#EN1.2 A mind full of schemas

The enigma of the photographer’s voice.

Hello, we’re off to a serious start today!

It’s the first “real” Making Pictures article. If you’ve subscribed to the newsletter, you’ll receive posts via email (and Substack App, if you’d like) on the last Wednesday of each month. You can also read everything like a blog (no subscription needed). It’s up to you :)

With Making Pictures, we’ll explore the human within the photographic process. What leads us to create some photographs instead of others? What happens when we relate to images? What makes us unique as photographers? It’s a topic with few fixed stakes and many open questions. We can approach each issue from several valid points of view.

Before I begin, thank you for reading and subscribing: your trust means a lot to me. I’m working hard to dissect and explore each topic to the best of my ability. Still, if you have any doubts or questions, you can contact me by email (info@florianariccio.com). I will be happy to discuss them.

The photographic voice: a fascinating and complex issue. Frustrating, sometimes. We can understand it, but only up to a point. It’s one of those features that seems more evident to those who observe us from the outside than ourselves.

It’s not easy to write about it without belittling the subject. Thoughts in the head leap from one side to the other, making associations that would be perfect in poetry, music, or dance. A tremendous in-person chat over a beer, maybe, so the concept comes through tone of voice, pauses, and body language, not only words. Words have limits.

Children in some cultures learn nouns earlier, in more significant numbers, and much faster than verbs, while in others, the opposite happens. The language of the former is based on categories, while that of the latter gives more importance to relationships1.

Language development is related to thinking, which creates meaning and our experience of the whole world. Mind developing in individualistic societies (Europe and Anglo-Saxon countries, for example) organizes in categories, defines rules, and looks for cause-and-effect relationships. Reason breaks down objects and events deterministically, analyzes them, and makes them predictable.

In the Bible, in the translation of Genesis that I’ve learned as a child, Adam, man #1, first gives a name to all creation in Eden2. Categories and reason are impressed in our neural circuits. They are powerful constructs, even in communication.

Early psychologists quickly realized that something in the human mind could be recorded, measured, and studied, and something else could not. We are in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century. Still, this awareness has been rooted in philosophy, science, and religion for centuries. Body and mind, matter and soul, these pairs are found just about everywhere. When I think of photography: form and substance, container and content, technique and creativity.

I’ve learned that images also live from this tension. Photographers gravitate around these two poles, drawn a little to one, then to the other. It isn’t true for everyone and every time, of course. I see this in those who still need to find a balance. Or temporarily don’t have one. Not because they’ve lost it who knows how, but because they’re asking questions and exploring beyond their capabilities. Growing up is a delicate process and requires a lot of energy. One can feel lost. It happens.

Some images are perfect but soulless, while other photographs scream out, blowing any rule to smithereens. Often the last ones seem the most interesting because one of the ideas of “art” in our heads is something intense and incomprehensible that grabs at the stomach. As photographers, we get up every day hoping to create something powerful, but there are different ways to do it. Sending out images that hit anyone like a fist, without discrimination, is dangerous.

We can study and practice techniques. But what about talent? Style? One’s uniqueness?

It becomes increasingly difficult for me to hold the reins of this discourse. But before I let it run free, I’d like to reiterate some points.

- Talent is not innate nor a divine gift. It results from an infinite number of factors interacting with each other over time.

- Voice isn’t immutable. It’s dynamic, varying with practice. Growth and learning are not linear and cumulative processes: they’re winding paths that sometimes even force one to go back and retrace steps.

«[...] magicians, astrologers, alchemists, with their imposing mass of experiments, behave like ants, accumulating so many things without any discernment or elaboration; but, conversely, Aristotelian doctors, still present and dominant in universities, behave like spiders, who weave webs, even wonderful ones, the result of their slime only, without any relation to what is happening in the world. Instead, the true philosopher, the scientist in the modern sense of the term, must be like the bee, who takes nectar from the outside, but personally reworking it transforms it into honey.» Paolo Legrenzi, Storia della psicologia (History of Psychology). Il Mulino, 2012.

Our mind doesn’t accept this willingly: with pain comes gain, and with practice, improvement3. Given A, then B. Reason and logic first. It’s true. But these tools are as good for training one’s photographic voice as a screwdriver is for hammering in a nail. One may even succeed in the end, but the whole process becomes longer and far more frustrating. Letting go of the reins of the reason is scary. But the soul needs to breathe to explore the unknown space.

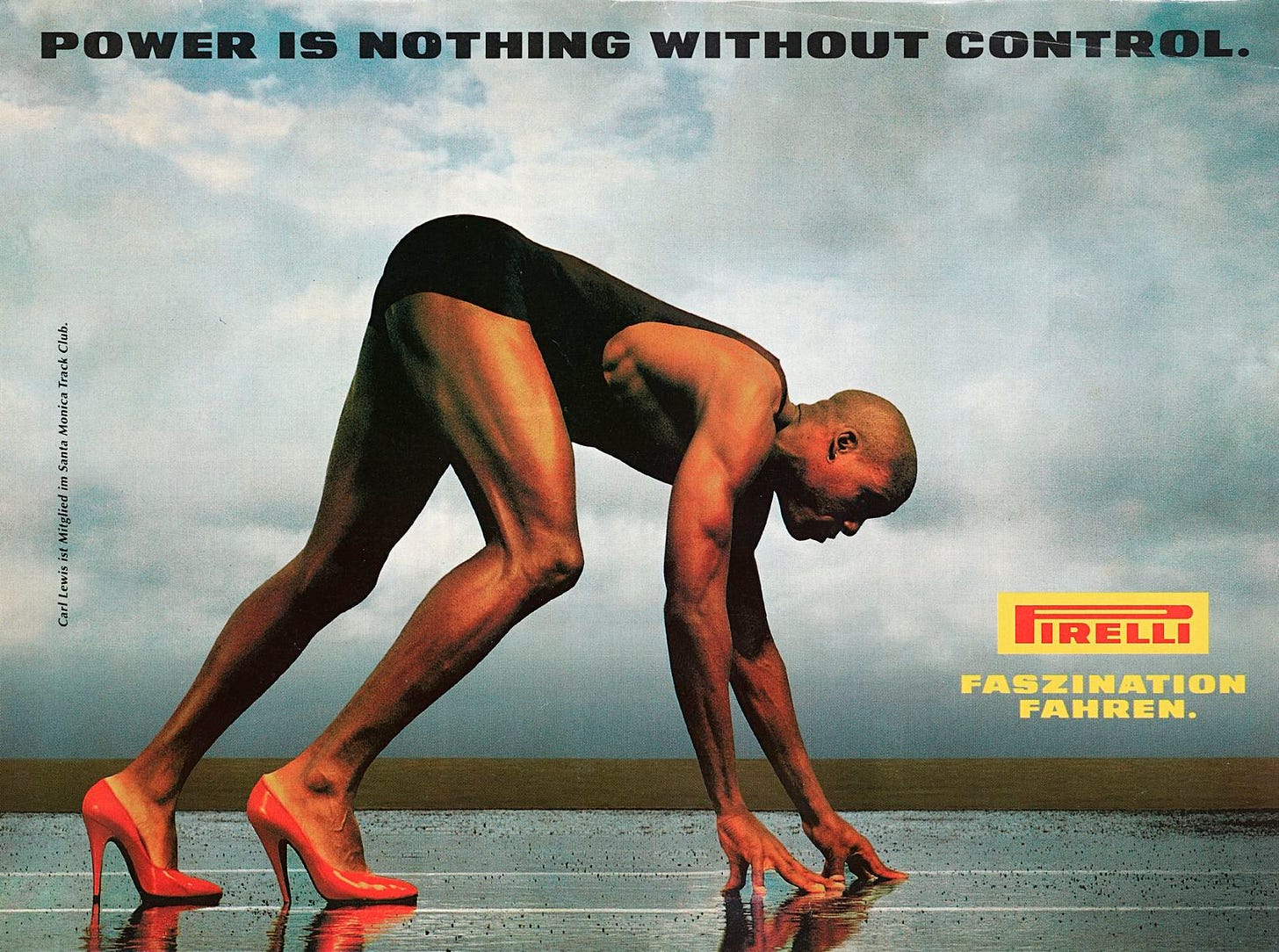

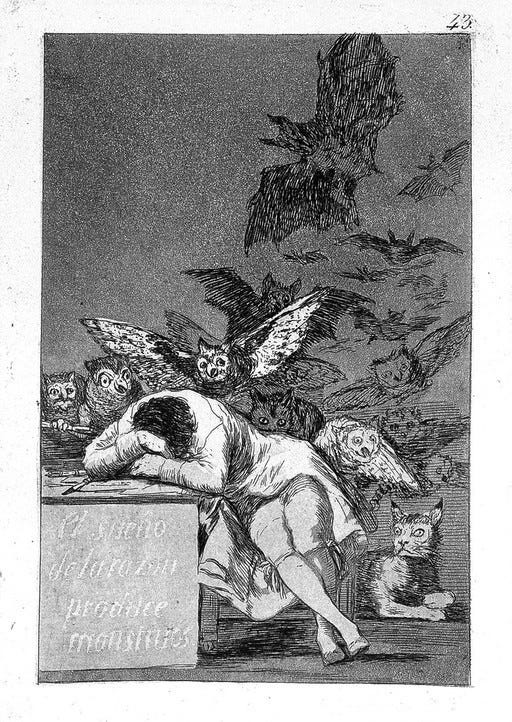

According to the European Enlightenment tradition, the absence of reason leads to danger and evil. A manuscript attributed to Goya4 gives a less rigid interpretation: “When abandoned by Reason, Imagination produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their wonders.” A collaboration between reason and the unconscious, where the latter, however, always needs levees. Power is nothing without control. Here we are again.

Some cultures see monsters and spirits as neither good nor bad. We share the same world. They can cross our paths.

«Unlike Judeo-Christian places of worship, Shinto shrines are not places where the spirit of the holy might be captured, harnessed, ordained, and instrumentalized. Instead, he maintains that shrines are places of possibility - spaces where the spirits that inhabit all aspects of the world might visit and rest, and where humans might offer their best wishes, hopes and dreams. In that way, they become repositories of possibility. They offer no promises». Ian Lynam, The Impossibility of Silence: Writing for Designers, Artists & Photographers. Onomatopoeias, 2020.

No expectations, only possibilities. Shatter the illusion of control over the world, events, and even ourselves. The best photographs arise when we “dance” with the subject in front of us. We open our eyes to all the possibilities instead of forcing the direction we have in mind.

Reason puts reins in our hands and deludes us into thinking that the horse only ever goes where we want it to go. And when we find ourselves in a place that works, that we like, we convince ourselves that we have consciously taken all the proper steps to get there.

«Until the day photography was discovered and the ascent began. Because it soon took as much strength and culture for the photographer to make one as it takes to ring a doorbell. Then someone comes to open it for us, or better yet, an image of it, and we think, with some reason, that we precisely created it». Ando Gilardi, Meglio ladro che fotografo (Better Thief than Photographer). Bruno Mondadori, 2007.

We are entering a bubble of uncertainty, a space in which we are not in control. Automatic processes drive our lives a lot.

Some processes regulate essential physiological functions. Without those, we wouldn’t be here talking about them. And then we can talk about hyper-learned routines, such as driving a car and photographing without thinking about where you adjust what. There is even a memory dedicated to these routines. But the most exciting fact is that automatic processes also guide perceptions, feelings, thoughts, intentions, choices, and behaviors. Awareness is rooted in the unconscious. The logic of thinking does not coincide with formal logic. Human reason, after all, is not 100% rational. It’s all so magnificent and human.

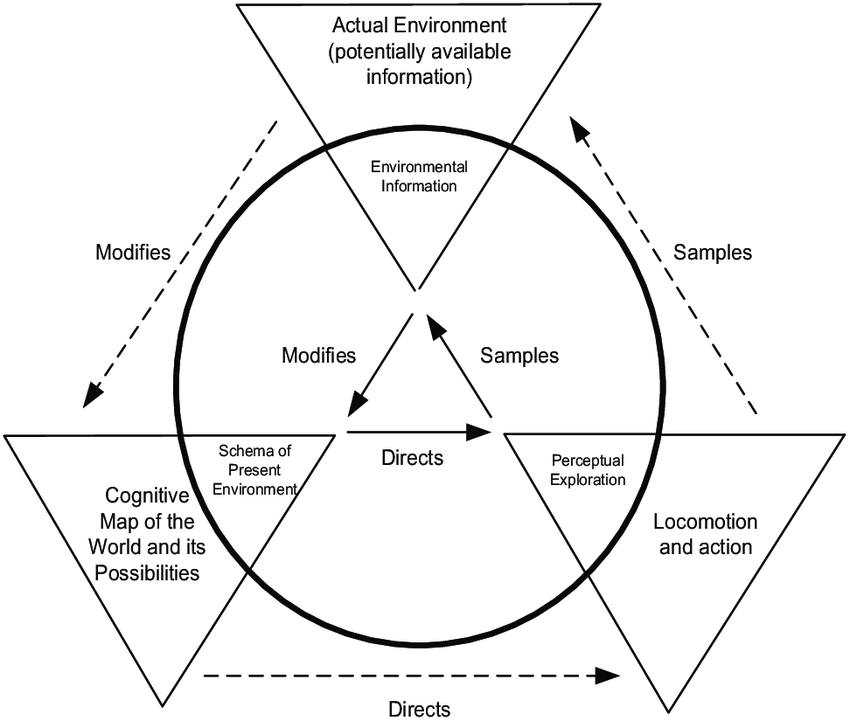

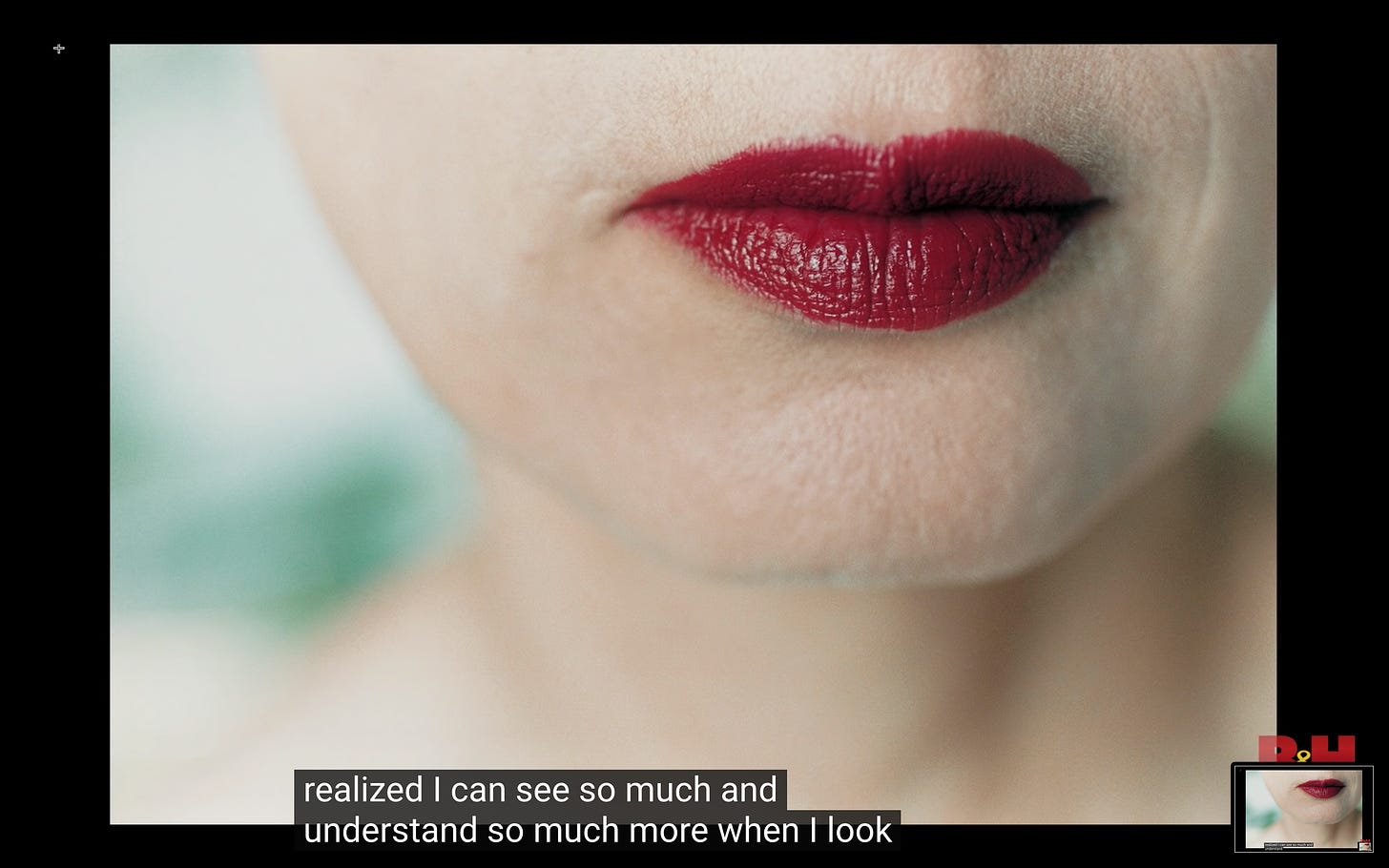

Automatic processes are unintentional, unconscious, uncontrollable, and efficient. They guide how we select and respond to the flow of information from outside and inside us. It’s the perception-action cycle: the human being (but every intelligent agent5, somehow) is not a container that records and undergoes information from outside. Perception isn’t a passive process: we put everything we see into percepts that guide our search for new information.

All the images we see, study and come into contact with change our mental structures and then return to the world as pictures reprocessed. But not only that: all these inputs create complex impressions, modify attitudes, and guide behavior and subsequent image-seeking. It’s a continuous, dynamic flow. It’s part of the power of images.

«It is not enough to say that the work of art “gives something to think about” one must say, rather, that the work will be such if and only if it’s capable of occasioning thought». Pietro Montani, L’estetica contemporanea (Contemporary Aesthetic). Carocci, 2004.

In European and American Psychology, mental structures are called schemas. These knowledge structures specify the general properties of any object or event we encounter. We have schemas for everything, even people, roles, actions, and ourselves. They are abstract representations, essential traits. It’s information in long-term memory.

«Images are not stored as facsimile copies of objects, or events, or words, or phrases; the brain does not encase polaroid photos of people, things, or landscapes; it does not store recorded tapes of music and speeches or movies of episodes in our lives; it does not store within itself reminder sheets and transparencies […]. In short, it seems that there are no permanently deposited images of anything, not even miniaturized ones […]. In the course of one’s existence, each of us acquires a flood of knowledge so that any archiving would pose insurmountable capacity problems. If the brain could be likened to a library, like a library, it would soon come up short of shelves. Moreover, archiving copies usually presents not easy problems of access efficiency when they need to be found. From direct experience, we all know that when we want to recall a given object, face, or scene, we do not get an identical reproduction but rather an interpretation, a freshly reconstructed version of the original. Moreover, versions of the same original change with the passage of years and personal experience, and none are compatible with a rigid copy representation [...] memory is essentially reconstructive [...].

Mental images are temporary constructions, attempts to reproduce configurations experienced [...]. There is no single hidden formula for this reconstruction: Aunt Margaret as a complete person does not exist in a single brain site but is distributed throughout the brain, in the form of numerous dispositional representations, for this or that aspect. And when you evoke memories of things related to Aunt Margaret, she surfaces in various lower-order cortices (visual, auditory, etc…) in topographical representation. Still, she is present only in separate views during the time window in which you reconstruct some meaning of her person [...]. Suppose that fifty years from now, an imaginary experiment allowed you to plunge inside the visual dispositional representations that someone has of Aunt Marguerite; I am convinced that you would not see anything resembling Aunt Marguerite’s face because dispositional representations are not topographically organized». Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Adelphi, 2021.

Schemas are practical because they are conservative, inexpensive, and sufficiently generalizable. They allow us to perceive the world and ourselves as stable and predictable enough to make decisions, guide behavior and predict consequences with minimal effort. Without these patterns, we would be overwhelmed by everything and unable to move a muscle in even the most mundane situations.

Schemas are harmful because they are conservative, cheap, and insufficiently specific. Once formed, they lose information and tend to retain their structure. Usually, we better remember information congruent with the schema; conflicting data goes into oblivion.

Stereotypes are culturally and socially shared schemas. Formed impressions resist and are damn hard to change. It explains why it can be so tough to photograph something (or someone) we know well.

The first photographs for a new project are usually the product of these cognitive structures, and there is no easy, 100% conscious way to avoid them. Sometimes the subject carries layers of cultural and social patterns reinforced by centuries of history. Photography is a practice that only explores the surface if we stop at these first images. The first draft of anything is shit, Hemingway once said.

«And creatures poop. A lot of it. However, the parts that are not feces will take form, and this is the result of practice. Going long requires pause and reflection. Going long also requires forgiveness». Ian Lynam, The Impossibility of Silence: Writing for Designers, Artists & Photographers. Onomatopoeias, 2020.

Patterns in our heads spill over into the pictures we make but, more importantly, they guide our behavior toward similar imagery. A compass our mind uses to point us in a direction. It’s redundant. It’s a pattern constantly reinforcing itself time after time. It’s latent, implicit, and invisible to the eye.

There are no rules or exercises. Once in the universe of possibilities, everyone traces their way. Some strategies can come in handy, though.

It helps to show our photos to trusted people (but also quite distant from us) occasionally. And also, when in doubt, let them rest for a while. The patterns of our future selves are different from those we have when we take a picture. We may see something we didn’t see before.

One strategy is to look for boredom. Sometimes we feel we have a strong image. That feeling that makes neural connections tingle, where it all seems to make sense: this is when we recognize a pattern. In visual disciplines, it can be both a good and a bad signal. It depends. Maybe we can try to replicate it: by the time it becomes banal, we’ll have exhausted all the pattern possibilities. When faced with the evidence of dozens or hundreds of images that are all the same (especially if printed or during the selection process), we find the motivation to look for something else.

Another faster but “risky” method is to plan the shot in every detail and then do the exact opposite. It’s risky because sudden change requires experience and elasticity in some situations (when the work is commissioned, for example). My hard drives are full of photographs taken this way. And light proofs that are much more interesting than the “official” image. In this case, a tip to cover your (our) back is to take a safe photo anyway, even if it’s trivial. At least that way, the job is brought home.

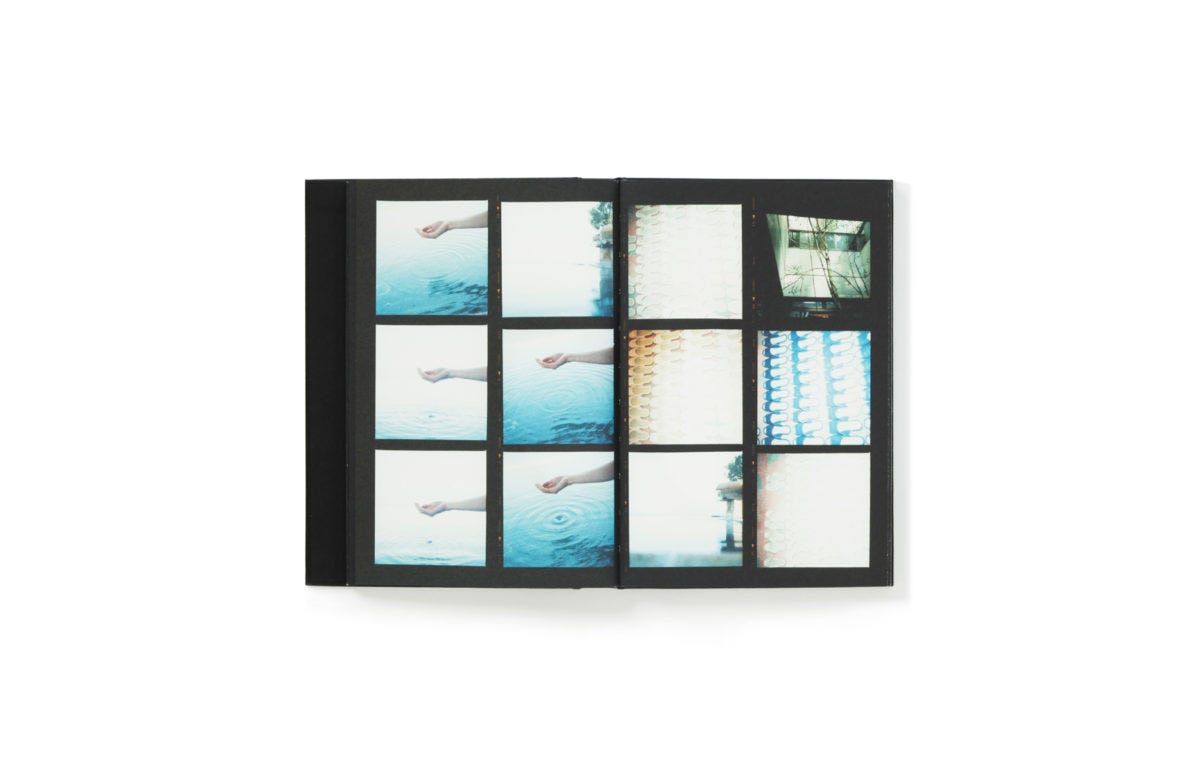

Never, NEVER underestimate the importance of mundane photographs! Always take lots and lots of them. It’s where patterns and automatisms emerge. They are essential tools for studying oneself and growing.

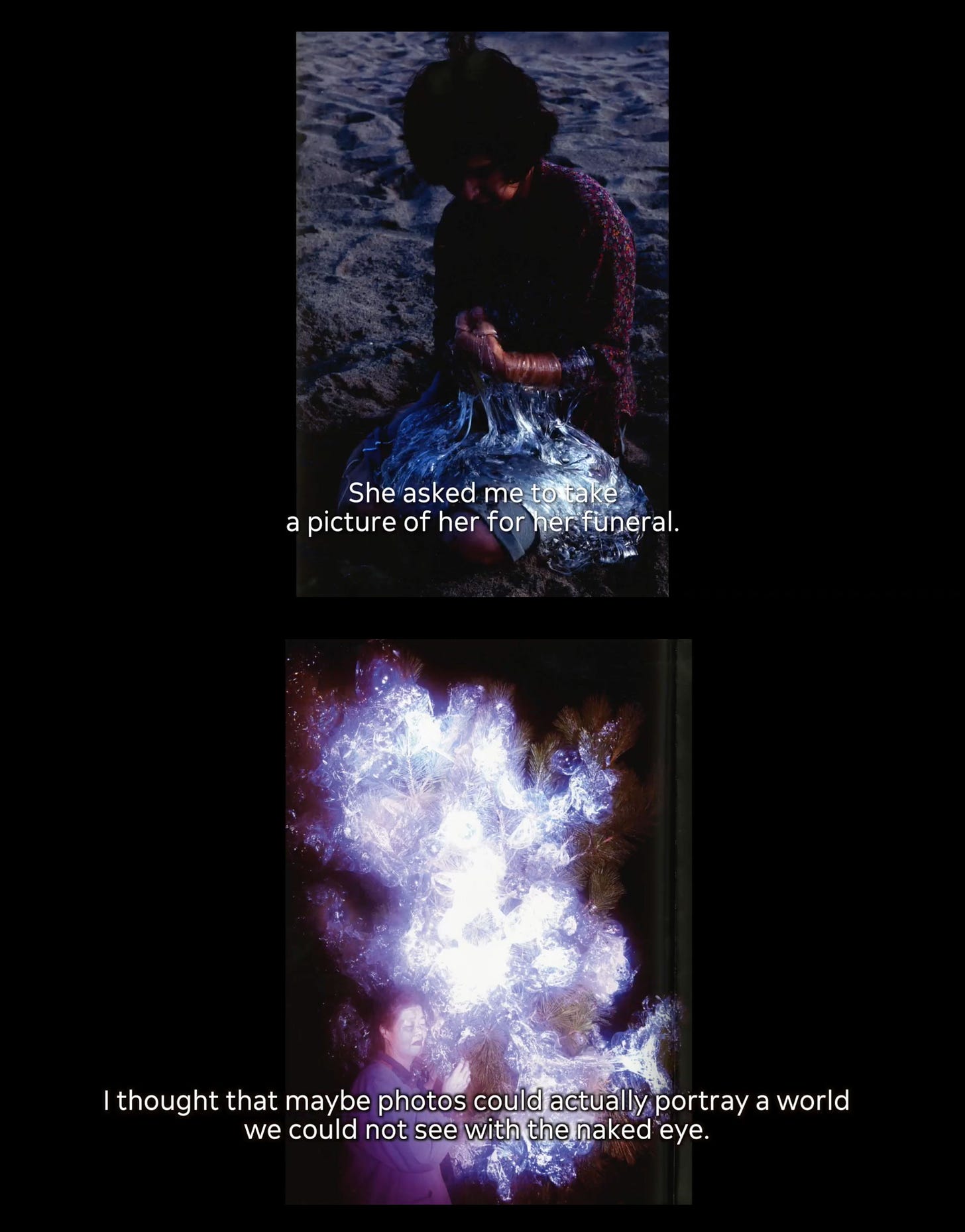

A final strategy to circumvent patterns is to let go of control (or the illusion of it) and play with chance. Self-portraiture is one example, but also collaborations with people, other living and non-living beings. Or using techniques and media that have a life of their own and are not perfectly reproducible and controllable.

Patterns are resilient, but the world requires adaptation to survive. It is a constant tension between freezing and changing. Good photography thrives on opposites, on counterpoints.

One can make pictures based on stereotypes6. Sometimes it’s what you have to do in commercial photography. Knowing patterns shared by a specific audience is critical to creating images that sell. While at other times, one can pay attention to the individuality of what is in front of the camera. It’s a continuum that depends on the situation and the image we want to create.

«For Rorty7, art is but one way to save the reasons for singularities». Pietro Montani, L’estetica contemporanea (Contemporary Aesthetic). Carocci, 2004.

Changing a pattern starts with honest and sincere exposure to the subject we approach. But openness, “being there” and studying our subject from the outside are not enough. Real change occurs through interdependence: collaboration and sharing purposes and experiences.

After spending time on the pitfalls of schemas and how to get out of them, I want to conclude by recalling what I wrote: schemas are practical because they are conservative, inexpensive, and sufficiently generalizable. They save time and cognitive resources by working for us and with us. In all situations where we are under pressure (due to lack of time, for example) or have to multi-task at the same time (such as staying present with the subject of a portrait while dealing with the technical aspects of photography), schemas intervene to make our lives easier, allowing us to direct all our attention to what is essential. Last but not least, patterns are that subtle stability recognized in a photographer’s work as the voice.

They guide intentions, choices, and behaviors, even when they appear 100% conscious. They intervene in creating sequences and in recognizing what others do not see. They are the voice, the uniqueness. That’s why they must be acknowledged, cherished, and allowed to act as much as they need to, with faith.

«I know that my photographs are influenced by photographers, painters, and writers of the past. They are also informed by my genetics, physical type, mental skills, perhaps even my astrological configuration. They are certainly affected by my upbringing, the culture of my youth and the culture of the present. They are affected by my economic status and my social relations, and by my psychological, spiritual, and aesthetic thrusts. My political point of view influences my work. Finally, the fact that all of these factors – as well as the many more that I am not aware of – are in constant flux makes it perfectly clear that I’ll never figure the damn thing out. Nor do I want to. What I can do as an artist is to accept, and if possible even embrace the fact that the puzzle is infinite; to continue to work in a craft over a period of time and to assume that a true voice will emerge. The freedom that comes from this understanding is thrilling». Philip Perkis, Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. Kindle Edition.

In Italy, we generally speak of Western and Eastern cultures, referring to the geographical areas of Europe/USA and China/Japan/Southeast Asia. It would be correct to talk of individualist and collectivist societies and cultures, with the understanding that these are not clear-cut and opposite categories but a spectrum between two poles. In Italy, for example, both individualist realities (large cities and major centers) and collectivist realities (rural communities, small provincial towns) coexist.

While writing this, I had fun browsing through creation myths on Wikipedia.

It’s a mechanism that goes into the group of self-serving biases. They distort reasoning to help us feel “a little bit better” than we are and protect our self-esteem.

I was uncertain about using the terms living being or intelligent agent. Ultimately, I chose the latter because, in this day and age, neural networks and artificial intelligence also function (oversimplifying) in this way. We are all intelligent agents: people, animals, plants, bacteria, and AI.

Here I use the term stereotype without negative meaning to refer to the abstract and general representation of someone or something.

Richard Rorty, philosopher.