#EN2.5 The convenient economy of the identical - part I

Maps and organized information.

The brain is an organ that generates senses, information without a structure is meaningless. I won’t delve into the extensive textbook on neuroscience and neuroanatomy (it weighs 3 kg) but I’ll try to simplify things for you.

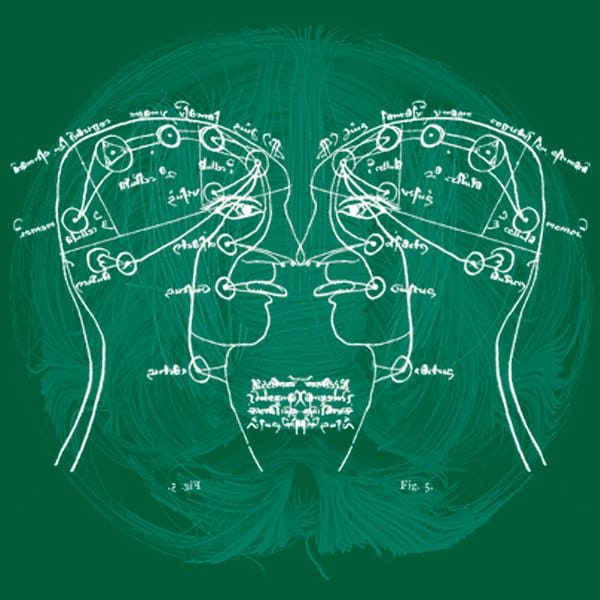

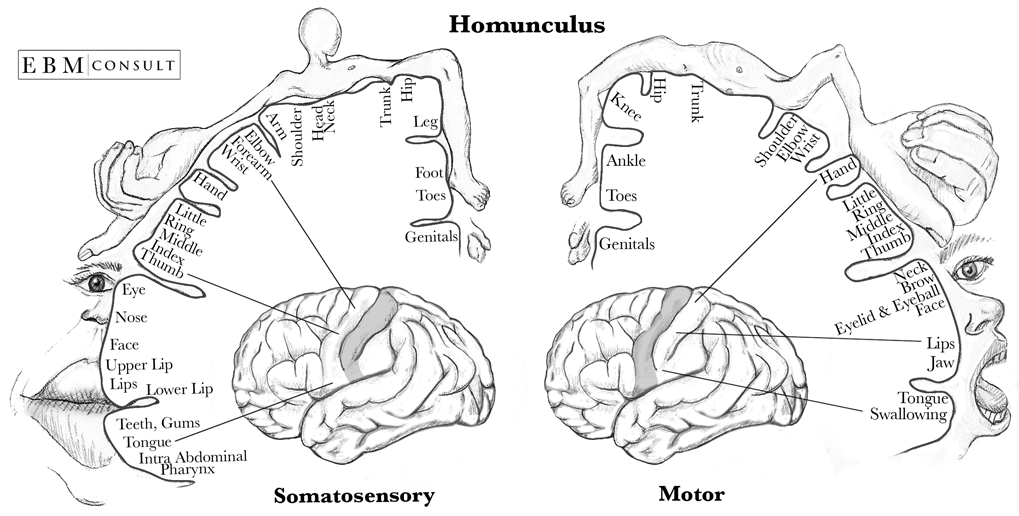

The neocortex, the youngest and largest part of our brain, is responsible for constructing meaning based on the inputs it receives. It is a relatively thin tissue, only a few millimeters thick, but stretched out it covers an area of 2600 square centimeters, which is equivalent to about four sheets of A4 printer paper placed close together. The neocortex is densely packed with neurons and glial cells (the functioning of the latter we still don’t fully understand: for a long time, glial cells were overlooked because they were thought of as the “glue” holding neurons together). The neocortex fits inside the skull by using folds and convolutions, a strategy similar to the one used by the intestines.

Researchers consider the neocortex as the center of higher cognitive functions: conscious thought, language, motor and behavior control, and more. Each part of this structure “contains” models for processing and retaining information, as well as interpreting reality.

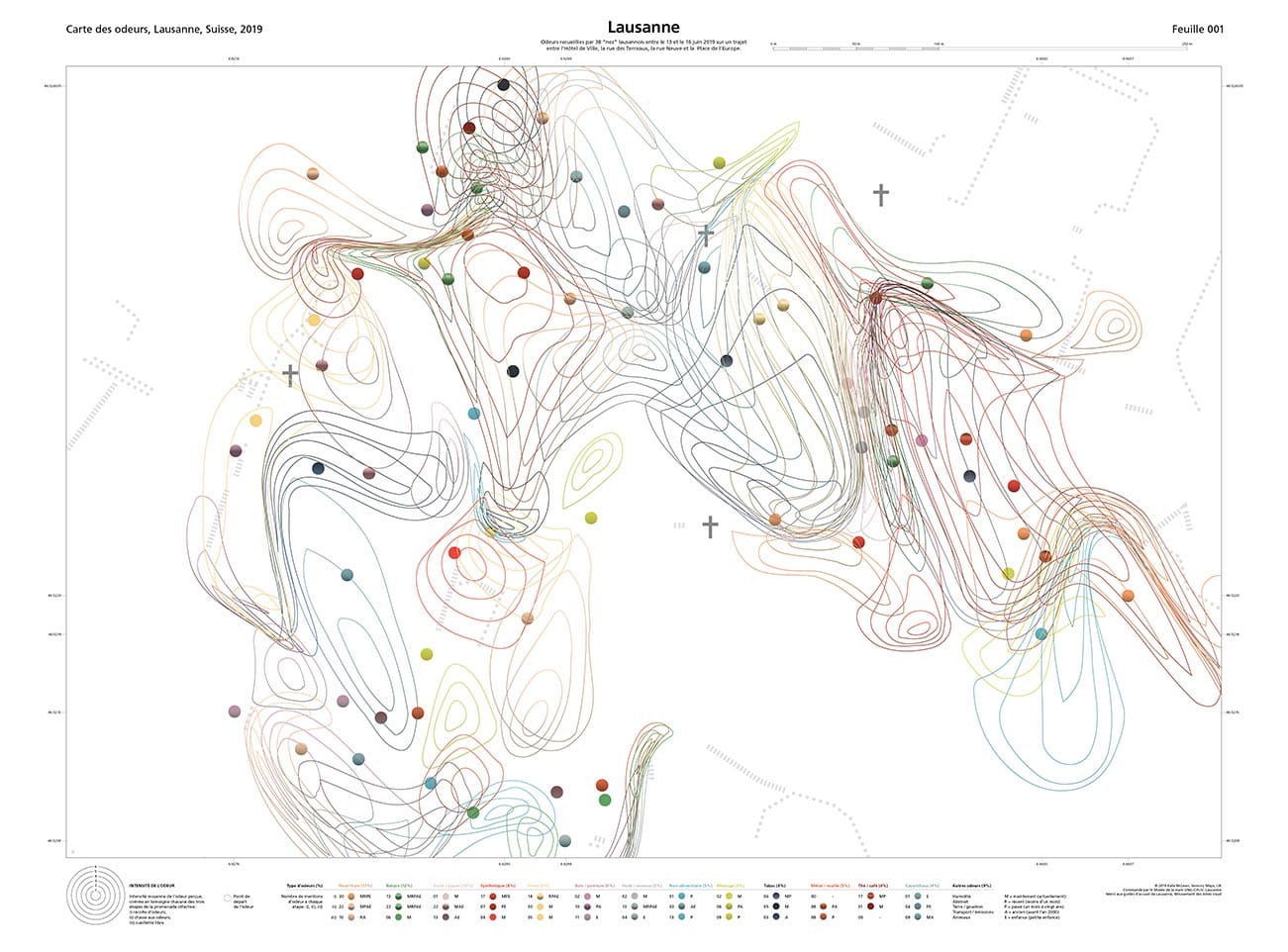

Even at the biological level, our senses and systems are organized to collect and transmit information as efficiently and economically as possible. When we smell something, our olfactory neurons don’t record and send all the chemical molecules they perceive to the brain. Instead, they are activated by forming “maps” that represent enough information to distinguish something disgusting from something appetizing.

Collecting and storing all the information in which we are immersed is not biologically possible or even useful.

«When you collect everything, you understand nothing». Edward Snowden.

Maps, models, and patterns are all tools we use to understand and orient ourselves in the world. Stereotypes as schemas, are tools that allow us to categorize all social experiences, people, and behaviors to act accordingly.

Stereotypes are patterns of people or groups that exist and persist because they serve specific cognitive, social, and expressive functions. They are tools that our minds use to save processing and memory resources, optimize behavior, speed up communication, and fill in ambiguous information. While practical, stereotypes can also create exaggerated caricatures. They are practical because they are conservative, cost-effective, and generalizable. However, they can be harmful because they are conservative, cost-effective, and not specific enough.

«“The map is not the territory” is a phrase coined by the Polish-American philosopher and engineer Alfred Korzybski. He used it to convey the fact that people often confuse models of reality with reality itself.

According to Korzybski, models stand to represent things, but they are not identical to those things. Even at their best, models require interpretation. They are imperfect because they are, by definition, an abstraction of some larger complexity. Furthermore, we often misunderstand their limitations, preferring an incorrect model to no model at all. It’s human nature». Mark Bessoudo, The map is not the territory. (The Art and Science of) The Possible, 2019.

Models and maps are simplifications and therefore have their limitations. We tend to trust the tools we use without questioning their validity and reliability, especially those that are always present in our lives and seem to work automatically. This trust is justified because these tools generally work and make sense to us, based on our personal and cultural interpretations. However, it’s important to remember that the sense we attribute to them is not an objective quality like mass or length.

«Cultural interpretation is an ongoing, always incomplete process, and no one gets the final word». Susan Bordo, The Male Body. A New look at Men in Public and in Private. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

The way we understand the map can be connected to networks of practices, institutions, and technologies that uphold positions of power and control in specific areas. When we discuss stereotypes and prejudice, we often think of extreme patterns and attitudes. However, we should not only consider repressive power but also constitutive power, which shapes and promotes what we desire and perceive as normal or unacceptable, rather than suppressing it.

«The rules for femininity have come to be culturally transmitted more and more through standardized visual images. Femininity itself has come to be largely a matter of constructing the appropriate surface presentation of the self». Susan Bordo, Unbearable Weight. Feminism, Western Culture and the Body. The Regents of the University of California, 2003.

The last two quotes are from somewhat old essays, but I still find Susan Bordo’s ideas clear and relevant, even when considering the complexities that have arisen in recent times. So, have these complexities developed over time, or have they always existed, and we simply didn’t see them because we were using inadequate maps?

There are numerous methods to enhance the detail of a map, and art is one of them.

«[...] a battle with language to make it the language of things, which starts from things and comes back to us laden with all the human we have invested in things [...]. The word is what is needed to account for the infinite variety of these irregular and minutely complicated forms». Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium.

In the past, when I was taking photographs, I often found myself questioning the purpose and significance of my work. It felt like a way to maintain a sense of control and measure whether I was on the right track or not. It provided reassurance during times when I felt unsure of myself.

It’s not a wrong approach at all. In many cases, such as commercial photography, it’s important to ensure that what you’re creating meets your (or the client’s) expectations and goals. However, the crux of the matter here is that when we use photography to create a product (such as a photo shoot, a portrait, or an exhibition), we are following a model or prototype that is generally agreed upon and defined, which is also influenced by the art market and industry.

There is a distinction between “photography” and “photography” as a tool for research and exploration. In the latter case, models or goals may not be immediately crystal clear. We can think of it as a blend of different sources of inspiration and energies, like an alchemical potion. It’s not always possible to question the purpose of our actions because the purpose is still being formed. This process can be disorienting because it disrupts conventional thinking. Photography in this sense is used to challenge and transform, to chart new territories, and to create something that is seeking expression.

«The mental plane’s genesis originates from how the photographer mentally organizes the image. When taking photographs, photographers follow mental models that result from intuition, conditioning, and understanding of reality.

The model can be seen as both rigid and flexible. On one hand, it can be rigid and limited by conditioning, where a photographer only recognizes subjects that fit the model well or builds images based on this model. This is like a mental filter that only lets sunsets through. On the other hand, the model can also be fluid and adaptable, capable of taking in and adjusting to new perceptions.

For most photographers, the model operates at an unconscious level. However, the photographer can bring the model to the forefront and exert control over it, as well as the mental plane of the photograph». Stephen Shore, The Nature of Photographs

Being able to focus and control one’s mental patterns in practice can be...messy. Patterns are comfortable; they work. Stereotypes are resilient because they give the impression that they work, provide security, are socially confirmed, and are reinforced. Social influence is an important force that sometimes affects us more than we would like. Stereotypes are inexpensive. By nature, our minds are verificationist, preferring to confirm what they already know rather than invest energy in denying it.

«In the perceptual act of looking at a portrait we recognize the human figure. This simple process of recognition results in pleasure.

[...] Thus, recognizing something is a return to something already known, a pleasure already experienced before. Sigmund Freud identified the “compulsion to repeat” as an unconscious mechanism that in repetition brings pleasure to individuals. He showed, several times, how pleasure is hidden in repetition. [...] he theorized that this pleasure in repetition can be partly justified by the impulse to master the original experience, but that repeating something known also offers a kind of pleasure understood as the “short-circuiting” of thought, as the insurance of the same.

[...] The pleasure consists in repeatedly seeing what is familiar and what is known (familiar or known representations - famous or infamous) [...]. Those who are seen as unfamiliar struggle to be represented or consider that they have been represented in ways that do not fit or correspond with their self-image. Of great value is the work of photographers who are conscious of representing the unrepresented in new ways, relating it in some way to the actual identities of the models-and this is where we often get innovations in portraiture, precisely because they interrupt the comfortable economy of the identical». David Bate, Photography: The Key Concepts.

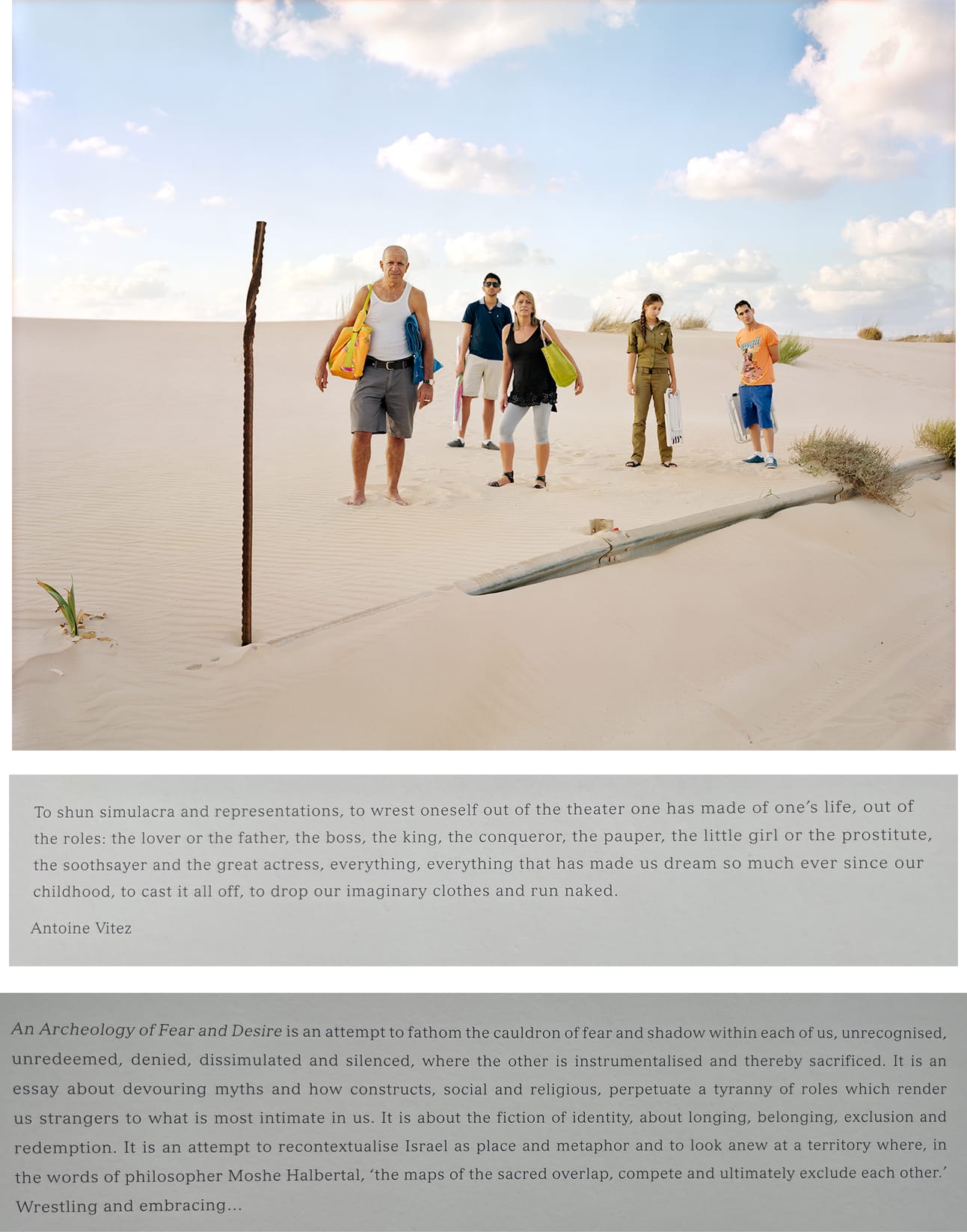

Visual language can flatten what is in front of us within a category, creating grotesque caricatures, even passing as innocuous, that become part of our culture.

But photography can also add specificity and depth.

«Arbus’ photographs confront the viewers with their own prejudices and preconceptions – this is the spirit of “evil” pervading her work. Who are they to deny certain people the right to be seen or respected?

One might argue that Arbus’ photography could have been less intrusive, and that her work is an example of morbid fascination masquerading as art. However, I believe there is an acceptable motivation behind her style. Described as “a little cold, a little harsh” by herself, Arbus’ photographs follow the advice of her tutor, Lisette Model: the more specific you are in a photograph, the more general its appeal will be». Sophie Holloway, Diane Arbus: Looking Evil in the Eye. Varsity, 2021

«But there is arguably a difference between Arbus’s early fascination with trans identities as a visual shorthand for deceit, surprise, and transgression and the approaches taken by the post-gay liberation work of Bowers and Errázuriz. They do not rely on titles to invert assumptions about how clothes, hair, and posture might or might not securely “match” an underlying body. Rather, they grasp that one promise of portrait photography is that it can particularize, that it can give us some access, however compromised, to the individual details of the person». Julia Bryan-Wilson, On Feminism, Beyond Binary. Aperture, 2016.

But to add detail, one must make the effort, employing energy to explore the territory from the maps we already have, to adjust them, and to point out new paths and possibilities.

Can this be exhausting? Yes.

We exist within a system driven by outward-focused emotional exchanges, where opportunities for introspection have been overshadowed by the desire for external recognition and validation. The journey of photography is fraught with such challenges. It requires a continuous recalibration of the equilibrium between our internal aspirations and external appreciation.

Photographers, in a sense, are like explorers. Whether it’s a landscape, a person, or an object, we can think of it as a kind of territory. It may be unexplored or already known, accessible or unreachable. Not everything has to be the ultimate destination of a journey.

«Life isn’t perfect, but then photography isn’t either. Indeed photography’s imperfections are becoming all too familiar. Often now we hear that there are too many photographs, that we are buried in them. Growing accustomed to the burden of this accumulation has made it difficult to imagine what photographs we might still need […].

To make a photograph the photographer must be in the presence of the subject. This is true even in the special case where the subject is an arrangement in the studio, or simply another photograph. In the more general case it is not only true but enormously consequent. To photograph on the top of the mountain one must climb it; to photograph the fighting one must get to the front; to photograph in the home one must be invited inside». Peter Galassi, Pleasures and terrors of domestic comfort. MoMa, 1991.

But what happens when the explorer only has access to distorted maps? How do we avoid becoming entangled in our stereotypes and keep following already charted paths that only keep us going in circles?

We’ll definitely dive deeper into this topic in the next article, in late June. But for now, we’ve already covered quite a bit of ground.