#EN1.11 Photography is a language

But - what is a language?

When I was six years old, I took two photos at the seaside. I still remember the camera, the pictures, the place, and the time.

Episodic memory is a part of our long-term memory that stores the engrams, the traces of events we experience or witness throughout our lives. It is one of the components that define our identity and is strongly linked to emotions and the oldest parts of our brain. We tend to remember emotionally significant events better than others, except when the feeling is too intense. In such cases, stress triggers the production of hormones that inhibit the hippocampus, and no further memory is formed. This is a natural defense mechanism.

During the first few years of my photography journey, I took pictures just for the joy of capturing them. Many people pursue photography as a means of self-expression, and I too would have said the same if asked. When we don’t know how to define our feelings or actions, we usually resort to the most common answer, which is quite normal.

Looking back at that time, I realize that I was in an “image-consumer” phase. I would devour them every day from books, television, reality, and the Internet. Pinterest and Instagram did not exist then, so I downloaded, printed, and saved them in folders. I was also taking lots of pictures, but primarily for personal use rather than to show them to the world. Practicing photography made me feel good, and feeling good motivated me to practice more.

Just like how children take years to learn the language of adults, initially, they explore and experiment with all the possibilities of articulation, expression, and comprehension. During the first few months, there is no real communicative intent, and some expressions are just for practice to understand their social environment’s response and acquire vocabulary and structure. In any language, comprehension always precedes production.

«ALEXIS DAHAN —What is the difference between a skilled photographer and everybody with a telephone?

STEPHEN SHORE — I think it is a number of things. It is the intention because framework is part of the intention. But it is also the understanding of visual grammar. Let’s compare it with verbal language. You can take a picture that is in focus, well exposed, with content, a picture plane, and four edges, but even my cat can do this! And I mean that literally. Formally, it’s a complete photograph, even though it has been made without any sense of visual grammar or visual structure. On the other hand, while a photograph can be made without any sense of structure, in order to produce language you need a basic understanding of the structure of language». Alexis Dahan, Stephen Shore On photography Vs Instagram. Purple Magazine, 2015.

To write a shopping list, I don’t need to know much vocabulary. I don’t need to worry about morphology and syntax. However, writing a poem requires a different set of skills. Broader, maybe?

A post shared by @found_zine

I don’t want to go off-topic, but I’m pondering about something quite intriguing, and I haven’t found a definitive answer yet. According to some linguistics textbooks, poetry demands the highest awareness of a language’s structures and potential. However, some linguistics textbooks tend to prioritize conscious thought and reason while disregarding the communicative and affective domains. Although reason can (somehow) describe emotions, how can it explain what it means “to feel”?

«Sign languages that also make use of the simultaneous dimension can convey multiple data simultaneously. The possibility of gesture to have a more direct and immediate relationship with sensible representations [...] also allows us to better understand the relationship between the senses and different forms of representation, such as artistic ones: poetry, painting, sculpture.

[...] the senses come into play in the constitution of human experience and, in particular, of aesthetic experience». T. Russo Cadorna and V. Volterra, The sign languages: history and semiotics (Le lingue dei segni: storia e semiotica). Carocci publisher, 2021.

Language in my opinion (for the time being) is more dependent on a degree of “immersion” rather than “learning”. The ability to speak, or write, a language is only a small part of the overall language experience.

In living organisms, language is an instinctive ability that is triggered by context. Photography can also be considered as a form of language.

«Photos are taken everywhere in the world, and people spend their lives seeing photos every day. I’ve come to think that photography has a nature not unlike language and that it has different dialects too. The way photos are taken, and the way they are viewed, is affected by both geography and history. There are a lot of traditions mixed in too. I think my photos belong to an American dialect. When I started taking photos and chasing after my style, the Internet hadn’t evolved to what it is now. So I was totally immersed in the American tradition. That meant it was quite ordinary that I would be looking at the photos of famous American photographers like Robert Adams or Stephen Shore. This couldn’t help but have an effect on my own viewpoint and photography technique». Alec Soth, Intervista New Cosmos of Photography.

A few years ago I was feeling disgruntled about photography and thought that I had exhausted all the options. I felt the lack of references and I remember that feeling very well. I felt without alternatives and forced into a very narrow niche of photography that was not for me. Nowadays, it seems much easier to access different perspectives, but I am not sure how much of that is a fact, or I am just more “trained to see”, or both.

At some point, I started trying everything I could. I remember a little book from 2009 that would make people smile today (it would probably be an Instagram account), but which was very useful to me at the time. It was so different from all the other “serious” photography books.

When I first started working with photography, I had to interact with people who had more skills and experience than me (well, this still happens today!). I couldn’t just lock myself in a bubble thinking that I was doing it for myself. By the time I got a VAT number, I realized that I was serious about photography and wanted to do my best without any second thoughts.

I also learned that photography is a language, broadening my perspective in many ways. We all know what a language is, and photography goes beyond just capturing what we see to a tool for expressing and telling something.

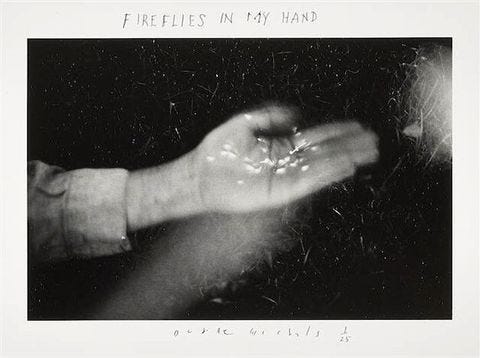

For a long time, in my head, photographic language has been somehow associated with verbal language. However, I soon realized that images and words have different characteristics, and it is not always necessary to translate them one way or the other. Sometimes they can be equivalent, sometimes they can create additional links, and sometimes they can reinforce each other.

A post shared by @duanemichalsduanemichals

A post shared by @duanemichals

When it comes to creating images, it’s not just about putting elements together, sequencing, intentionality, conveying meaning, and so on. As if the purpose of images were only to explain, document, express, and inform, always with underlying concepts. As if we could read images as we analyze text, breaking it down into their minimal elements, which we can do. However, this approach has many limitations. It prioritizes cognitive faculties over instinct and feelings as if they were raw materials to be scrutinized to create a “valid discourse”.

Photography is a language. It is true. But what is language?

«What does it mean to be literate in photography? Superficially, it might suggest an ability to “read” a photograph, to analyse its form and meanings. But what about the making of photographs? We would argue that literacy is more than just a command of the mechanics of a particular “language”. It also takes into account fluency of expression and sensitivity to material». Photopedagogy, What is Photo Literacy?

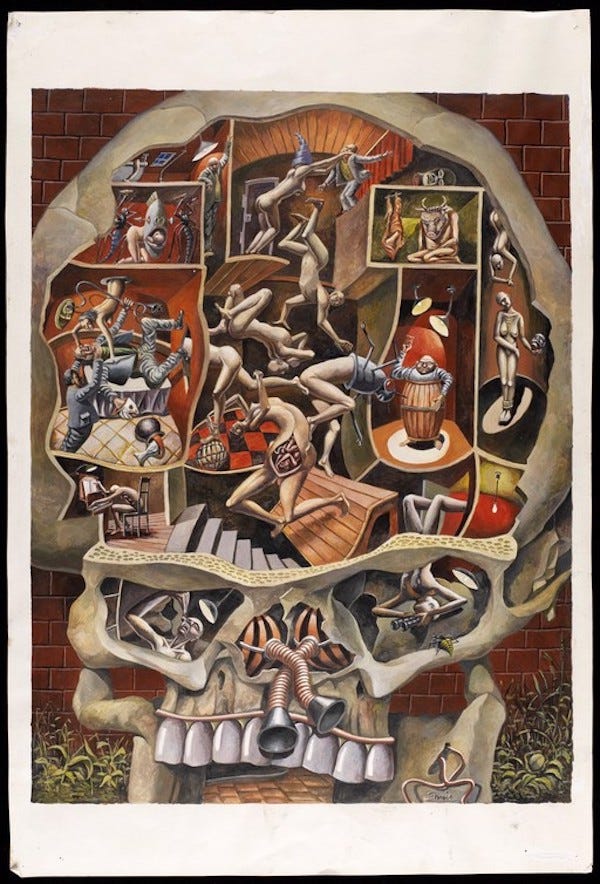

Discussing language is akin to unlocking a Pandora’s box, unleashing a herd of evolving knowledge, models, and theories. Language is a multifaceted, intricate, dynamic, multimodal, and multifactorial faculty. It is studied from various perspectives, analyzing diverse domains such as comprehension, expression, articulation, and motor function, in addition to the areas concerning the verbal and semantic sphere.

«Language (or, rather, “faculty of language”) is the prerequisite for languages; it represents the “support” on which languages are then “installed”. Language is usually defined as a human faculty to create systems of communication by matching content and means of expression. It is part of the innate endowment that every member of the species possesses at the moment of coming into the world, in much the same way as the liver, nose, feet, etc.

[...]

Language does not have a clear and unique location in our organism (unlike, for example, the digestive or respiratory system), but seems to “distribute itself” within it (involving, for example, the brain, lungs, oral cavity, nose - for verbal languages - arms and hands - for sign languages - etc.). Little can we say about the genes that regulate our language abilities (except that the search for a phantom language gene soon turned out to be a chimera)». Linguisticamente.org, Parliamo una lingua o un linguaggio?, da F. Masini e N. Grandi Tutto ciò che hai sempre voluto sapere sul linguaggio e sulle lingue. Bologna, Caissa Italia , 2017.

While practical experience is crucial, language serves as a neutral medium and the primary tool for understanding and describing one’s photography. This makes sense, as language is the primary means of exchanging ideas, formulating thoughts, and communicating our internal and external realities to others.

However, this approach often reinforces the idea that lacking the ability to express oneself through language is equivalent to not possessing knowledge or awareness. This can be frustrating, especially if we feel strongly about something in our bodies, emotions, attitudes, and actions, but cannot articulate it in words.

There are so many things that cannot be explained through words. We simply feel them.

«When I photograph, I am trying to grasp the “whole”. This requires me to trust my instinct and impulse of the moment. I cannot do it with thinking alone». Philip Perkis, Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. Kindle Edition.

I KNOW.

I understand the dangers of this statement in photography. Some take refuge behind “that’s how I feel and I like it that way”, relying on “talent” and “instinct”. Some people use the camera using their emotions to justify everything. Emotions can be a baffling subject for many people on this planet.

«In his essay The Human Universe, Charles Olson postulates that since the Greeks, our system of language has become more and more about description of intellect and concept and has lost its ability to express experience directly. [...]. something. Photography provides a window through which we can see things that we fear or do not want to have contact with directly. It’s not just about seeing things that are not available or no longer exist such as Abraham Lincoln or the Hindenberg». Philip Perkis, Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. Kindle Edition.

«A widely held notion about pain seems to be that it “destroys language”. But pain doesn’t destroy language: it changes it. What is difficult is not impossible. That English lacks an adequate lexicon for all that hurts doesn’t mean it always will, just that the poets and marketplaces that have invented our dictionaries have not—when it comes to suffering—done the necessary work». Anne Boyer, The Undying. Kindle Edition, 2020.

Language is a complex system that involves the affective, cognitive, and motor domains. The ability to express oneself is connected to all these domains, and nurturing them has a significant impact on language (and photography).

«Photo Literacy is therefore a specific type of understanding that combines visual, linguistic, emotional and physical acuity». Leslie Owen Wilson, Understanding the Revised Version of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

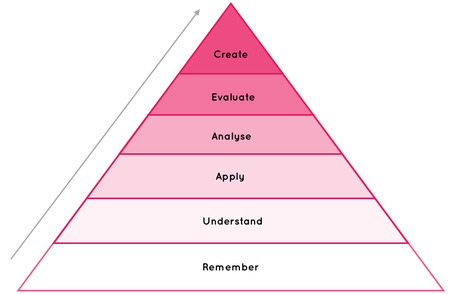

The cognitive domain is dominant not only in photography but also in other fields of study. Lots of models, theories, and tools of analysis are focused on this domain. However, tools and methods are products of society and culture, never completely objective. This makes sense in a world where reason and performance are highly regarded.

In my experience, photography is a delicate balance between knowledge and “personality”. Some photographers focus solely on mastering techniques and equipment, yet they end up taking only a few pictures that are equivalent to a grammar exercise in fine print. On the other hand, some photographers rely on their intuition and their own emotional world as well as paying attention to external stimuli. They create images that are loaded with content but are sometimes at the mercy of the storm, lacking technical awareness and compositional skills that could have made their images more effective and powerful.

«The minute you start saying something, “Ah, how beautiful! We must photograph it!” you are already close to the view of the person who thinks that everything that is not photographed is lost, as if it had never existed, and that therefore, in order really to live, you must photograph as much as you can, and to photograph as much as you can you must either live in the most photographable way possible, or else consider photographable every moment of your life. The first course leads to stupidity; the second to madness». Italo Calvino, The adventure of a photographer.

Making photographs involves thought, emotion, and body. There is a wonderful site where I often clear my mind: photopedagogy.com.

In photography, the cognitive domain includes thinking, understanding, reasoning, and so on. Rules, technical notions, and knowledge. This is true both when we look at images and, especially, when we produce them. Understanding a language is the basis of production.

It all starts with the act of seeing and looking at something. Then it is remembering, understanding (what am I looking at?), and applying (what are the formal elements? What is the light like? What medium was it taken with? Where is the focus?).

Analyzing is the next step after applying. It’s the process of putting our own thoughts and knowledge into the analysis. We need to consider what strikes us the most, and what we know about the context behind the photograph. Analyzing is about clarifying what we see.

Evaluating is the process of deciding what works and what doesn’t work in the photograph. This helps us to make decisions about how to proceed. But it’s important to note that while models may provide an ideal structure, our evaluations are often influenced by our emotional response to the image. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it can be problematic when our emotional response is passed off as fact. We need to take a moment to assess our emotional response and decide which direction to take.

Creating is the final step in the process. It’s the act of making photographs in response to underlying stimuli and processes. It’s like language that is activated by the context around us. Without this interaction, we would have nothing to say.

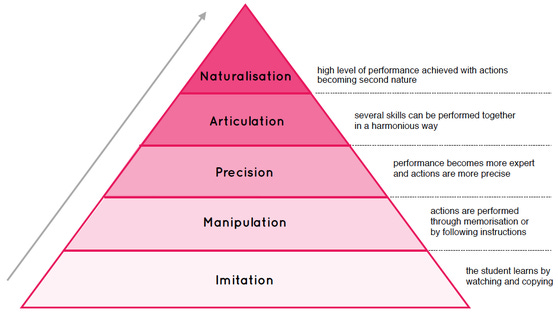

Let’s talk about the psychomotor domain. Photography is a physical practice, our bodies are tools that we use to make photographs. We need to consider our eyes, legs, back, and joints when taking photographs. While physical strength may be required for some situations, it’s not the only aspect of the psychomotor domain.

When we take photographs, we need to coordinate a range of movements and information from our eyes to the brain and muscles. The more we repeat these movements, the more they become procedures or reflexes that require little effort.

However, there are still photographers who have little care for their physical and mental well-being. I’m not suggesting that they should be like athletes, but there are many who push themselves to their limits, almost as if they’re trying to show off. This is a problem that needs to be addressed.

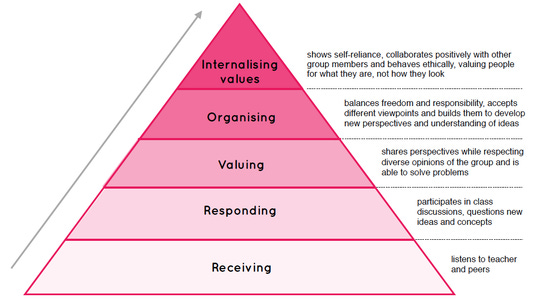

Lastly, the affective domain. It’s not just about what we enjoy or don’t enjoy, but it also involves our values, experiences, and motivations related to photography. Emotions are also influenced by our social interactions, how we deal with problems and frustration, and how we interact with our subjects.

How should I interact with the people who collaborate with me? How do I decide which subjects to photograph? At the end of the day, what matters most to me?

In the realm of emotions, it’s difficult to be honest and truthful, even with ourselves. One part of us tends to conform to social norms and expectations, while another part wants to be free to act on our own. Each person has their own balance point, which changes over time as we internalize values and patterns from our environment. Sometimes, these models are based on role models we admire in photography (and beyond).

Mastering this domain, like any other, takes practice and learning to recognize our emotional responses in different situations. It involves exploring our feelings without judgment, and with patience. It’s a complex space, but with time and effort, we can learn to navigate it effectively.

«No rudeness. No competition. No telling the artist what the work means about them (a critique is not psychotherapy) […]. They can report associations in their minds, dreams and fantasies as long as it’s about the work and not about the person who made the work». Philip Perkis, Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. Kindle Edition.

Out of the three areas in photography, the affective-emotional aspect is where I struggle the most. It’s difficult (if not impossible) to accurately interpret the feelings of others, and even when it comes to our own emotions, it’s not always a simple task.

I approach photography by asking a lot of questions, which helps me discover new things. However, sometimes my interpretations can become a bit heavy. Photography is a complex language, so maybe it’s just a matter of adding a little bit of levity to it as well.

«After writing fiction for forty years and exploring various paths and experiments, I feel it’s time to define my work. Simply put, my goal has been to subtract weight. I’ve aimed to take away weight from human figures, celestial bodies, and cities, but most importantly, from the structure of the story and language itself». Italo Calvino, Lezioni Americane. Sei proposte per il prossimo millennio (Six Memos for the Next Millennium). Mondadori, 2016.