#EN2.2 Stereotypes

Still talking about them.

Let's pick up where we left off and talk about stereotypes some more.

According to social influence theories (that include studies on propaganda), it is effective to psychologize one or more individuals by shifting the focus from "what they are saying" to "they are saying it because they are so-and-so". This approach stops people from listening to their reasons and understanding their discomfort and possible causes.

Assigning complete responsibility for an individual's "deviant" behavior renders it as a personal trait, disconnected from its social and contextual roots. In this way, any disorder is deemed as a mere malfunction of the individual, rather than an expression of societal factors that contribute to it.

«The current ruling ontology denies any possibility of a social causation of mental illness. The chemico-biologization of mental illness is of course strictly commensurate with its de-politicization. Considering mental illness an individual chemico-biological problem has enormous benefits for capitalism. First, it reinforces Capital’s drive towards atomistic individualization (you are sick because of your brain chemistry). Second, it provides an enormously lucrative market in which multinational pharmaceutical companies can peddle their pharmaceuticals (we can cure you with our SSRIs). It goes without saying that all mental illnesses are neurologically instantiated, but this says nothing about their causation. If it is true, for instance, that depression is constituted by low serotonin levels, what still needs to be explained is why particular individuals have low levels of serotonin. This requires a social and political explanation; and the task of repoliticizing mental illness is an urgent one if the left wants to challenge capitalist realism». Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism. Kindle Edition.

There are powerful stereotypes in our society that fuel prejudice and discrimination. Photography plays a crucial role in this discourse because part of the mechanism operates through images.

«The apparent "innocence" of photography is part of its rhetorical power, a power multiplied in every reproduction of that image, which we see as something that appears "as it is." Photographs give the illusion of transparent access to "reality", understood as the true "language" of photography». David Bate, Photography: The Key Concepts.

These days, I am playing with image-generating AIs because it is very easy to spot learned biases and stereotypes in their output.

When I come across various images, advertisements, movies or anything that comes under my nose, I always question the cultural significance of what I'm looking at. I try to understand what kind of thoughts or emotions are being conveyed through these images and what kind of message is being left out.

«Barthes presupposed this rhetoric of an image by distinguishing between denotation and connotation in a photograph. "Denotation" is "what we see", what can be described as simply 'there' in the image. "Connotation" is the immediate cultural meaning that is derived from what is seen but is not in fact in the photograph. In practice, we rarely make similar distinctions because they appear in the same instant as obvious performances of the photograph». David Bate, Photography: The Key Concepts.

In looking at a photograph, the meanings we see reflect our mental structures and stereotypes of individuals and behaviors.

We all have stereotypes, but that doesn't necessarily mean that we have negative prejudices or behave discriminatorily towards others every day. However, even if we do, it's possible that we might not even notice it or recognize it as a problem. This is because it's often difficult to identify our own biases, especially if they're deeply ingrained and considered normal in our culture.

«The simple distinction between denotation and connotation made earlier shows that the meaning given to a photographic image, its connotation, also depends on the culture of the observer.

[...] This passage shows that the meaning of any photograph, its connotation, is never entirely fixed. In fact, the discursive knowledge that the observer brings to the image means that the connotations of an image are always potentially plural. As Barthes states, the meaning of any photograph is polysemic». David Bate, Photography: The Key Concepts.

Stereotypes can be harmful when we associate certain physical characteristics with particular personality traits. For instance, the notion of physical beauty is often linked to desirable qualities like friendliness, warmth, and kindness. Similarly, women are often stereotyped as being too sensitive, while men are often expected to be tough and unshakeable. Such assumptions can be dangerous and unfair, perpetuating harmful biases that can have real-world consequences.

The term "stereotype" usually refers to an average, sometimes distorted, representation of something. Many things are considered socially acceptable simply because they fit into this structure. However, this is not always a bad thing. We will discuss the social functions of stereotypes next time.

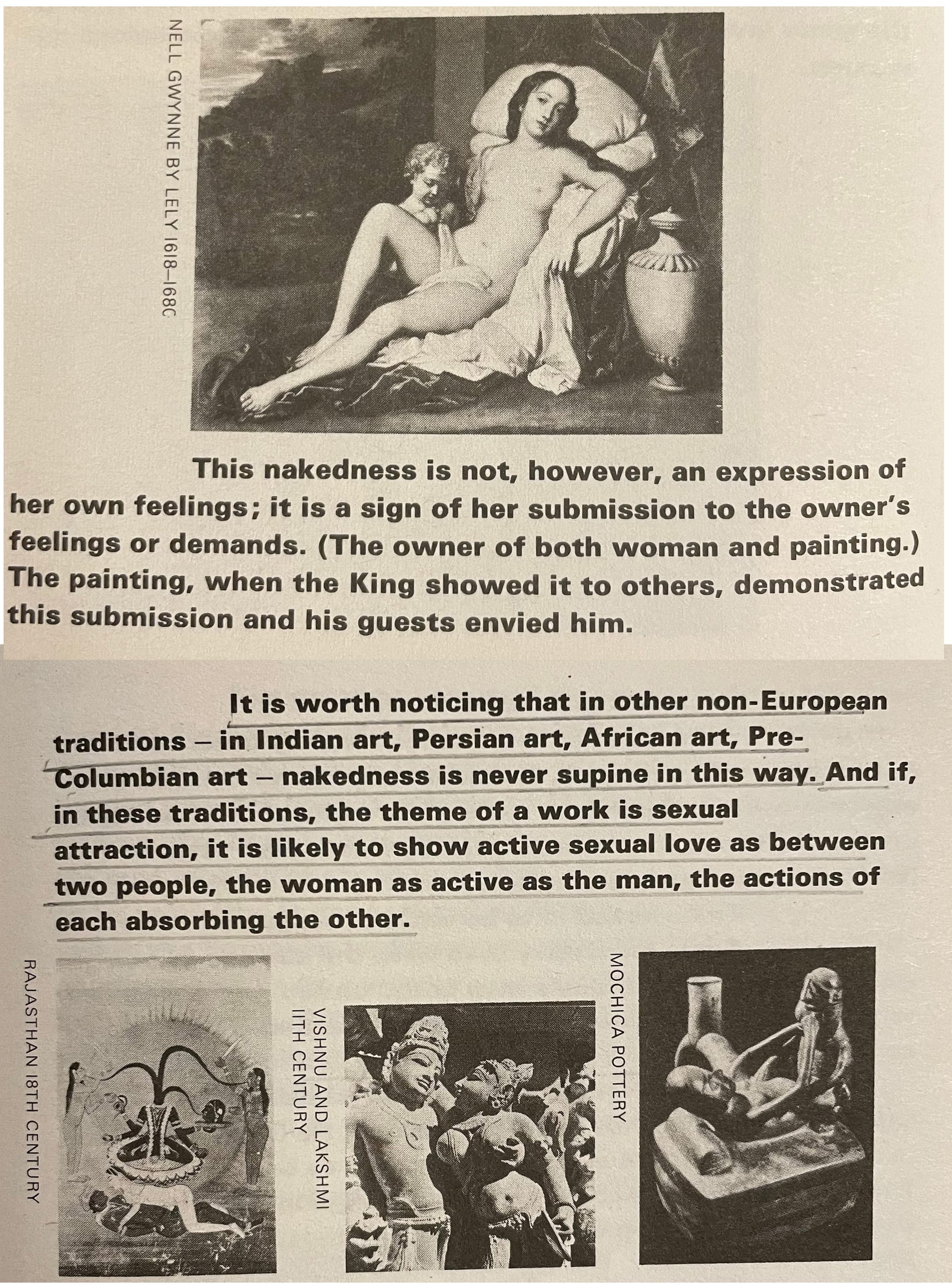

There is this interesting book by John Berger: Ways of Seeing. It is a collection based on a BBC series of the same name from the 1970s. Although some parts have aged, I still find it valuable overall.

«Our principal aim ha been to start a process of questioning». John Berger, Ways of Seeing. Penguin, 1972.

«But the essential way of seeing women, the essential use to which their images are put, has not changed. Women are depicted in a quite different way from men - not because the feminine is different from the masculine - but because the ‘ideal’ spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman, is designed to flatter him». John Berger, Ways of Seeing. Penguin, 1972.

Greater awareness and the fact that men are no longer the sole and greatest consumers of images have led to changes in the forty-plus year old quote, I think.

«For the first time ever, images of art have become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free. They surround us in the same way as a language surrounds us […].

The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its place there is a language of images. What matters now is who uses that language for what purpose». John Berger, Ways of Seeing. Penguin, 1972.

When we take photos, our minds tend to apply stereotypes that we've learned over time. Stereotypes are a natural part of how we understand and communicate with the world, so it's impossible to remove them completely. However, we can control and manage them by being aware of who is using them and why.

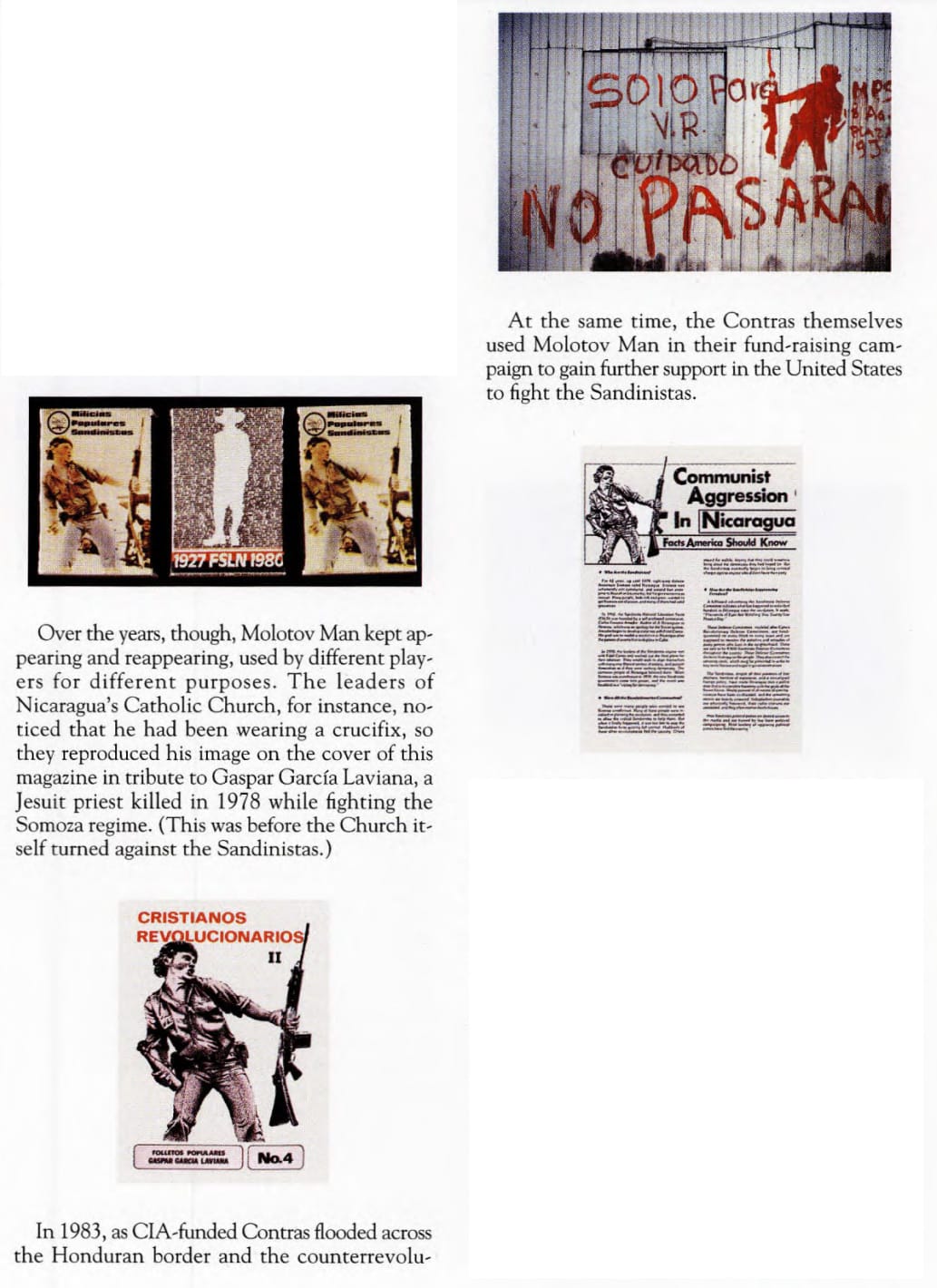

On the rights of Molotov Man, Appropriation and the art of context, by Joy Garnett and Susan Meiselas, discusses the topics of photography, appropriation, symbols, and context. However, while reading it, I couldn't help but think about how the Molotov Man became a stereotype of a combatant in our culture, despite the fact that the person who generated the photograph was very different from the stereotype. This stereotype has continued to exist in various contexts even today.

«In 1990, I returned to Nicaragua with two filmmakers to document what had happened to the people in my earlier photographs. I learned that “Molotov Man” was Pablo Arauz, who was known as “Bareta” during the war, still identified himself as a Sandinista, and had ended up with a family and a pretty good job delivering lumber. (He owned his own truck)». Joy Garnett and Susan Meiselas, On the rights of Molotov Man, Appropriation and the art of context, 2007.

Stereotypes have a tendency to uphold the status quo. It is challenging to analyze them because by doing so, we may uncover unpleasant truths. Often in photography, we simply replicate these preconceived notions that we have in our minds, just like in the typographic technique from which the term "cliché" originates. Trying to be "creative" is not enough. The solution, as with many other disciplines, lies in hard work and practice.

«In Hokusai (1760-1849) I found, "From the age of six I had a mania for drawing. Around the age of fifty I had published an infinite number of drawings, but anything I had done before the age of seventy-three is not worthy to be talked about. Around the age of seventy-three or so I understood something of the true nature of animals, herbs, fish, and insects. Consequently at eighty I will still have made progress, at ninety I will penetrate the mystery of things, and when I am a hundred and ten all my things, even a simple line or dot, will be living things"». Gottfried Benn, Aging as a Problem for Artists.