000. «We walk around with media-generated images of the world, using them to construct meaning about political and social issues. The lens through which we receive these images is not neutral but evinces the power and point of view of the political and economic elites who operate and focus it. And the special genius of this system is to make the whole process seem so normal and natural that the very art of social construction is invisible». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018. «Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation». George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976. «“What are the consequences of lifting bits of the culture of everyday life out of their context, repackaging them, and then marketing them back to people?” […] The alternative reality and culture that social media offer, distort people’s perception of reality, numbs critical viewpoints and only exposes users to likeminded individuals». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018. «What, Gerbner asks, does this cultivate in our kids, in society? “We live in a world that is erected by the stories we tell [...] and most of the stories are from television. These stories say this is how life works. These are the people who win; these are the people who lose; these are the kinds of people who are villains. It’s a highly stereotypic world day after day. It doesn’t matter whether it’s serious or humorous [...]. There is no more serious business for a culture or a society than the stories you tell your children.” [...] Of course, stories have always been used to teach and control [...]. What is new is that the stories are standardized and commercialized. “For the first time in human history,” Gerbner says, “the stories are told not by parents, not by the school, not by the church, not by the community or tribe and in some cases not even by the native country but by a relatively small and shrinking group of global conglomerates with something to sell. This changes in a very fundamental way the cultural environment into which our children are born, grow up, and become socialized.” It used to be that scary stories were told to children face-to-face, so they could be modulated, softened, individually tailored by the parents or the community depending on the situation and the desired lesson. Children today, in contrast, grow up in a cultural environment that is designed to the specifications of a marketing strategy». Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997. «I suppose unconsciously, or semiconsciously at bet, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women. The characters weren’t dummies; they weren’t just airhead actresses. They were women struggling with something, but I didn’t know what. The clothes make them seem a certain way, but then, you look at their expression, however slight it may be, and wonder if maybe “they” are not what the clothes are communicating. I wasn’t working with a raised “awareness”, but I definitely felt that the characters are questioning something – perhaps being forced into a certain role. At the same time, those roles are in film: the women aren’t being lifelike; they are acting. There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity». Cindy Sherman, Making of Untitled. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, Public Delivery, 2022. «Nel mito, la leggenda, la fiaba, il racconto, la novella, l’epica, la storia, la tragedia, il dramma, la commedia, il mimo, la pittura, nei mosaici, nei fumetti, nelle notizie, nella conversazione, in tutti i luoghi e in tutte le società. Indipendentemente da una suddivisione in buona e cattiva letteratura, la narrazione è internazionale, transtorica, transculturale: essa è semplicemente là, come la vita stessa». Roland Barthes, 1977. «La creazione narrativa della realtà non è sottoposta all’obbligo di dimostrazione formale, ma risponde al criterio della verosimiglianza. Agisce nel doppio scenario di azione (fare cose) e coscienza (osservare ciò che si fa e rifletterci su). Si interessa al particolare e al concreto, più che al generale e all’astratto, lasciandolo al pensiero paradigmatico logico-scientifico, interessato agli aspetti concettuali più universali e generali. Crea legami fra l’ordinario e lo straordinario, perché la storia inizia quando il protagonista varca la soglia per inoltrarsi nell’avventura straordinaria, e poi la varca di nuovo per tornare nel mondo ordinario. Secondo Bruner si tratta di uno dei meccanismi psicologici fondamentali per l’individuo e per i gruppi sociali e culturali […]. L’intelligenza narrativa è un’intelligenza ermeneutica, interpretativa. Si tratta di una capacità che va alla ricerca del significato di ciò che accade nella vita, della conoscenza di sé e degli altri, sia come singoli sia quale complesso inserito in un determinato assetto culturale». Bruner e il pensiero narrativo. Bibliografia Yves Bonnefoy, Poesia e fotografia. O Barra O Edizioni, 2015. Susan Bordo, The Male Body. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2000. Bruner e il pensiero narrativo. George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, primavera 1976. Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo. Mondadori, 2007. David G. Myers, Jean M. Twenge, Elena Marta e Maura Pozzi, Psicologia sociale. McGraw Hill Education, III edizione 2017. Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018. Niels Niessen, Shot on iPhone: Apple’s World Picture, 2021. Philip Perkis, Insegnare fotografia (Note raccolte). Skinnerbox, serie Skinnerbox Note, II edizione settembre 2018. Cindy Sherman, Making of Untitled. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, Public Delivery, 2022. Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin, 2004. Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings. Libri fotografici e Serie Roger Ballen, Asylum of the Birds. Albarrán Cabrera, This is you here. JR, Giants, Kikito, Border Mexico-USA, 2017. Phil Hill, Unreliable Narrator. Sally Mann, Proud Flesh. Pablo Rochat, Also Shot on iPhone, 2015. Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills. Giancarlo Shibayama, The Shibayamas. Iiu Susiraja, Lovely wife, 2018. Video Cindy Sherman, Nobody's Here But Me (1994). Fonte: Youtube.](https://makingpictures.ghost.io/content/images/2024/01/https-3a-2f-2fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984-s3-amazonaws-com-2fpublic-2fimages-2f5830772d-afc9-4469-b72b-24f6b710b156_1200x750-jpeg.jpg)

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.