#EN1.10 Stories we tell ourselves

If you don't keep your feet, there is no telling where you might be swept off to.

Every Making Pictures article originates from something I observe while reading or engaging in other activities. It could be a simple thought or a more complex idea that distracts me from my original task. Ideas are like mischievous sprites that appear unexpectedly. If I don’t take notes, they tend to disappear. Although I have a good memory, the more valuable the ideas are, the quicker they slip away.

I collect my notes in a notebook, which includes short sentences, quotes, videos, or pictures. I only jot down the bare minimum, leaving out any details or insights. I let it sit for a while and then I forget what I didn’t write down. What remains is a foundation for new ideas and creative connections. It’s like reading someone else’s notes, waiting to be developed.

One benefit of this approach is that when I forget why something is important, I can start the research process from scratch. However, this method can be unpredictable and frustrating as I may not know where the research will lead me.

«It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.» J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings.

Organizing my thoughts and putting them into words can be like going on a treasure hunt. It often leads me to explore areas that I would normally overlook and to gain a deeper understanding of the topic. However, there are times when I get caught up in complex arguments and slippery slopes.

For today’s article, I find this note:

“#1.10 George Gerbner”

Blank.

I am touched by the trust placed by my younger self, but girl I have no idea what you want me to write. This article is going to be an interesting adventure.

Let’s start with the facts: George Gerbner, a former Hungarian anti-fascist poet, emigrated to the United States. He later returned to Europe to fight during World War II under the USA flag.

After returning to the USA, he became a writer, a journalist, and a professor. Starting from the 1960s, he dedicated his entire life to studying the impact of media, especially television, on shaping and sometimes distorting the audience’s perception of reality.

«Cultivation analysis asks, in other words, to what extent television “cultivates” our understanding of the world.

[…] One of the basic premises of Gerbner’s cultivation analysis is that television violence is not simple acts but rather “a complex social scenario of power and victimization”. What matters is not so much the raw fact that a violent act is committed but who does what to whom. Gerbner is as insistent about this as he is about anything, repeating it in all his writings and speeches. “What is the message of violence?” he asks me rhetorically over tea in his office at the University of Pennsylvania, a cozy, windowless rectangle filled with books, pictures, and objets d'art. “Who can get away with what against whom?”» Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

Cultivation Theory has persisted through criticisms, expansions, and revisions, as it should. Over time, technologies advance, generations change, and only theories that are wrong or too limited remain unchanged.

Gerbner’s research isn’t just about establishing a simple cause-and-effect relationship between media violence and aggressive behavior. Instead, it focuses on power dynamics, asking “Who benefits, how, and at whose expense?”.

«Anyone who receives a piece of information, especially if it’s photographic, should ask why and in what form it’s useful to those who transmit it; then ask again how it harms those who receive it». Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo (Better to be a thief than a photographer). Mondadori, 2007.

Why am I seeing this? What do you want to tell me or, rather, what is left for me or what is taken away from this exchange?

This perspective applies to images but in general to all information around us. Perhaps the word “harm” seems too strong because we generally feel stable and centered enough not to perceive threats from information. Instead, we can be much more vulnerable than we think, either because of characteristics such as age, for example (children or teenagers, but also any age group where we experience changes), or because of situations that make our mental immune system1 much weaker. Sudden negative events, instability, and uncertainty about the future. Can you think of any?

«In pointing to certain elements in ads, or movies, or fashion, I’m not ignoring the differences in how people may see things, but deliberately trying to direct your attention to what I see as significant. I’m making an argument, and you may or may not find it convincing. You might think - as my students sometimes do - that I’m “making too much” out of certain elements. Or your own background, values, “ways of seeing” may enable you to discern things that I do not. Or it may be that even as I offer my ideas, the cultural context has already begun to shift in ways that answer my interpretation or make it obsolete. Cultural interpretation is an ongoing, always incomplete process, and no one gets the final word» Susan Bordo, The Male Body. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2000.

Representation in media is a fascinating aspect of Cultivation Theory, as well as a slippery slope argument. It’s a major issue that cuts across various aspects, and to be honest, my knowledge is quite limited. I try to approach it with an open mind, a critical eye, and a compassionate heart. But, at times, it takes a conscious effort to maintain this perspective, as it seems more natural to go with the flow.

«We walk around with media-generated images of the world, using them to construct meaning about political and social issues. The lens through which we receive these images is not neutral but evinces the power and point of view of the political and economic elites who operate and focus it. And the special genius of this system is to make the whole process seem so normal and natural that the very art of social construction is invisible». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

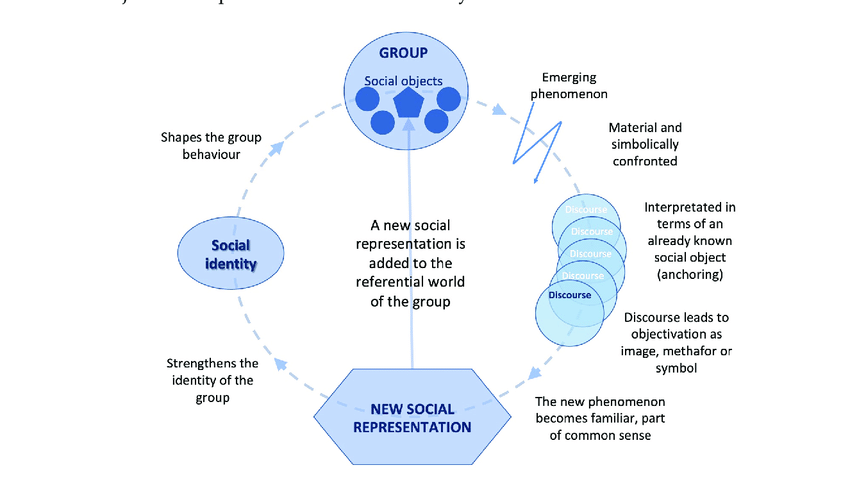

In the earlier posts, we discussed the concept of schemas and how they evolve with time, influencing our thoughts and actions. Social representations in the form of patterns and structures, are also present in our societies, as actual objects that belong to a certain group and characterize it. Some constructions are opaque and easily recognizable but others are transparent and sometimes more dangerous.

Social representations are pathways of reasoning, judgment, and action that become automatic, leading individuals from point A to point B without much thought. They are often accepted at face value because they are deeply ingrained in our culture. For example, the phrase “boys will be boys” is a common phrase that can excuse harmful behavior. While social representations can be useful and save mental resources, they can also be harmful by creating a narrow worldview that limits our understanding of other realities. In such cases, it’s important to question them and create situations that challenge and confront them, leading to the creation of new and appropriate representations.

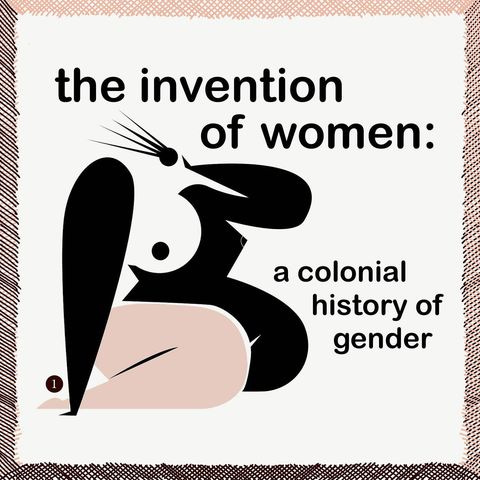

When a society completely excludes certain individuals or entire groups from the media, from everyday conversation, and from culture in general, it symbolically annihilates them.

«Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation». George Gerbner e Larry Gross, Living With Television: The Violence Profile. The Annenberg School of Communications, Journal of Communication, vol. 262, Spring 1976.

In a nutshell, it means that within that society (but it also applies to smaller groups) those individuals are stereotyped and treated accordingly, ignoring needs, legacies, and identities. This causes problems that often hide behind good intentions but ultimately fail to achieve their purpose.

It’s often assumed that pop culture, including music, movies, video games, comics, and trends, is not capable of delivering meaningful messages. Compared to “high” culture, which is considered to be more significant, pop culture is often overlooked. While “high” culture does play a role in shaping society, pop culture is more accessible and prevalent. We are exposed to pop culture daily, without even realizing it. Our routines have a more lasting impact than the occasional indulgence in something like pandoro with mascarpone.

About media and pop culture, I can’t demonize their influence on my perception, reasoning, and understanding of the world. Rather than limiting my perspective, they have broadened it. Fortunately, they continue to do so.

A post shared by @alokvmenon

Through these media, I have gained immense value that I use to my advantage as an active user, not just a passive consumer of content. This is particularly important to me because I was born and raised in a small provincial community before the Internet era. Without these channels, I would have never been able to connect with certain realities and learn as much as I have.

On the other hand, I recognize social media’s limitations and distorted dynamics. It promotes content according to algorithms and likes, often highlighting extreme points of view. Sometimes these spaces make me uncomfortable.

«“What are the consequences of lifting bits of the culture of everyday life out of their context, repackaging them, and then marketing them back to people?” […] The alternative reality and culture that social media offer, distort people’s perception of reality, numbs critical viewpoints and only exposes users to likeminded individuals». Raziye Nevzat, Reviving Cultivation Theory for Social Media. The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, 2018.

Social media companies need profits, although sometimes it’s easy to forget that.

In addition to members’ data, social platforms generate revenue through advertising. Many influencers act as human advertising space for companies, leveraging the persuasive power of “two-step” communication.

Social platforms serve as tools for selling products, services, and ideologies. But people use them to seek opportunities for entertainment, social interaction, and information too.

«What, Gerbner asks, does this cultivate in our kids, in society? “We live in a world that is erected by the stories we tell [...] and most of the stories are from television. These stories say this is how life works. These are the people who win; these are the people who lose; these are the kinds of people who are villains. It’s a highly stereotypic world day after day. It doesn’t matter whether it’s serious or humorous [...]. There is no more serious business for a culture or a society than the stories you tell your children.”

[...]

Of course, stories have always been used to teach and control [...]. What is new is that the stories are standardized and commercialized. “For the first time in human history,” Gerbner says, “the stories are told not by parents, not by the school, not by the church, not by the community or tribe and in some cases not even by the native country but by a relatively small and shrinking group of global conglomerates with something to sell. This changes in a very fundamental way the cultural environment into which our children are born, grow up, and become socialized.” It used to be that scary stories were told to children face-to-face, so they could be modulated, softened, individually tailored by the parents or the community depending on the situation and the desired lesson. Children today, in contrast, grow up in a cultural environment that is designed to the specifications of a marketing strategy». Scott Stossel, The Man Who Counts the Killings. The Atlantic, maggio 1997.

Every once in a while, I come across posts like this one that make me think.

This article talks about the emergence of “a more truthful and authentic language” in social media. But I can’t quite believe it, mainly for two reasons.

The first concern is related to the commercial vocation of social media. I’m glad to see the decline of the hyper-perfect, overly-retouched model of visual communication. However, the overlapping of communication codes (persuasive and informative) often leaves me confused. Perhaps it’s an attempt to enhance customer loyalty rather than direct sales, but it can make it difficult for me to discern the true nature of what I’m seeing. Is it a true story? Is it fiction? Is it advertising? Companies often prioritize their interests over those of their customers in this type of code juggling.

Secondly, the “triumph of sincerity” implies that there cannot be multiple public personas. It assumes that what we see on social media is an authentic representation of a person’s life and not just one of their many roles, which could have been adopted voluntarily or forced by context or other factors.

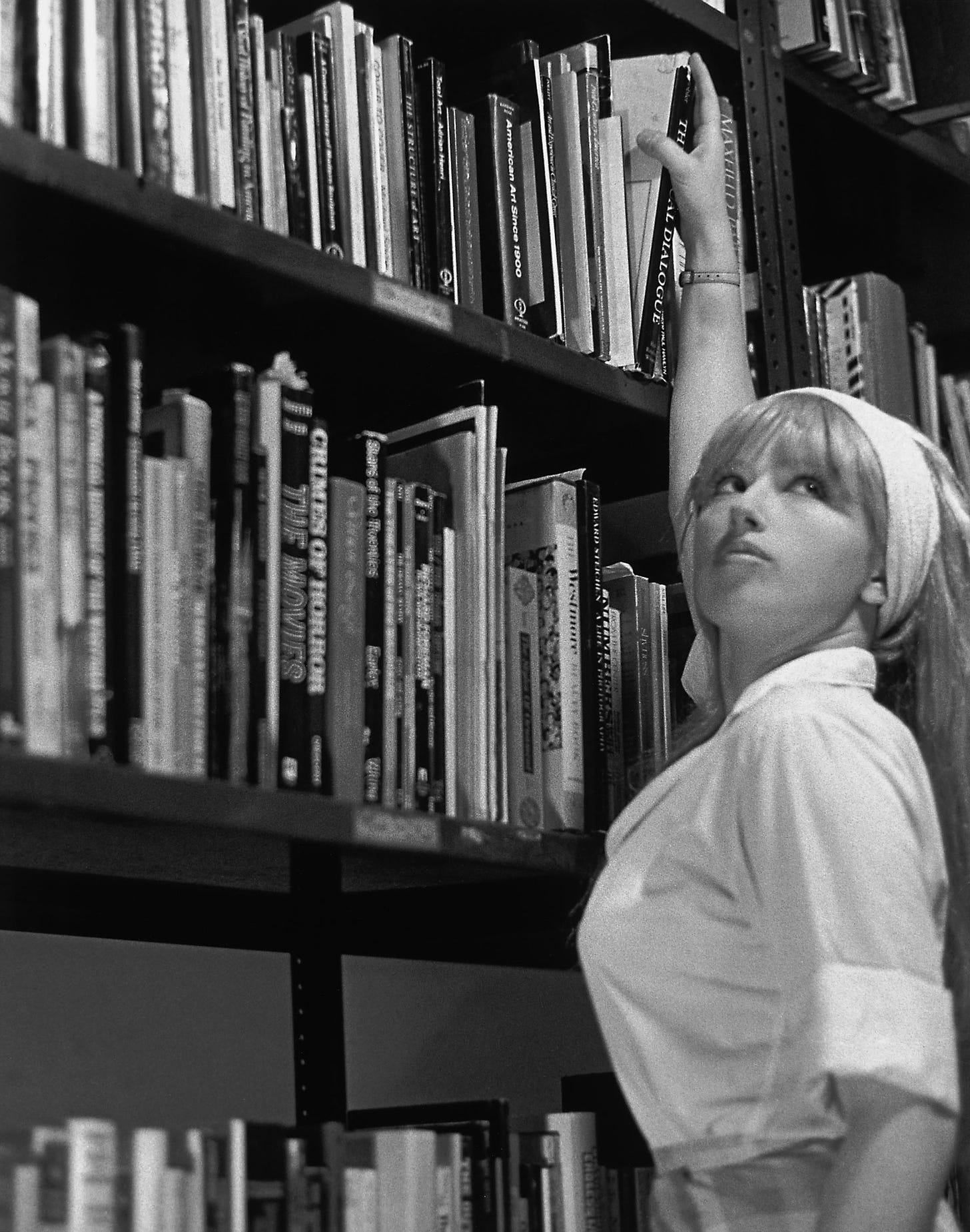

«I suppose unconsciously, or semiconsciously at bet, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women. The characters weren’t dummies; they weren’t just airhead actresses. They were women struggling with something, but I didn’t know what. The clothes make them seem a certain way, but then, you look at their expression, however slight it may be, and wonder if maybe “they” are not what the clothes are communicating. I wasn’t working with a raised “awareness”, but I definitely felt that the characters are questioning something – perhaps being forced into a certain role. At the same time, those roles are in film: the women aren’t being lifelike; they are acting. There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity». Cindy Sherman, Making of Untitled. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, Public Delivery, 2022.

While writing this article, I came across a 1994 documentary about Cindy Sherman’s work that I had never seen before. I found it to be particularly interesting because Sherman speaks candidly and frankly about her journey into photography. She delves into how her life experiences, unconscious intuitions, intentions, skills, and chance have all contributed to her art.

Cindy Sherman aimed to construct characters in a way that lets the viewer imagine their own story.

«Narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting […] stained-glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation. Moreover, under this almost infinite diversity of forms, narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society; it begins with the very history of mankind and there nowhere is nor has been a people without narrative.

[…] Caring nothing for the division between good and bad literature, narrative is international, transhistorical, transcultural: it is simply there, like life itself.”». Roland Barthes, 1977.

Narrative thinking extends beyond books, movies, or entertainment. Its purpose is to assign meaning to our experiences. Photography, such as that of Cindy Sherman, is one of the instruments that we employ to achieve this end. We may use it to attribute significance exclusively to ourselves, through personal projects seeking what’s essential for us, or to show something to others. At times, these routes are distinct, while at others, they coincide.

«The narrative creation of reality is not subject to the obligation of formal demonstration but meets the criterion of verisimilitude. It acts in the dual scenario of action (doing things) and consciousness (observing what is done and reflecting on it). It is interested in the particular and the concrete, rather than the general and the abstract, leaving it to logical-scientific paradigmatic thinking, which is interested in the more universal and general conceptual aspects. It creates links between the ordinary and the extraordinary, because the story begins when the protagonist crosses the threshold into the extraordinary adventure, and then crosses it again to return to the ordinary world. According to Bruner, this is one of the fundamental psychological mechanisms for the individual and for social and cultural groups [...]. Narrative intelligence is a hermeneutic, interpretive intelligence. It’s a capacity that goes in search of the meaning of what happens in life, of knowledge of self and others, both as individuals and as a complex embedded in a given cultural arrangement». Bruner and Narrative Thinking.

William J. McGuire’s Inoculation Theory uses the analogy of the immune system and vaccines to explain and demonstrate how beliefs and attitudes can be protected from aggressive persuasive messages.