#EN1.7 An ode to idleness

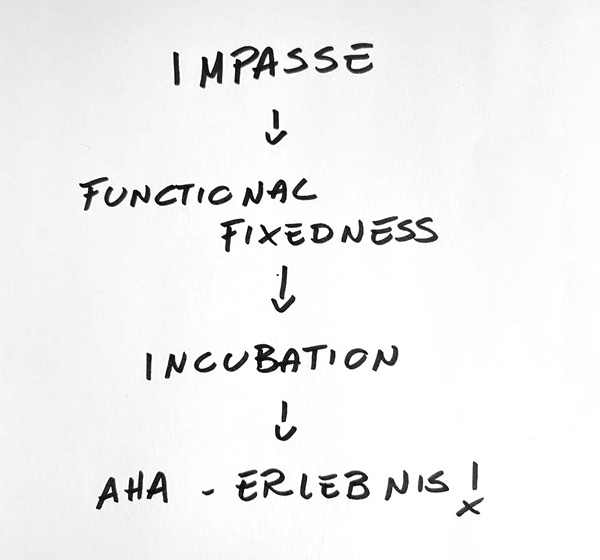

Least effort principle and productive thinking.

Wolves spend most of their lives lazing around. I didn’t note the references, but a few months ago I stumbled upon this study that followed the life of a pack in the wild:

- When food abounds and there are no threats, wolves loaf because they have everything they need to live comfortably.

- When resources are scarce, wolves laze around to preserve energy.

In conclusion: in wolves’ everyday life, napping is an appropriate reaction to most situations (basic survival activities aside).

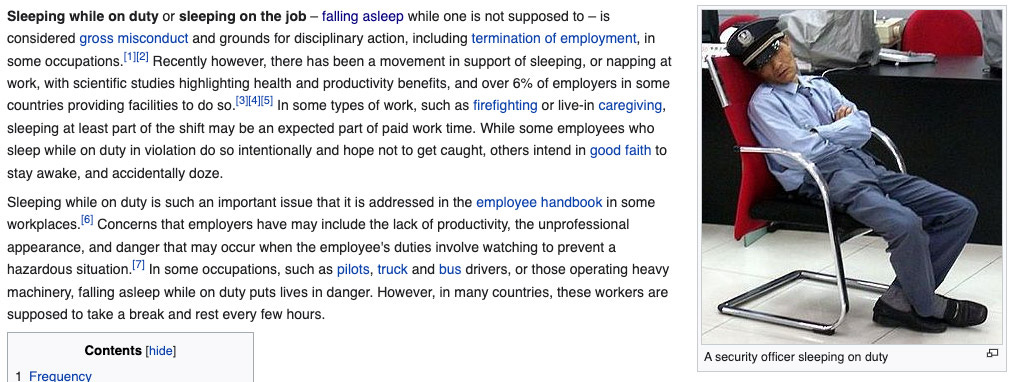

Rest is rarely seen as a fundamental activity in our society. The word activity itself is the opposite of rest. Apart from 6-8 hours of sleep at night, universally recognized because prescribed by medicine, resting is mainly seen as non-productive, dead-time. Or as a necessary consequence of work, preferably intense, or a reward, a vacation. Rest is deserved and guilt-free only when one gets there tired, exhausted, and worn out. The main goal is always to recover energy, rarely to accumulate or keep it from dissipating. We plan calendars according to commitments. We don’t count breaks. Rests are gaps to be filled, usually with other activities. But white spaces and breaks are two different things. Music notation, like writing, has specific marks to indicate pauses. They are not placeholders that can be filled in with something else.

The sleep-wake cycle as we know it today is a modern invention, born roughly with the industrial revolution and the need to schedule activities into rest-work shifts to maximize productivity. This approach is not 100% bad. Still, it becomes so when there is a strong tendency toward organizing time only in terms of profit. Trying to manage time differently becomes increasingly tricky and socially sanctioned. Social sanctions include objective punishments, but implicit forms such as guilt or disguised jokes also count. Or transparent structures and mechanisms that are repeated and reinforced, such as those that lead us to fill ourselves with commitments and life goals.

Sometimes I think that even idleness is becoming a form of privilege. I am not just referring to affording a vacation, for example, but also to the instability and uncertainty that require constant adjustments and actions on our part.

In literature, acedia and idleness are two different things; only the former is a capital vice. On the one hand, there is complete indifference and apathy towards the world and oneself, letting everything go, out of inertia.

On the other hand, idleness is more related to abstaining from profit-bearing activities. Which within a capitalist system like ours sounds a lot like a mortal sin, but is a necessary component of our lives1.

Ancient people had a very different conception of idleness. In ancient Rome, otium was self-care and wisdom, as opposed to negotium, business, and all activities related to profit, public and political life. Otium was time devoted to study, social life, beauty and art, physical activity, and contemplation.

Being passive and inactive is to invest time into welcoming experiences, listening2, and patience. It’s time for oblivion. The mind clears space by forgetting bits of information, makes new connections, and prepares the ground for planting the seeds of creativity.

Otium was a practice reserved for the upper class and wealthy population. Otium was a privilege. When one needs to bring home the bacon or take care of others, time for oneself is one of the first things to go. Although in the long run, this has adverse effects even on work performance. It is a paradox: you sacrifice free time to produce and earn (perhaps) more, but in the end, you work worse and produce even less(?).

Idleness serves personal growth, soft skills development, interpersonal relationships, and management skills. It nurtures creativity. Rest enhances patience, resilience, and mental and physical health. Working requires a good energy reserve and balance between body and mind, especially if the activity is protracted in time. It is a marathon, not a 100-meter sprint.

«Practice does not make perfect. It is practice, followed by a night of sleep, that leads to perfection». Matthew Walker, Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner, 2017.

In creative jobs, such as photography, these skills must be used all at once very often. Relationship skills and problem-solving, whether to solve unexpected technical issues or to draw out creative ideas.

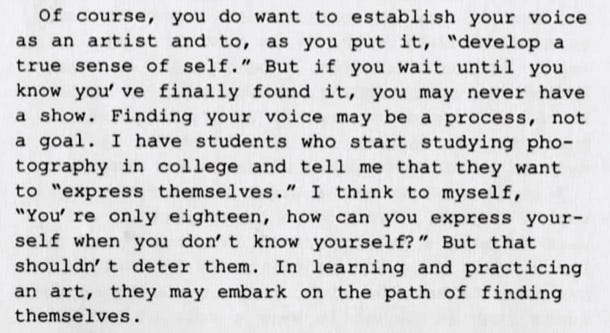

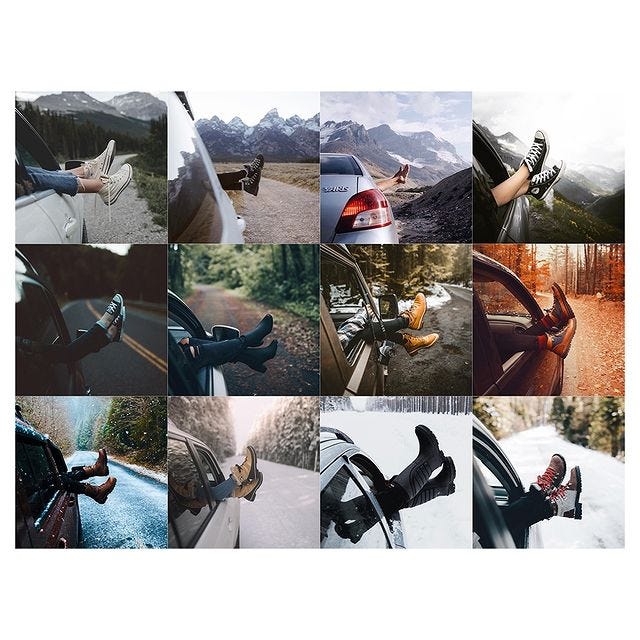

Just as a writer, no matter how good, will always read more books than they will ever be able to publish, to make good photographs, one must also absorb more than they will ever be able to throw out. From this perspective, photography is a tool to take in the world more than to express yourself.

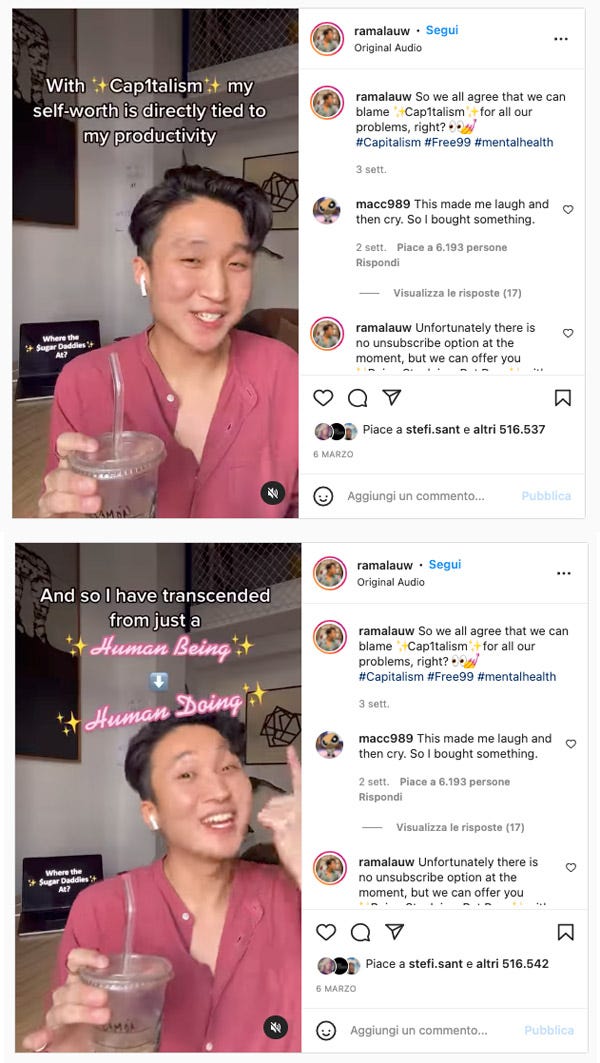

The passive phase of knowledge acquisition and reworking is equivalent to (if not greater than) the active-productive phase. When this does not happen (e.g., when you are producing content non-stop), you are in a reproductive phase, not a creative one. Reproductive thinking uses only the mental patterns already learned. A kind of assembly line, repeatable and reproducible.

Insta Repeat on Instagram: ”👟👟

#instarepeat #inspirationalquote #simulacra #internettroll #copyofacopy #beforeitwasmainstream #frequencyillusion”March 31, 2022

The assembly line is not 100% wrong: you repeat the same content that works in the same or slightly different (but equivalent) form as long as it works. That is, as long as it brings gain, visibility, or credibility. Persuasion, but also learning, comes through forms of repetition. Babies learn to use language creatively with echolalia and lallation.

In professional photography, you invest time and resources to develop a service or a product. Then you test and advertise it. If it works, you repeat the same workflow until you return the investment and make a profit. Other times you find mixed solutions, services that are a middle ground between the “standard” workflow and customization. Still, other times, entire projects are built from scratch at a different time and economic cost. Repeatability makes it possible to provide a consolidated service at a low price. As far as I’m concerned, sometimes it’s a matter of deciding between providing a handcrafted product and an industrial one or any solution, depending on what is needed.

Reproduction is good, then. The problem arises when the assembly line is presented as a creative process. Productive thinking modifies already learned patterns. It combines concepts and elements. Nothing is created from nothing, and everything is a remix; creativity requires time and contamination.

«The artist is a collector. Not a hoarder, mind you, there’s a difference: hoarders collect indiscriminately, artists collect selectively. They only collect things that they really love». Austin Kleon, Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative. Workman Publishing Company, Kindle Edition.

Photographers are sometimes compared to collectors of moments, referring to the products of photographic practice. This makes sense because, in the end, images are the “things” we leave behind, like the trail of a snail. But perhaps, instead, it is more about collecting experiences. One of the most rewarding aspects of photography is that it gives me access to various situations. Sometimes it is a real excuse to connect with new people and otherwise inaccessible experiences.

The pleasure of adventure and exploration, to discover new points of view. To me, photography has less to do with what or how much I have already produced and more with where it will get me and what I will discover.

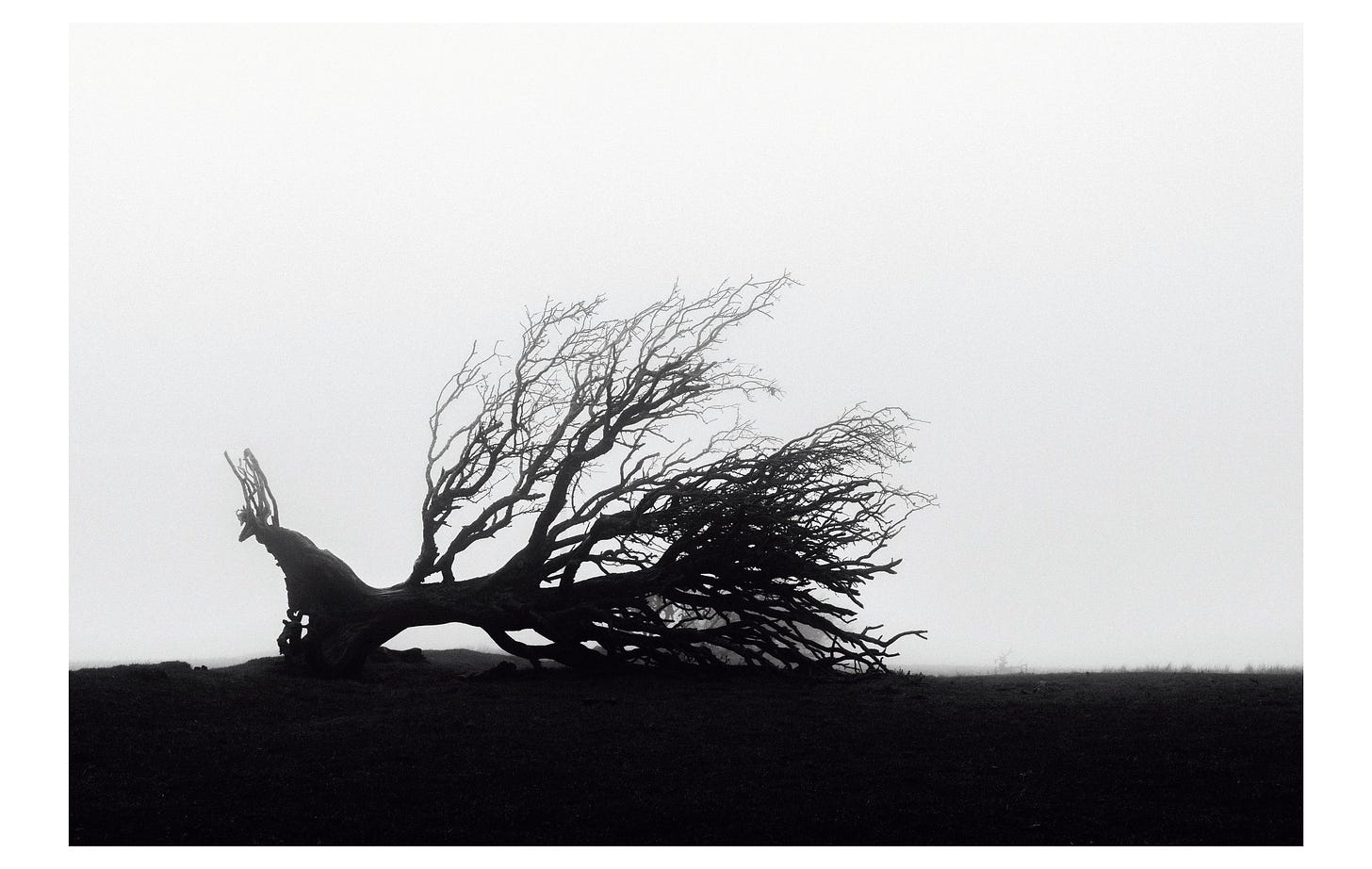

The time I spend exploring does not directly generate profit. It is not “productive”. It is not performance. It is idleness and indispensable for restoring resources and ideas. It is the process of cultivation that follows the natural cycle of the seasons, like letting the soil rest in Winter and preparing it for the next year. Of course, there are ways to work the land intensively to make the most profit in the least amount of time, but this is an unsustainable exploitation of limited resources. The soil remains parched and polluted, and photographers become frustrated and unmotivated. But everyone is free to decide how to cultivate their garden.

The last few years have been exhausting, and I think the whole world needs to slow down a bit. We’re starting to talk about slow living, the Great Resignation, and stories of alternative lifestyles are popping up. So many good resolutions, sure. But the problem is that putting them into practice rarely is a piece of cake.

I write this not with a defeatist intent but because, in my opinion, not enough emphasis is placed on the factors that come into play when you want to achieve something. Sometimes it is easy. Sometimes it is complicated.

This is a nice video, but it focuses too much on the individual’s choices and biases, conveying that responsibility for change is only individual responsibility. This way of thinking is a child of the good old “if you want to, you can”.

Even when the only thing standing between us and achieving a goal is our will, breaking our patterns is always challenging: there are so many factors at play. Slowing down and giving up an oppressive lifestyle, working well and sustainably, is often a luxury. It is not always possible and depends both on personal decisions and situations. Somewhat like in ancient Rome, otium is a privilege for the wealthy. Everyone else is being dismissed with two words:

«And maybe you have no choice about your life at all, in which case, I’m sorry that you just spent five minutes watching this». New York Times Opinion, The Bravest Thing You Can Do Is Quit.

To break and change specific patterns, one must first recognize them and realize how one feels about them.

There is a frustrating mechanism in photography, sometimes. It stems from the romantic idea of the photographer as a middle ground between “do what you love, and you’ll never work a day in your life”3 and the artist who works all hours, sends WeTransfer at 2 a.m. and is always available.

So, it is true that photography as a professional activity can have wacky schedules, busy work periods buffered by tight deadlines, endless moments of panic, and fire in the ass. You work with people, and the logistics can get exhausting, budgets are minimal, and margins for error and profit are tight.

However.

Don’t we photographers linger too long in telling us how much we work? I mean quantitatively: hours spent shooting, miles traveled, gigs of images to deliver. As if it’s a way of keeping track and confirming that we are working. Do I only perceive this on social media? Sometimes, not every time. And I count myself in the group too.

We are full of stories about how hard we are always working, but where are the narratives that show us how to work better? How do I save energy? How do I work smarter without exhausting myself? How do I make my task easier instead of more complicated?

Psychological and emotional resources are a bit like money. Spending it all is never an issue. The hard part is finding a way to save it. Time and money are the same. You show yourself available, get distracted momentarily, and poof...it’s all gone.

I think it’s time to file down a bit the stereotype of the tormented artist who is exhausted in the name of his work. This toxic photography that consumes those who produce it is a terrible reality I don’t want to feed.

It’s a common belief that the artist must always sacrifice some of their mental and physical health in the creative process. The reality is different: artists’ mental health, throughout history, is often related to low wages, grueling work hours, and contexts that do not allow them to practice and live healthy life at the same time. Exhaustion has little to do with the value of a work. Except when the artist kicks the bucket. But then someone else gets all the money.

We live in a moment in history characterized by tools to nurture creativity and spread ideas, and that’s great. Still, some situations remind me more of intensive talent breeding.

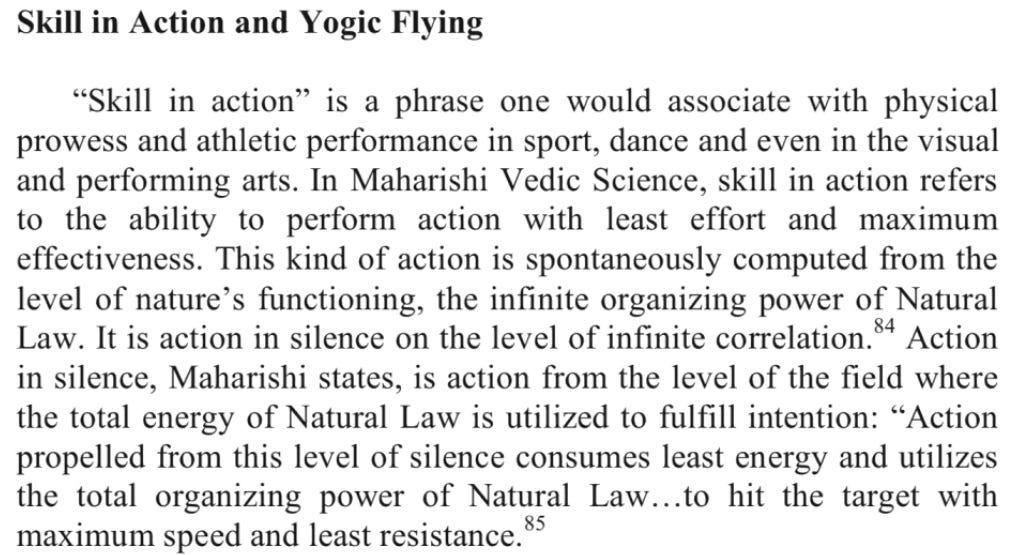

Human beings per se are not exceptionally resilient, strong, or suited to the wear and tear of continuous work. We have come so far by learning to preserve strength, among other things. The principle of minimum effort is based on an economy-oriented approach, in which I invest the minimum resources I need to achieve a satisfactory result. A dash of minimum effort pops up in all scientific and philosophical disciplines.

It is an absurdly simple concept. Using more than is necessary makes little sense. Yet, in the creative fields, we are taught to always give it our all and that the best results are achieved by pushing the limits and putting ourselves outside our comfort zone. If you can accomplish something quickly, it seems it is not deserved, or maybe you could have achieved more. As if giving everything is the only condition for getting something in return. But it is not guaranteed; it is an approach that creates dangerous expectations and leaves you drained.

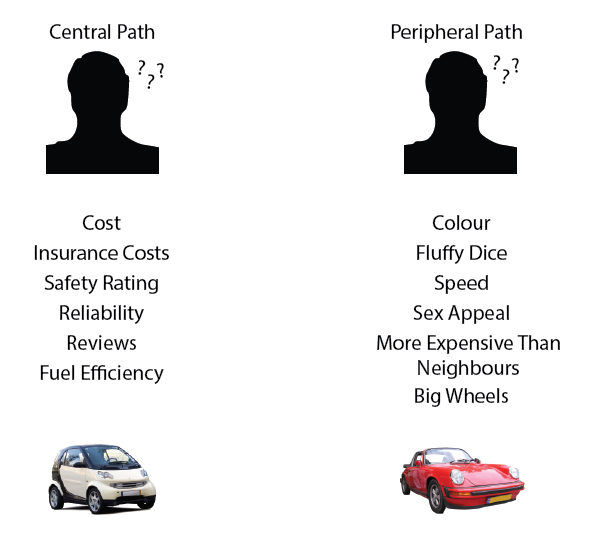

Our minds also work with a cognitive saving approach; many models describe how the brain processes information. The two-way models are especially interesting and easy: the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) of Richard Petty and John Cacioppo and the Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM) of Alice Hendrickson Eagly and Shelly Chaiken. Both argue that the mind processes incoming information through two main channels: a central/systematic and a peripheral/heuristic path. In Petty and Cacioppo’s model, the two paths are separate, while in Eagly and Chaiken’s, they are interdependent, but we will not go into detail.

The mind processes every bit of information through the central/systematic pathway. It is an accurate but costly approach. With the peripheral/heuristic route, on the other hand, the processing is much coarser; we draw sums using heuristics, a way of reasoning that allows us to arrive at plausible conclusions, most of the time, without investing too many resources. The central pathway analyzes the content and meaning of the information it receives, while the peripheral pathway deals with peripheral clues, such as the form of the message, its attractiveness, and the credibility of the source issuing it.

Usually, the mind uses the fast pathway when it does not have enough cognitive resources available, there is not much time to evaluate, or the topic is not interesting enough (low level of engagement). In contrast, if the content interests us greatly or we tend to think critically, we analyze information in great detail.

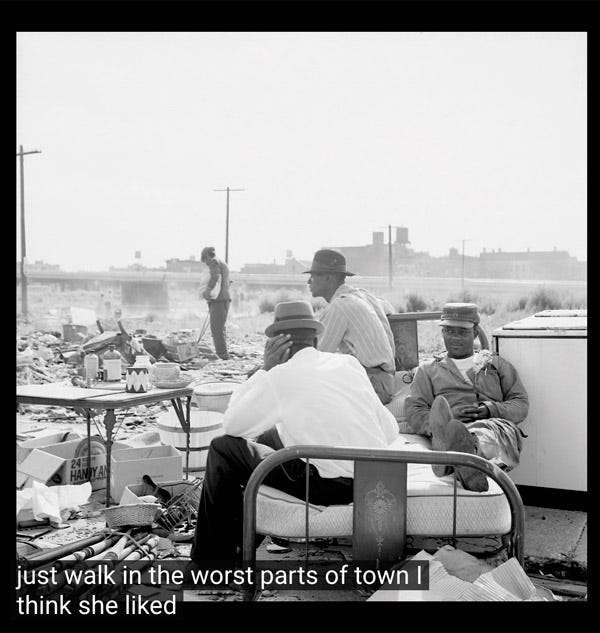

Images are peripheral clues, like all other sensory stimuli. Our mind processes them immediately, drawing conclusions so direct that they seem intuitive. Sometimes almost raw, gut, emotional reactions that we can hardly define in words because they come before any other thought.

Photographs often encapsulate a message beneath the aesthetic surface, whether intentional or interpreted by the viewer. This meaning is processed in the slow path, the critical gaze, which dissects every notion, from the technique used to the context or the author’s biography.

No one way is better than the other. They capture different aspects. The point is not to establish the best approach but to take advantage of the more efficient at a given moment. Sometimes there is a tendency to give too much weight to critical thinking by somewhat disfavoring gut impressions. In such cases, we make so many words about the image that they only lead to the exaltation of the person who utters them in a vain attempt to corral the immensity of feeling into a concept.

«Words that do not hit the mark, words that are devalued, left in the head or on the tip of the tongue, others that instead wiggle around wildly, for fear of not being expressive enough». Edoardo Albinati, Velo pietoso. Una stagione di retorica (Pitiful Veil. A season of rhetoric). Rizzoli, 2021.

There is also the opposite: everything is judged in terms of likes/dislikes as divine law. In addition to a simple and pure pleasure of aesthetic enjoyment, gut responses give clues to an image’s emotional and sensory truths, making it immediate and not hyper-reasoned.

«If anything, it can be more intentional because it involves more of me in the activity. In a sense, I’m turning some of the responsibility over to my instinct, impulse and receptivity, and taking a little heat off my mind, which just might let it function better than when it has to carry the whole weight of the job». Philip Perkis, Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. OB Press and RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press.

Every now and then, I look at something by paying attention to both one way and the other. I may jot down feelings before and thoughts after in a notebook, sometimes not, depending on how much time and desire I have to exercise.

It can also be done with the New York Times video above. What and how many are the peripheral clues (images, sounds, text but the sudden changes in font size or tone of voice)? And what, on the other hand, are the concepts passed on and remain in the head?

I can also use the same approach to “reading” photographs. The most powerful ones are always like onions. They stay in your head and return something whenever you look at them. They have the advantage of dual encoding: the information stored in our head in emotional and cognitive forms is more robust and lingers longer.

It is a gaze of both criticism and pleasure, which enjoys the sensations the image returns and analyzes as well. It does not directly produce profit, but it fuels motivation. It fills the well. It is what takes care of those behind the camera, whatever you want to call it.

«When I made The Black Rose, which was seven years of work and took up the whole ground floor of the Art Gallery of South Australia and nearly killed me, I didn’t think I’d take another picture after that. I thought I was done and dusted. I put every ounce of energy I had over those seven years into trying to discover the meaning of life using the camera. And by the time I’d finished, I was just absolutely mentally shot. I sort of had a period where I thought, “Well, I'm done with photography. I’ve been shooting since I was 13 years old. I’ve explored every single option that I can,” and there was a sort of feeling of that’s it. But when we came to Adelaide, that was one of the reasons to shoot a body of work here: the light here is so different from everywhere else, and you get that amazing light all the way down to the horizon at the beach. Something takes over, something catches your eye and you become drawn into something else. And that's basically how The Crimson Line started. I became sort of fascinated with this particular color in the sky. And I would only shoot at the very first five minutes of the day of sunlight». Trent Parke, Interview on Monster Children. May 2020.

Domenico De Masi’s Creative Idleness.

I mean passive listening, absorbing even without communicative purpose.

In the last couple of years, I have noticed a decline in these motivational quotes. Still, it is likely because I am slowly withdrawing from social and my references are changing.