#EN1.4 Awkward and uneasy

When dealing with people, no one system works for everyone.

One of the key features of my photographic process is feeling awkward and uneasy. Honestly, I think a certain amount of embarrassment is part of the photography package, especially when dealing with people.

Yet scrolling through social feeds, I see dozens of photographers who seem so proud and confident in their skin. I know that in many cases, what I’m looking at is pure marketing or a fake-it-till-you-make-it1 strategy, but there are times when I can’t help but confront myself. I know it is an unhealthy approach that leads to distorted conclusions. I have to pinch myself before I find myself in the nightmare of “I can’t do anything good” for the rest of the day (actually, it is usually Luigi who pinches me, there are days when I am very vulnerable to the negative influences of social media).

Over time I learned to mask the discomfort and live with it, but I felt alone, like the only one who couldn’t solve that problem. I researched and asked questions. I would have loved to hear from someone about a five-simple-steps-system that would get me over that difficulty. But instead, I got testimonials from other experiences, which, after all, turned out to be much better. I have been photographing for some years, and the five-simple-steps-system is nowhere to be found.

This article will focus on portraiture, so much of the awkwardness and uneasiness concerns dealing with other people. Still, I’m sure every genre of photography has its own crux.

«Q: How did you overcome your fear of photographing people?

Soth: I started out with kids because that was less threatening. I eventually worked my way up to every type of person. At first, I trembled every time I took a picture. My confidence grew, but it took a long time. I still get nervous today. When I shoot assignments I’m notorious amongst my assistants for sweating. It’s very embarrassing. I did a picture for the The New Yorker recently and I was drenched in sweat by the end and it was the middle of winter». Alec Soth, alecsoth.com, 2007.

When I started with portraiture, I spent a lot of time studying people, trying to figure out the best strategies to bring home the photograph I had in mind and to make them comfortable. I wanted to build myself a system, an effective method for every occasion. I started reading psychology manuals and articles to understand and photograph others better. But sometimes, when you go on a journey to learn about another world, you come home knowing yourself better.

When dealing with people, no one system works for everyone.

Just as there is no preset that gives good results on all images. If you ask me, good education and behaving like a decent human are the basics. From there on, it’s a matter of building a relationship with the subject over time and with the limitations we’ve been given. This is one of my staples, it’s part of how I approach portraiture, but I know it’s not the only approach.

Suppose you live and work in New York City, where people can be quite accustomed to meeting weirdos while they walk down the street minding their business. You can even shoot a flash in someone’s face without making much of it. In fact, you can do it even in a small community where everyone knows you. Still, the implications and consequences and the final images would be different. I find it very difficult to imagine myself in Bruce Gilden’s approach; his method is on the extreme edge of what in my mind is “the portrait”, although I find some of his images interesting.

The needle of the balance in Bruce Gilden’s portraits is all shifted toward outward appearance. As he recounts at the beginning of the video, it is the look of a child who spends his time observing the characters parading past his house on the crowded streets of New York City. His close-ups are masks so rich in detail that I find it difficult to empathize with the people portrayed; I have a hard time imagining their inner life, what they are thinking, or their daily vicissitudes. It exists only in terms of what is here and now in front of the camera. I find it a ruthless look at a grotesque world.

Opposite Bruce Gilden I think of Alessandra Sanguinetti’s work with Guille and Belinda in which she followed her subjects for years (two decades at least). The one documented is not a rich, glossy reality. The world this photograph gives us back is nuanced and magical and takes me beyond what I see in the frame.

So is it time that defines a portrait’s depth? Does working quickly and without involvement capture only the surface? Is investing time and emotion in long-term projects the only way to dig deeper?

Time is undoubtedly a variable, but it is only one factor that comes into play. And I dare say not even one of the most important. Many magnificent and intense portraits of strangers were taken in only a few hours or minutes. It is not so much the time that is important but the quality of the relationship. The connection between two people even goes so far as to distort the perception of time’s flow. Sometimes you talk to another human being for a few hours but feel like you have known them forever. What matters is not the objective time itself but the feeling of it.

Richard Renaldi’s approach and motivations are different. The short video above shows how he works, so I won’t explain more. Still, it describes very well the search for connection. Renaldi photographs strangers approached in public places, accepting the possibility of rejection or of things not working out. By bringing different individuals together, he creates a powerful visual counterpoint. If this work fascinates you, I recommend this video (it lasts about an hour).

Every relationship is a system of forces.

It can be balanced or unbalanced. In this case, someone has the power, and someone is being led (or subjected to). Portraiture can also be seen as a relationship between those with the decision-making power (those who photograph) and those in the vulnerable position of letting themselves be guided (those in front of the camera). I was taught that there is always a manipulative component to portraiture. History is full of photographers who use tricks or gimmicks to get the image they have in mind.

To give an example without bothering history, even a wedding photographer has an arsenal of jokes to make the bride and groom smile. From this perspective, the portrait becomes a role play, a dance in which photographers try to take people where they want to go, either accompanying or forcing them.

With time and experience, I have understood and learned the rules of this dance, but I remain a terrible dancer. When I’m photographing, I have a huge struggle to step into the role of guide-manipulator. I know how to do it, but I always feel discomfort from living in a false, constructed situation. When people realize they’re being photographed, my presence somehow affects them, I understand that. And I also know that, albeit implicitly, I do everything I can to get where I want to be. But I can never force it. I feel much closer to Renaldi’s approach, ready to accept even rejection, than Avedon’s.

When I realized that I could only work on people up to a certain point, I began to focus on another component of the relationship with the portrait: myself. In the beginning, it was tough.

Just as I had tried to study people to learn how to control them for my own purposes, I was now trying to manipulate myself.

But there is a part of me that cannot accept this compulsion. And I just can’t fake it when I don’t feel comfortable, so my difficulties have only increased2.

Imagine the situation: on one side was the ideal version of the me-photographer, the perfect one. Conversely, the human-me-photographer made mistakes, got stuck, and short-circuited. Despite everything, she also remained professional, bringing the work home. And she was the only one the clients saw since the perfect version lived only in my head and didn’t bother to come out and help me.

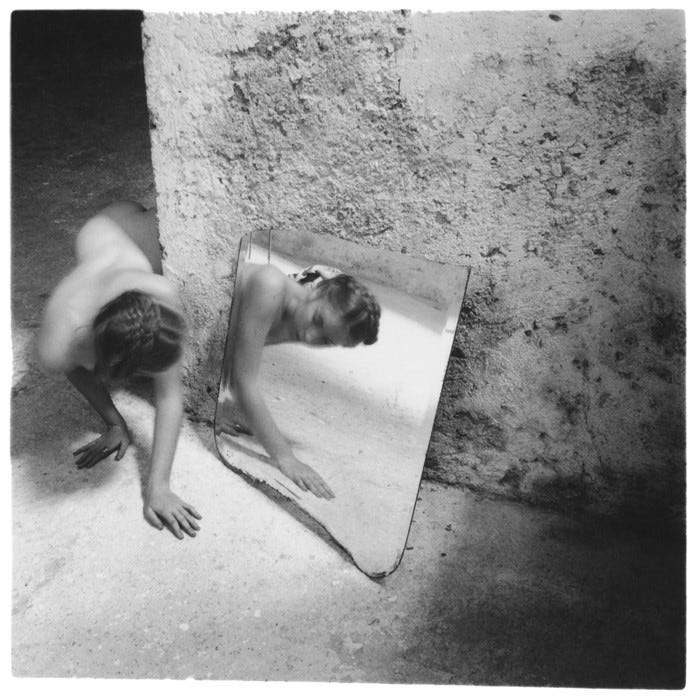

We all have different versions of ourselves.

How we are, how we would like to be, and how others would like us to be. When we turn our attention toward ourselves, as if we were an object or another person, we inevitably compare these selves. This is what social psychology calls objective self-awareness. A self-esteem decline can also occur when there is a substantial discrepancy between the “ideal” self and the “real” self. Many people, including myself, cannot listen to their recorded voice without feeling discomfort: it sounds different and unpleasant from what we think we have. This is objective self-awareness.

The phenomenon also occurs when a person looks at himself in a mirror or portrays himself in a photograph. Comparing one’s personal version of self with a version condensed into an object (the photograph) threatens self-esteem. Annoyance or rejection in seeing oneself again is a defense mechanism3. Conversely, seeing oneself in a good portrait or even just seeing oneself represented can boost one’s self-esteem; photography is a potent tool.

If confronting our image can bring insecurity and rejection, the photographers who too often compare the version of self they perceive as real with the ideal one in their minds or projected by others (often only for boorish marketing) can feel incapable and wrong in their approach. And that’s what was happening to me: by failing to be the way I wanted to be, I was losing self-confidence by letting myself be pulled, without realizing it, into a downward spiral.

The cognitive resources we need to create, such as memory and attention, are limited.

They are the essential tools of creativity. The more significant the portion of these precious resources are committed to something else, from fear of mistakes or any form of behavior control, the smaller the part we will have available to photograph. Trying to judge ourselves from the outside while doing something is like putting a spoke in our wheel when learning to ride a bicycle.

Self-monitoring (usually) comes into play when we face an unfamiliar situation, such as photographing someone for the first time or speaking a second language we don’t use daily. They say having a few beers improves speaking a foreign language skills. It’s true: alcohol inhibits control by freeing up resources. A drink relaxes, but it is not a solution.

«In 1978, in January, I stopped drinking. I had never thought drinking made me a writer, but now I suddenly thought not drinking might make me stop. In my mind, drinking and writing went together like, well, scotch and soda. For me, the trick was always getting past the fear and onto the page. I was playing beat the clock—trying to write before the booze closed in like fog and my window of creativity was blocked again.

[...]

I told myself that if sobriety meant no creativity I did not want to be sober. Yet I recognized that drinking would kill me and the creativity. I needed to learn to write sober—or else give up writing entirely. Necessity, not virtue, was the beginning of my spirituality. I was forced to find a new creative path.

[...]

Writing became more like eavesdropping and less like inventing a nuclear bomb. It wasn’t so tricky, and it didn’t blow up on me anymore. I didn’t have to be in the mood. I didn’t have to take my emotional temperature to see if inspiration was pending. I simply wrote. No negotiations. Good, bad? None of my business. I wasn’t doing it. By resigning as the self- conscious author, I wrote freely.

[...]

In retrospect, I am astounded I could let go of the drama of being a suffering artist. Nothing dies harder than a bad idea. And few ideas are worse than the ones we have about art. We can charge so many things off to our suffering- artist identity: drunkenness, promiscuity, fiscal problems, a certain ruthlessness or self-destructiveness in matters of the heart. We all know how broke-crazy-promiscuous-unreliable artists are. And if they don’t have to be, then what’s my excuse?

The idea that I could be sane, sober, and creative terrified me, implying, as it did, the possibility of personal accountability. “You mean if I have these gifts, I’m supposed to use them?” Yes». Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way. Penguin, 2016.

The “genius and recklessness” approach is not healthy. I believe in maintaining a healthy personal, professional, and authorial life to remain productive. I never reached the point where I turned to alcohol to hush my anxieties. Still, for a while, I developed a kind of workaholic addiction (and the term workaholic 100% fits here), according to which I felt pretty prepared only after I exhausted myself, analyzing and controlling every moment of my life as a photographer.

I wasn’t doing well, and no great images emerged from that period. I worked a lot and produced little. I hit rock bottom when I decided to turn in a series of photographs that I knew had significant flaws simply because I couldn’t stand them anymore. Needless to say, the work returned, I had to re-work it (rightly so), and I didn’t leave a good impression on the client.

Since then, I’ve continued to photograph and produce images. But my final goal wasn’t to take a better picture than the day before, to become the ideal photographer I had in my head and saw in others, but to feel my body in different situations. To make peace with my way of photographing and experiencing the relationship with the subject.

I stopped putting people and myself under a magnifying glass to try to understand them. What a person has inside is not investigable by anyone. Individuals are too fluid and mysterious to be fully understood (or portrayed). Portraits lose their magic or become something else if manipulated too much.

In photographing someone, I still feel awkward. For a long time, I thought it depended on a lack or inability on my part. It was an external flaw to be eliminated. But now I see this is a part of me. I try to listen to it instead of fighting a battle already lost.

«My own awkwardness comforts people, I think. It’s part of the exchange». Alec Soth, New York Times, 2009.

Up to this point, I have focused on internal mechanisms, as if the photographer and subject live in a bubble where nothing else exists. But I would like to spend a few words about the influence of context. One of the most challenging things I find is photographing with someone watching me. A boyfriend, a client, anyone. My performance drops dramatically, and I start making mistakes I wouldn’t otherwise make. The social context can become a potent inhibitor.

Suddenly one has the impression of being naked under a spotlight, that all anxieties are apparent and every action is scrutinized and judged. In such cases, I implode.

When this happens, I struggle to hold all my pieces together. But as I continue to practice and focus on progress rather than flaws, I am learning that all these phenomena are not my stuff. I feel them, they exist, but they can’t harm me until I pay attention to them and give them the power to do so4. Sometimes it isn’t easy. In those cases, the good old stop and breath is an excellent place to start. And sometimes things don’t work out, no matter what we do, and that’s okay.

«IC: Your portraiture always feel incredibly sensitive no matter the subject, what advice would you give photographers wanting to shoot a similar style of portraiture, in order to respect subjects?

GM: My mother taught me empathy by telling me that everyone was going through something. No matter who they are, rich or poor, they are probably struggling on some level. When I come upon a scene or a person, I assume that person is in the midst of some conflict. I will never know, and I don’t need to know to make a good picture, but I think that influences how I see people and how I photograph them.

Having said that, when I make a picture, my camera is not the easiest camera with which to be photographed. I’m pretty fast by large format standards, but still people have to wait for me to focus and often more than once. People tell me it feels like they are at the dentist or getting a chest X Ray. So I can’t say it feels very tender at the moment of making the picture. I do have great patience though. Sometimes a picture will fall apart in the making of it. That’s hard but my subjects are rarely a guarantee. These are not professional models, they are regular people that didn’t know they were going to be photographed today (or ever), so I can’t get upset if it doesn’t work out. Me being a photographer is about me. As a group, photographers can be egomaniacs. Some photographers show up thinking everything revolves around them and when the whole thing collapses, they get mad at everyone as if it’s someone else's fault they’re not good photographers. That’s nuts. For me, it’s all my responsibility, the light, time of day, my subjects listening to me, not listening to me. I have to take it all on because this is my venture, not theirs or anyone else's.

But even still, when a picture doesn’t work out, I can still be heartbroken. When I teach large format, I tell my students that the dark cloth is so you can hide behind the camera and cry». Greg Miller, Q&A: in conversation with Greg Miller. Intrepid Camera, March 2020.

Fake it till you make it. In recent years this phrase has become one of the pillars of self-improvement and motivational coaching. From a psychological point of view, there’s a world behind these words involving the sense of identity, self-esteem, attitudes, and behaviors. This “magic formula” doesn’t always lead to positive effects. But this is a story for another time.

Social psychology would describe me as a low self-monitoring person, that is, one who tends to act in every situation according to their internal states and values. The opposite is a highly self-monitoring person, a “social chameleon”, who can adapt to any situation to present their best self. Self-expression versus self-presentation.

This one would deserve a lengthy elaboration, like so many other topics discussed. I will stop at the threshold by mentioning this physiological mechanism without entering the clinical field, as in the case of body dysmorphism disorder.

In social psychology, they talk about social inhibition and facilitation, the illusion of transparency, the spotlight effect, and causal attribution errors.