#EN2.4 Vehicles of prejudice - part II

Sources of power that lie outside and inside us.

Let’s continue our conversation on stereotypes and prejudice. You can find the first part of this discussion here if you missed it:

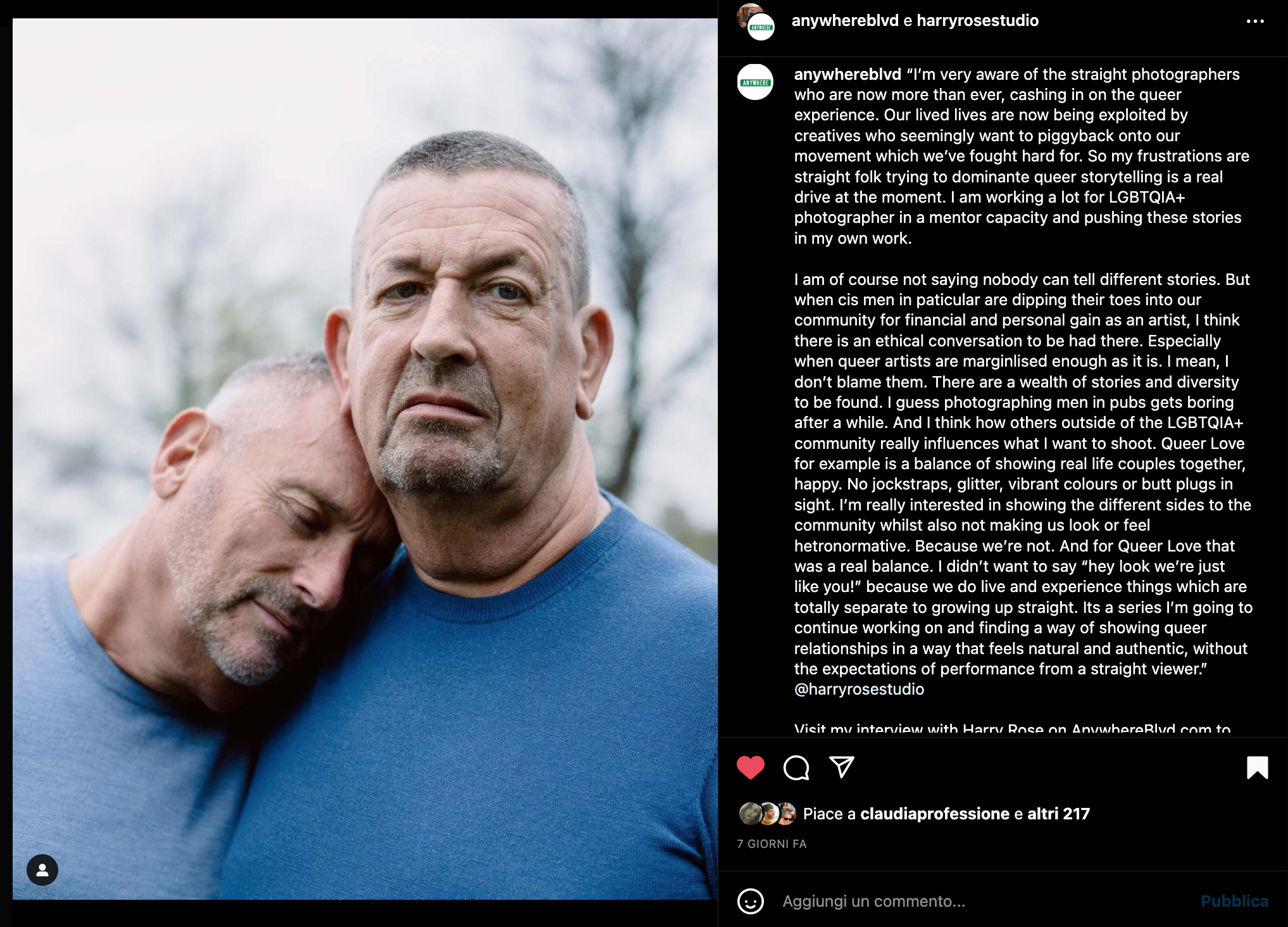

When we take photographs, we can often capture moments in places, communities, and situations (either physical, social, or psychological) that otherwise we wouldn’t have access to. We bring our own experiences and knowledge to these situations, and the images we capture represent our perspective. But what impact does our presence and the images we capture have on these spaces and communities? What traces do we leave behind?

Not all stereotypes are harmful or lead to prejudice. As photographers, we don’t necessarily have to work on socially relevant issues, but it is valuable to have a critical perspective. By understanding our backgrounds and experiences, we can create images that go beyond clichés and reflect a more nuanced view of the world. This means avoiding replicating familiar themes and stereotypes, and striving to produce unique and authentic images.

«It is important to recognize all people, especially the poor and disabled. They have the right to be seen and heard also». Mary Ellen Mark in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

If thirty years ago, this statement held, today I find it to be faltering. Not the aspect that everyone deserves to be acknowledged and heard, but the concept of who holds the right to create and convey the stories of others. In the past, official channels such as journalists, reporters, and professional photographers were the only means of gaining impactful visibility. However, times have changed drastically, and the issue of visibility has transformed in every aspect.

It is concerning to be stuck in our preconceptions and habits, but what’s worse is the false belief of having none at all. Just because we don't see our biases, it doesn’t mean they don’t exist and it’s hard to challenge something that we can’t even perceive.

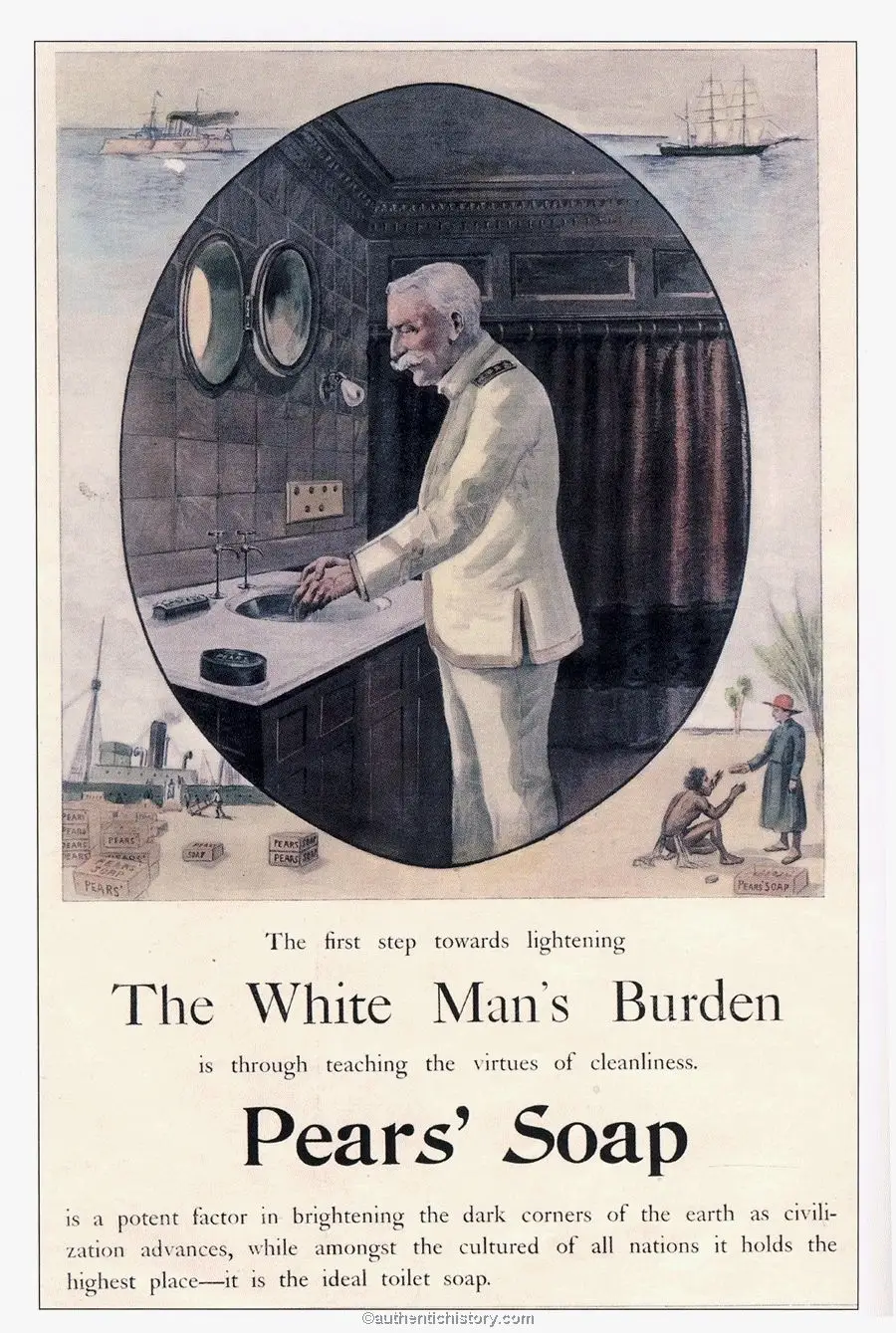

Prejudice, as an a priori negative evaluation based on a stereotype, influences how we approach that individual or group. During the early 1900s, it was common to display prejudice and assert privilege and superiority, even in everyday communication, advertisements, and propaganda.

It is rare to see communication of this kind in today’s world except in extreme propaganda or in campaigns that are deliberately launched to create a buzz. However, this does not necessarily mean that prejudice is disappearing from society. There is more awareness and more dialogue, and thankfully, the open and explicit expression of prejudice is socially sanctioned (most of the time). But many expressions of prejudice have now become hidden and almost invisible structures and mechanisms, thereby making them more insidious. Latent prejudice is rooted in the most primitive areas of the brain and is based on fear of the different, and it resists change.

In the early 20th century, governments (not just dictatorships) realized the power of photography in shaping attitudes and canons. Photography was a new, experimental medium that was free from the constraints of centuries of painting and sculpture history.

«In its infancy, photography was practiced by scientists and alchemists, not artists. A photographer didn’t have to be enrolled in the hallowed halls of the academy; she could cook it up in the kitchen». Eva Respini, On Feminism, Aperture, 2016.

Then, photography gained power and value, and a “right” and “authoritative” approach to photography emerged, as opposed to experimental and eccentric styles. This type of photography is still considered by many as the basis of education for the “True Photographer”, and it continues to propagate and reward echoes of past structures and attitudes, which were objectionable even then and are unacceptable today.

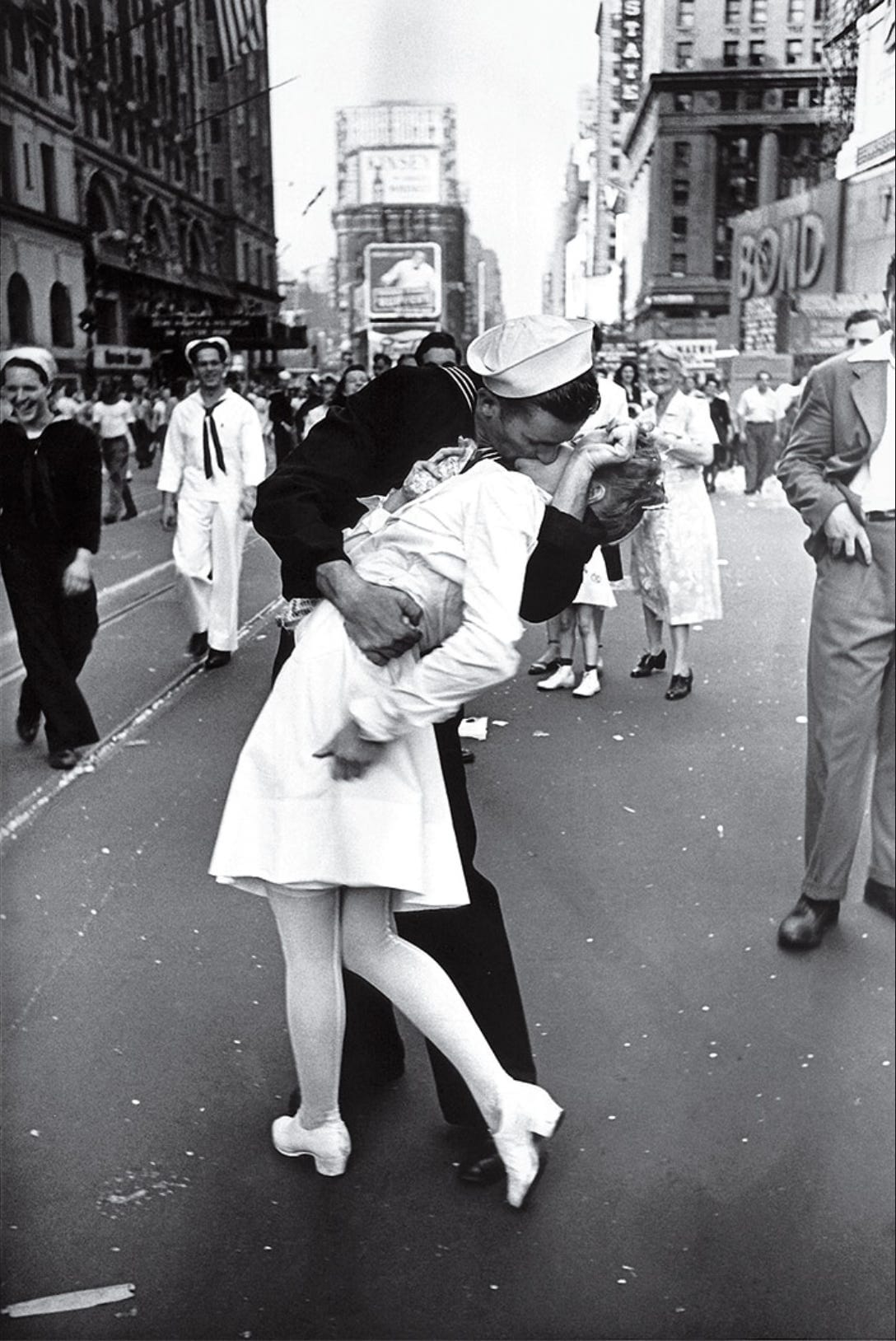

For example, consider Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day in Times Square, one of the iconic public domain photographs of the end of World War II. The photograph was published on the cover of the New York Times the following day, with the headline “Kissing the War Goodbye”.

Some people analyze the visual elements and composition of this image, and that’s all they do. They often speak of the contrast between black and white, the diagonal leg, and the capturing of the moment. They look at this picture as a sublimation of the celebrations for the end of WWII.

«All photographers have to do, is find and catch the story-telling moment». Alfred Eisenstaedt, About Photography Blog, 2020.

When I look at this picture, I see a man holding onto a girl tightly, with his fist and fingers clenched at his side and his elbow behind the back of his head. The girl appears to be off-balance, with her pelvis leaning forward and her feet pointing in a particular direction (as our bodies tend to follow the direction of our feet). One hand clutching onto something, the other hanging loosely as she moves. We don’t know for certain if she is moving up to reject the man’s kiss or coming down from a previous attempt. Nevertheless, this scenario reminds me of the passive and submissive portrayal of women in certain paintings.

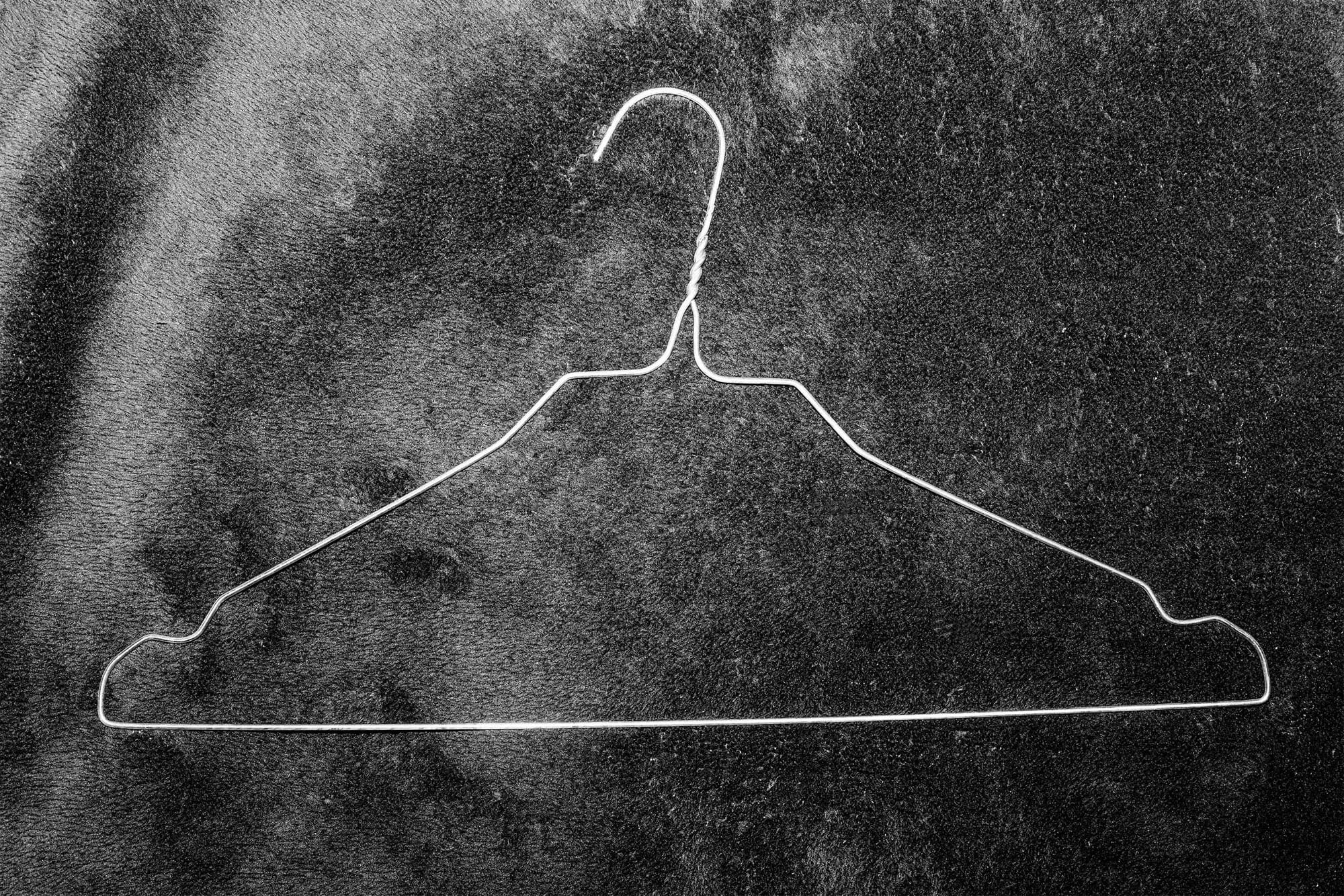

Anyone who has been kissed without consent knows how uncomfortable, painful, and suffocating it can be.

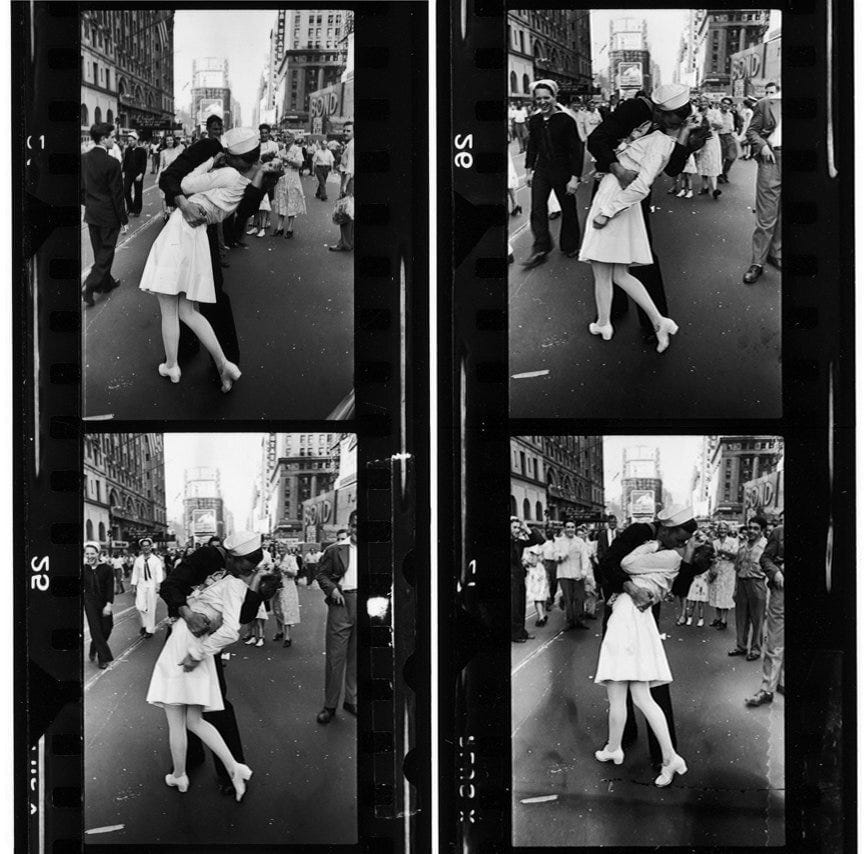

Eisenstaedt captured four frames of that moment. Since he could not use digital burst technology at the time, we can assume that the kiss lasted for at least a few moments.

After reviewing the entire sequence, it is evident to me that the nurse was attempting to move him away.

«“The excitement of the war being over, plus I had a few drinks, so when I saw the nurse I grabbed her, and I kissed her”.

[...]

“I felt he was very strong, he was just holding me tight, and I’m not sure I - about the kiss because, you know, it was just somebody really celebrating. But it wasn’t a romantic event. It was just an event of thank God the war is over kind of thing,” adding that “It wasn’t my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and kissed or grabbed me”. She said». George Mendonsa and Greta Zimmer Friedman, About Photography Blog, 2020.

The fact that the iconic photograph of the end of World War II, depicting a sailor kissing a nurse, became so popular in 1945 can be attributed to the belief that it was normal for boys to celebrate in such a way after going through the horrors of war. However, this belief is outdated and problematic, and unfortunately, even after almost 80 years, similar mentalities still exist today. Photography has the power to perpetuate stereotypes and prejudices, and can inadvertently promote problematic messages that are deeply ingrained in our society.

«But isn’t photography also a form of stupidity?» Luigi Ghirri, Lessons in Photography.

Our brains have a hard time recognizing two opposite meanings linked together (good and bad). Therefore, how can this image be problematic since it represents such an important event?

Fortunately, some photographs challenge stereotypes and make the limitations and dangers of a narrow viewpoint more visible. Let’s consider the same period in the 20th century. Weegee (Arthur Felling, originally Ascher Fellig) on assignment to document the “Perfect Baby” contests.

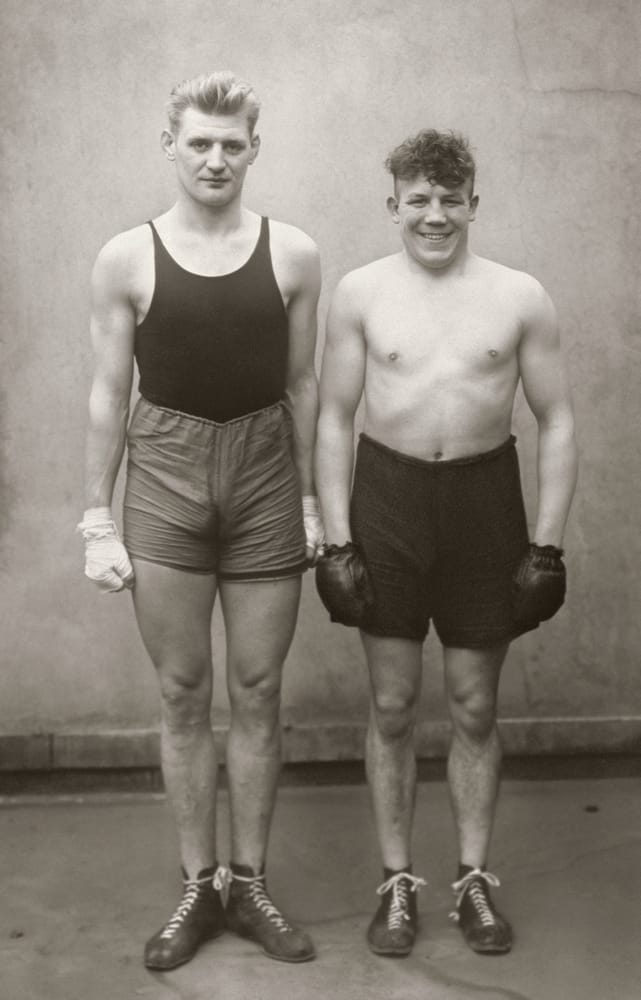

During that time, the concept of eugenics was widely accepted and discussions about breeding, improving , and selecting the perfect individual were commonplace in both Europe and the United States. Children who took part in these competitions were often photographed in a studio while posing.

«Many proponents of eugenics were in positions of authority at universities and colleges, professional organizations, museums and industry, and they gave credibility and clout to the movement, which was popularized and disseminated in newspapers and magazines, lectures, books and exhibitions.

The picture by Weegee on the following page would have offended the sensibilities of the starchy, self-important eugenicists. The winners at eugenic affairs were usually posed by local photographers using the prim conventions of studio portraiture. Frilly white dresses, spotless sailor suits, and fluffy bonnets were the preferred costumes. If naked, the child’s body was depicted as perfectly still and unperturbed. And all the children were well behaved and wore sweet expressions rather than the distorted grimace of infant distress. The point of the eugenic portrait was to convey the calm, elevated character of the “well-born,” and to advance the notion that only such superior people should reproduce». Carol Squiers in Marvin Heiferman, Photography Changes Everything. Aperture, 2012.

Weegee’s photograph portrayed children in their natural state, which contradicted the idealized propaganda of perfection. The image did not rely on sensationalism or grandiosity to convey its message. Unfortunately, the picture was ultimately rejected during that time.

«But the editors missed an opportunity to draw a link between the quest to create and judge the “perfect baby” and the growing menace of eugenics both in the U.S. and in Germany. […] Eventually, over sixty thousand Americans were subjected to involuntary sterilization in the effort to prevent a less-than-perfect baby from being born to less-than-perfect parents». Carol Squiers in Marvin Heiferman, Photography changes Everything. Aperture, 2012.

Similarly, August Sander's portraits in Germany threatened the Nazi representation of Germans as a superior race. Sander's books published between 1933 and 1934 were seized, and the negatives and plates were destroyed. Luckily, a portion of the archive was saved.

Another photographer who was subjected to confiscation, censorship, and denunciation by his government is Boris Mikhailov.

«I also started working with photography because I was very pleased with a picture I had made. It was a photo of woman holding a cigarette. The combination of woman and cigarette was a radical break from the norms of Soviet photography of that epoch: you were only supposed to show Soviet women as an ideal. If naturalism didn’t coincide with the ideal, it was simply not to be made public». Boris Mikahilov in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010

«Did you have access to international photographers’ work?

Not really. Sometimes we’d see a Cartier-Bresson or an American colour photographer, but we only got to see “normal” things, nothing that was very deep. But I understood after a while that it wasn’t important for me to look at foreign photographers’ work. They have a really strong aesthetic, which corresponded to the Western environment and technology and which, I guess, was in direct contrast with my life. In my life there is dirt, things are broken. Even the way foreign organize a picture is really clean. […] I needed to concentrate on what was real, what our life was about and to create an identity through that.

[…] I think you have to understand life, then you can take a picture. If you have a good mind, you can take a good picture. […] You need to live in the place you want to photograph to really understand it, to play with it». Boris Mikahilov in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

Mikhailov aims to construct identities that reflect reality, rather than ideals, for people and places.

«Generally I intuitively felt that photography was the field where I could express myself as a citizen and a human being». Boris Mikahilov in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

Naomi Harris avoids prejudice by suspending judgment and opening herself to new experiences.

«A sixty-year-old friend of mine invited me to a swingers party and it just cracked me up. There was an all you can eat buffet, with big hunks of meat. People would just go to town on the food and twenty minutes later disappear to the back room to have sex. When I eat steak, I unbutton my pants, but I don’t want to go and have sex. As we were leaving, they were putting the breakfast buffet out and people were standing around naked eating pastry. I was mortified. I thought the whole scene was hilarious. At first I thought, what a bunch of freaks. But since working on the project, my opinion has changed a lot. I’ve explored my own sexuality». Naomi Harris in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

It is important to choose a project that resonates with us on a personal level. By personal, I mean something that piques our interests, keeps us engaged , and encourages us to observe and learn more about the world.

«When I pick a project it has to be something where I can learn something about myself or the world around me. If I'm going to work on it for numerous years, it must excite me for a while, not just be a hot, trendy topic». Naomi Harris in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

When you enter a space or community, you become a part of it. Influence is always a two-way process. Taking photos from a distance is like studying something using samples, which may be the intended purpose. However, treating living beings like laboratory specimens is a good way to categorize them, but not to truly represent them.

«I’m always very honest with the people I photograph, whether that’s a swinger for my book or an American football player for ESPN magazine. I always tell people about my own experiences and if people ask me questions, l’Il answer them honestly. I open up a lot. At the end of the day, I’m asking my subjects for something, so I want to give something in return. The least I can do is be a decent human being. Also, I try to become part of the community as much as possible, whatever that community is. When I go to a teenage event like the Rubik’s Cube World Championships, I’ll wear jeans and sneakers. If I’m going to a sex party, I won’t dress up like a nun, but wear knee socks and put my hair in pigtails». Naomi Harris in Anne-Celine Jaeger, Image Makers. Image Takers. Thames&Hudson, 2010.

Photography can sometimes be used to express judgments in a targeted way. However, many “expository” projects lack substance because the thinking and judgment behind them are weak or simply follow what is deemed acceptable to say. It takes a strong sense of reasoning and a willingness to stand behind one’s judgment to articulate a clear position, rather than just seeking personal gain from the discussion.

At times, we may feel that we have a unique perspective that only we can see. We may feel a sense of responsibility to act upon this perspective, and we may be in a rush to express ourselves. To learn how to articulate our vision and make the intangible visible, we may look outward to seek confirmation and guidance. However, despite our good intentions, the outside world may return to us the same stereotypes and biases that we already possess within ourselves.

We exist within a complex system in which various forces coexist, but we are not always aware of them. People who are skilled in photography can see things that are not immediately clear to everyone else. They can recognize when something is important and worth capturing. This is precisely why it is important to ask ourselves questions about why certain things are so important and how they can be shared with the world. It is important to create problems and confront doubts without being afraid of shame. When we ignore social rewards, we can eradicate anything that pollutes our voice.

«We, too, feel “a vague awe” at the creative ability of the artist; we, too, fear the power of the images he forms and their mysterious capacity to elevate and disturb us. They bring us into contact with certain truths about ourselves in ways that can only be described as magical, or they deceive us as if by sorcery, but since we have been educated to speak and think of images, avoiding confrontation with precisely these kinds of effects, the only way we can explicate them consists in paying attention to the reactions (and the reports of them) of those whom we consider simple, naive, or provincial, or, in fact, in turning our attention to peoples [... ] whom fortunately anthropologists have stopped calling “primitive”. [...] the term “primitive”, however, may still retain its usefulness if we take it in connection with feelings and emotions that precede the repressive cloak provided by education in civilized cultures». David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response.