#EN2.6 The convenient economy of the identical - part II

Maps and organized information.

In this article we continue the discussion we started in May:

Photographers, in a sense, are like explorers. Whether it’s a landscape, a person, or an object, we can think of it as a territory. It may be unexplored or already known, accessible or unreachable. Not everything has to be the ultimate destination of a journey.

«Life isn’t perfect, but then photography isn’t either. Indeed photography’s imperfections are becoming all too familiar. Often now we hear that there are too many photographs, that we are buried in them. Growing accustomed to the burden of this accumulation has made it difficult to imagine what photographs we might still need […].

To make a photograph the photographer must be in the presence of the subject. This is true even in the special case where the subject is an arrangement in the studio, or simply another photograph. In the more general case it is not only true but enormously consequent. To photograph on the top of the mountain one must climb it; to photograph the fighting one must get to the front; to photograph in the home one must be invited inside». Peter Galassi, Pleasures and terrors of domestic comfort. MoMa, 1991.

We’ve got some unanswered questions from here on out. What happens when the explorer only has access to distorted maps? How do we avoid becoming entangled in our stereotypes and paths that only keep us going in circles?

Let’s face it, our first take on a new subject is always influenced by our existing thoughts. Just hearing about something isn’t enough to break down stereotypes. There’s a big difference between thinking we get something when it’s explained to us, and experiencing it ourselves. The first impressions or photos will always carry some of our old views before showing the new ones. They might still hint at what we don’t like, fear, don’t understand, or feel distant from.

Sometimes I find it very challenging to take photos from these dilapidated structures and points of view. However, I also think it’s important to acknowledge and understand the limitations of our tools. Another significant step that greatly helped me came from theater and writing, particularly discussing stereotypes and archetypes.

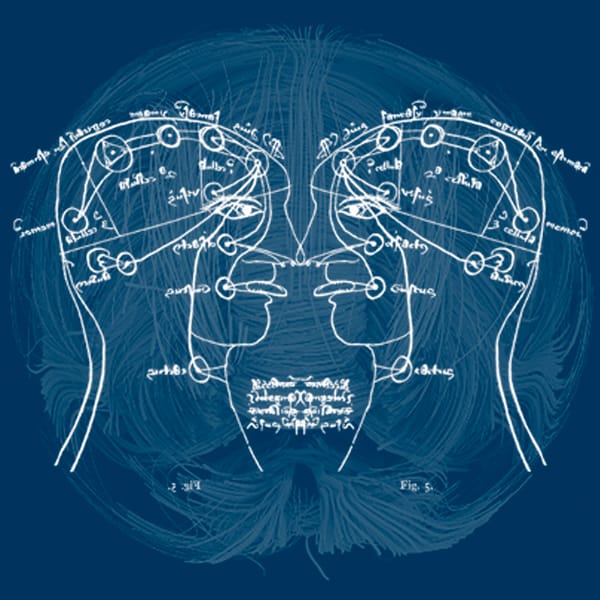

In psychology, stereotypes are patterns of individuals, groups, and behaviors that we learn throughout our lives, strongly influenced by the culture and society to which they belong. Archetypes are general forms of social representations that stem from the universal human experience across different cultures and historical eras. We can compare archetypes to biological processes (hunger, thirst, sleep, etc.) but applied to the mind (I’m oversimplifying the discourse).

The topic is quite complex and fascinating, and there are plenty of resources available on Jungian archetypes, which mainly focus on a number of types. Jung’s discussion can be a bit more complex, but we tend to categorize, so I encourage you to do your research.

Stereotypes are organized structures of information. When used in photography or narrative without being questioned, they create one-dimensional images.

Some of the bad conceptual photos and a few stock images are just terrible, but they’re also super interesting to study because they perfectly capture the stereotypical concepts they represent, and it’s so obvious.

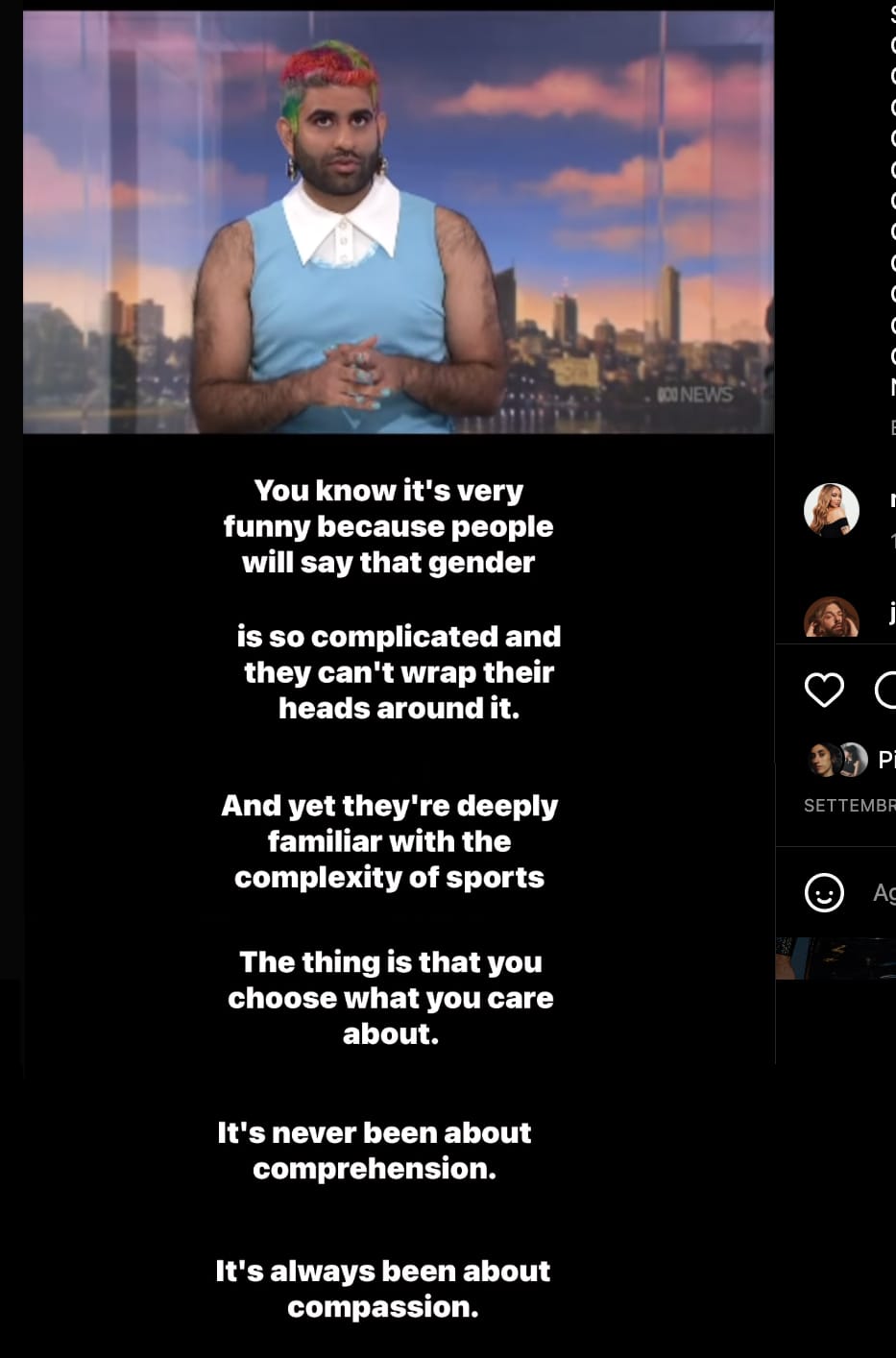

Sometimes stereotypes are not always obvious and can be hidden in attempts to make representation more inclusive. This is evident in many TV series and films that include secondary characters from minority groups. It seems like they are included to “check a box” or follow a trend, without any real effort to explore the uniqueness of each individual.

«Is the media industry really about inclusion or is it just a symbolic gesture?

Tokenism is a stale theme that has existed in the media industry for decades. Tokenism is defined as “the policy and practice of making a perfunctory gesture toward the inclusion of members of minority groups”». Georgia Bates, Fake Inclusion and Tokenism in the Media Industry. Injection, 2021.

The issue is not limited to just the media and visual language. Culture reflects and is interwoven with society and everyday life.

«“Stereotyping is a perfectly legitimate technique to use,” Glover says. “But only for initially sorting information about people we encounter”». BJ Glover, We’re So Fake About Diversity and Inclusion. TLNT, 2020.

Stereotypes stick around and pictures can lie, but these aren’t impossible problems. Deception sticks around as long as there’s no real interest in including everyone.

«Perhaps the most troubling aspect of fake diversity-whether a manipulated photograph or a political organization that presents a glib version of non-white inclusion - is that it’s deeply cynical. [...], count on us to be easily satisfied by fake diversity, count on us not to care what's behind the superficial images with which we’re presented. They think they can engage in racial capitalism and get away with it - that they can extract value from non-white identity without anyone even examining the legitimacy of that non-white identity». Nancy Leong, Fake Diversity and Racial Capitalism.

Sometimes the issue of representation cannot be solely attributed to photography. It is a problem deeply ingrained in many aspects of our society for centuries, particularly in positions of power and decision-making. Images mirror the existing reality.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t work on it, and things might be different tomorrow.

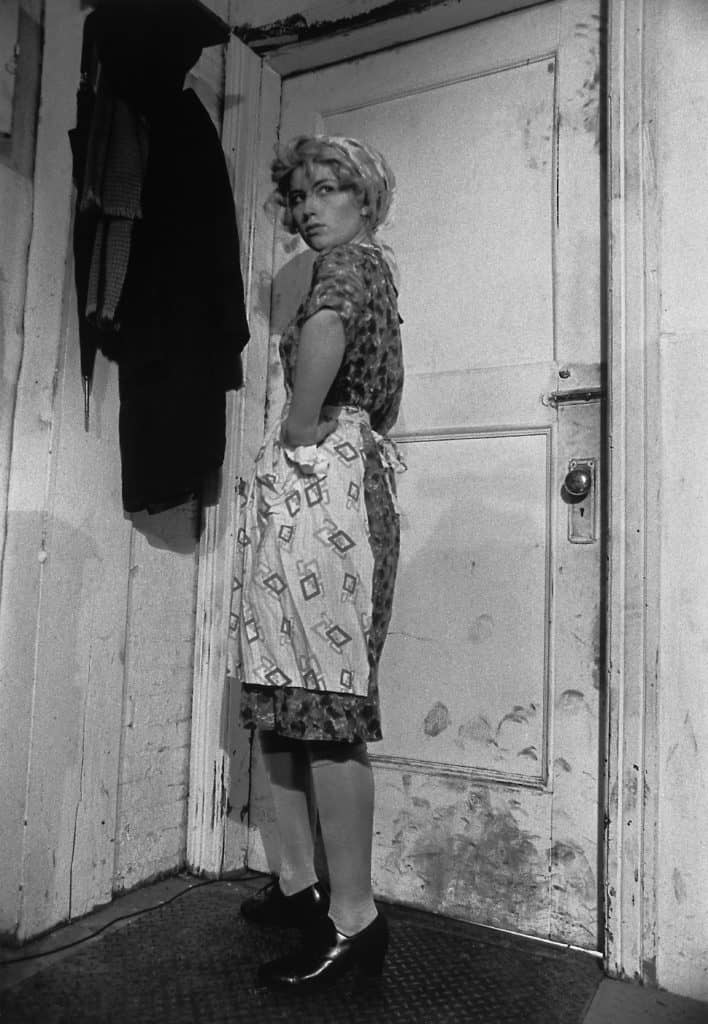

If the stereotype is the overly rigid container, the archetype is the instrument of possibilities. In Untitled Film Stills, Cindy Sherman relies on the archetype to construct the various scenes.

«The first, inevitable reaction to Untitled Film Stills is a sense of déjà vu. ‘I have seen this film before!’ the viewer is bound to think. However, he certainly has not. The artist, in fact, alluded to genres without referencing any recognizable film and, yet, every element - framing, costumes, facial expressions, and so forth - is so embedded in the collective memory that it arouses a sense of familiarity. In this regard, acclaimed art historian Rosalind Krauss has described Untitled Film Stills as ‘copies without originals’». Benedetta Ricci, Portraits of America: Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. Artland Magazine.

The archetype is only a starting point, never an endpoint or a tool for making judgments. Derivatives of the same archetype will share similarities but will always be distinct and recognizable, with their unique identity. Derivatives of a stereotype will always appear identical, even when they differ in physical and aesthetic characteristics.

In a story, you can have stereotypes and archetypes at the same time. Stereotypes are like the stuff that’s in the background, things that the writer doesn’t want to talk about in detail. The archetype is what leads to the main ideas that are developed in the story.

A simple example that comes to my mind comes from the world of video games. The main characters are carefully designed, while the “enemies” often have a standard appearance. Occasionally, they are altered just enough to indicate when they are particularly challenging to overcome.

In any narrative, “the other”, is often portrayed simplistically to highlight the main character.

Narratives and power are always intertwined. Prevalent representations create adherence because we are accustomed to seeing them around a certain discourse. Often, we may not even realize that there could be alternative representations. Acknowledging the limitations of the existing models without succumbing to the comfort of uniformity is crucial. It also requires a willingness to recognize and bridge gaps, and the honesty to call things by their true names.

«What looking at the two projects side by side suggests is that unraveling stereotypes is difficult to do without first bridging certain distances: going to places, meeting people, collaborating with them or somehow embedding their perspectives in work that is about them.

In 2015, the Spanish-Belgian photographer Cristina De Middel posed herself an obvious but underasked question. In most photographic projects about sex work, it is the faces and bodies of women we see: their strength, weakness, courage and suffering. Where are the men?» Teju Cole, Photographing Past Stereotype. The New York Times Magazine, 2018.

«Prostitution has traditionally been explained by the media with photography focusing only in one half of the business. If aliens came to earth and tried to understand what prostitution is about they would believe it is a business based on naked women staying in dirty rooms.

With Gentleman’s club I tried to give visibility to that other 50%.

During June 2015, I put an advert in a newspaper in Rio de Janeiro asking for prostitutes’ clients to pose for me in exchange of money. My intention was first to see who these people were and also to invert the roles of the business, as they would be selling also part of themselves. The response was massive and this is a selection of the men who accepted the deal.

All of them were asked about their experience, personal history and motivations and this information is in the captions of the images. I have tried to publish this series in different media but there seems to be no interest (so far) in getting to understand the whole dimension of the business». Cristina de Middel, Gentleman’s Club.