#EN1.6 Information and storytelling

Flows of nothingness and worlds full of meaning.

This post is the son of a computer engineering degree, Joan Fontcuberta’s essays, and interactive fiction1. We’ll talk about information flow, meaning, and the eternal dilemma of “there are too many images out there” that photography has been carrying around since the late 1800s2. Why make more pictures when everything has already been said and done?

Let’s consider this: is quantity the only significant factor? We can look at the issue from several perspectives. We could approach it from the point of view of photographic practice, as a philosophical discourse, or by talking about the photographic market, to mention a few examples.

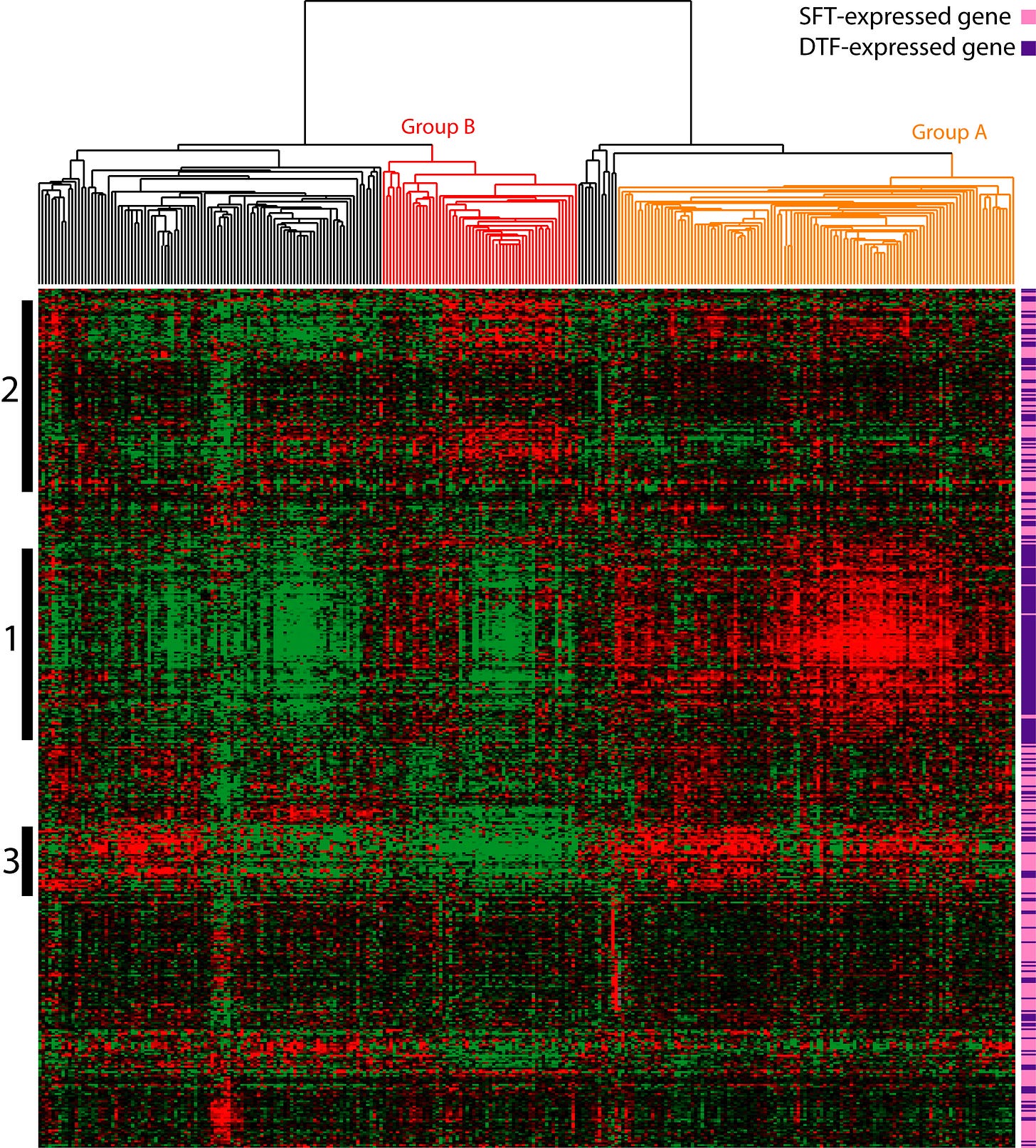

The data analysis engineer in me keeps yelling that there is no such thing as “too much information”. There’s only poorly organized information (as long as storage space is available). For my degree dissertation, I spent six months working with multidimensional arrays of genetic data. I won’t go into the technicalities of it. To cut it short, I had to run non-stop batteries of tests that needed a lot of hours of processing (if all went well).

When things didn’t go well (and the first few months, it happened a lot), a nice alarm was ready ‘o alert me at any hour to drop everything and fix the problem. And so, thanks to some 4:17 A.M. wake-up call, knocked out of bed by a damn machine ordering me to debug code, I realized I could do nothing against “too much information” except learn how to structure it.

«Images are not stored as facsimile copies of objects, or events, or words, or phrases; the brain does not encase polaroid photos of people, things, or landscapes; it does not store recorded tapes of music and speeches, or movies of episodes in our lives [...]. Throughout one’s existence, each of us acquires a flood of knowledge so that any archiving would pose insurmountable capacity problems: if the brain were likened to a library, like a library, it would soon come up short of shelves. Moreover, archiving copies usually presents not easy problems of access efficiency when they need to be found. From direct experience, we all know that when we want to recall a given object, face, or scene, we do not get an identical reproduction, but rather an interpretation, a freshly reconstructed version of the original. Moreover, versions of the same original change with the passage of years and changing experience, and none is compatible with a rigid copy representation: this is an observation that the English psychologist Frederic Bartlett made some decades ago when he was the first to argue that memory is essentially reconstructive». Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Adelphi, 2021.

This talk of mental imagery reminds me of a passage from the chapter The Post-photographic Condition:

«On the other hand, the advantage of this excess is the resulting exhaustive and immediate access to images, which thereby lose the status of luxury objects once enjoyed. Postphotography confronts us with the dematerialized image, and this prevailing nature of information without a body will make images an entity that can be transmitted and circulated in a frantic and continuous flow. According to José Luis Brea, this situation causes them to live between appearance and disappearance; to a great extent, electronic images possess the quality of mental images. They appear in places from which they disappear immediately. They are ghosts, pure specters, alien to any principle of reality"». Joan Foncuberta, The Fury of Images. Notes on post-photography. Einaudi, 2018.

Images without a physical form are electronic ghosts. These impulses linger in one place and instant as long as the source remains active, then disappear and reappear somewhere else, or perhaps not. Frigid shivers run down my spine with the slightest hard disk failure. I think about this lightness of digital information and how much it costs us to harness it in structured archives and multiple backups, always accessible but also located far away, just in case. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed.

I have recently taken up developing film and printing my own. I have discovered a different underlying feeling toward digital and analog photography. I can’t say I prefer one over the other: just tools that allow me to do marvelous things under different conditions. I see analog photography as a set of physical objects with well-defined contours which can transform and move from one state to another. Still, they remain until I (or some external event) initiate a state change.

Digital photography, on the other hand, it’s a stream that is in eternal becoming. Even if, at any given moment, it’s before my eyes, on a screen, in a specific form, I know that it can exist simultaneously in multiple different versions. Just think of how each image posted on the Internet exists at any given moment in as many slightly different versions as the devices displaying it.

And then there’s this other thing that always freaks me out when I have to start post-producing a new set of photos, which is the infinity of directions, many equivalent and still valid, that any digital negative can take with ease3. The immensity of equal choices. The endless repetition.

A print can also be declined in different ways in the darkroom, but the choices are driven more, or at least by external limits. And this working within limits makes the difficulties less frustrating (well, in my experience, as if someone is ready to take me by the hand if I need it.

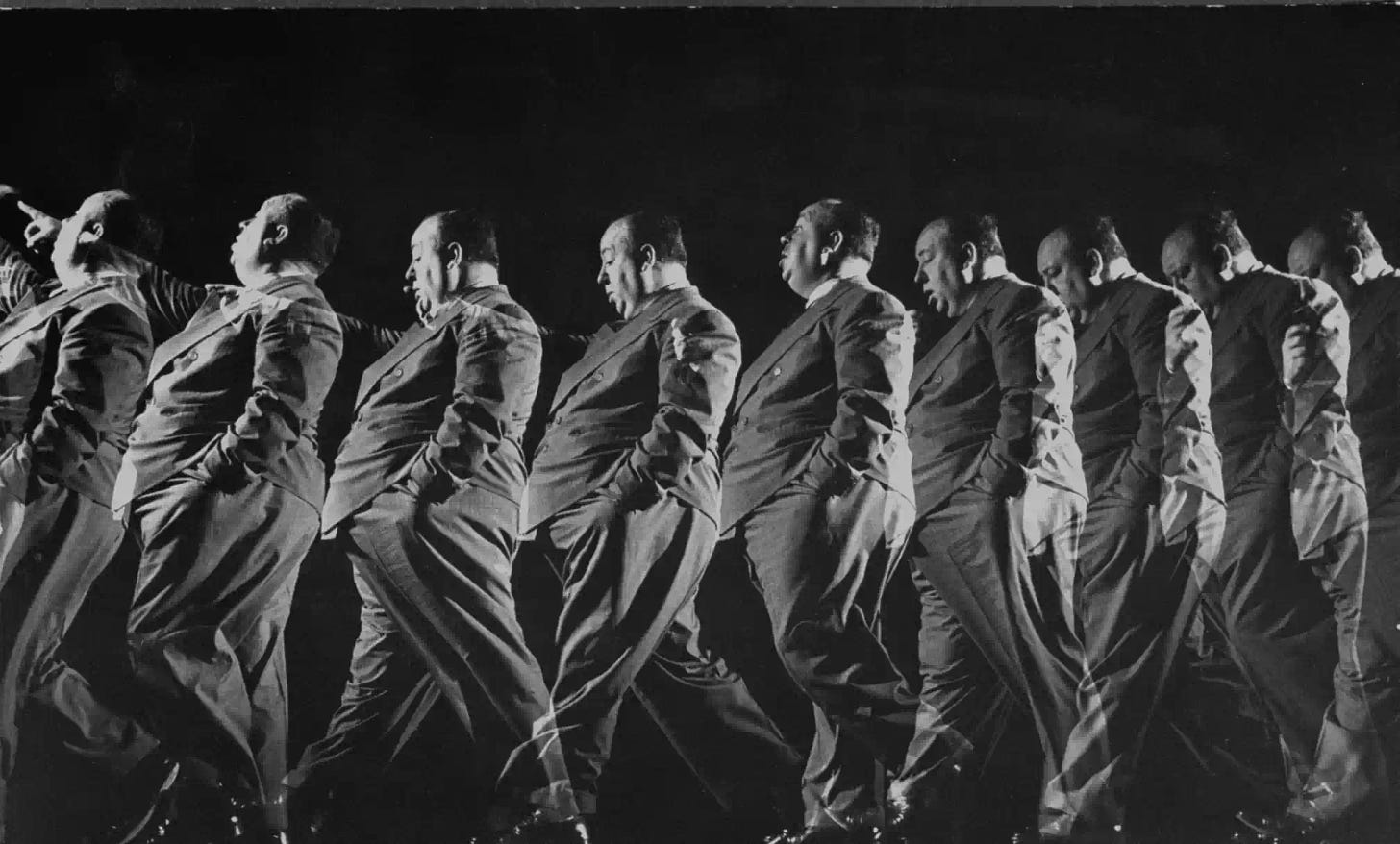

The difference between analog and digital is also reflected in how I photograph. I hardly ever set the camera in burst mode. However, still, I produce many more digital images than film, even in the same setting. In the first case, I almost feel like I’m scrolling through frames taken from portions of a video, while on the other side, I see moments, seemingly unconnected, pulled out of reality. Analog photography gives me a feeling of stability and security, like rocks emerging from the eternal flooding river of digital.

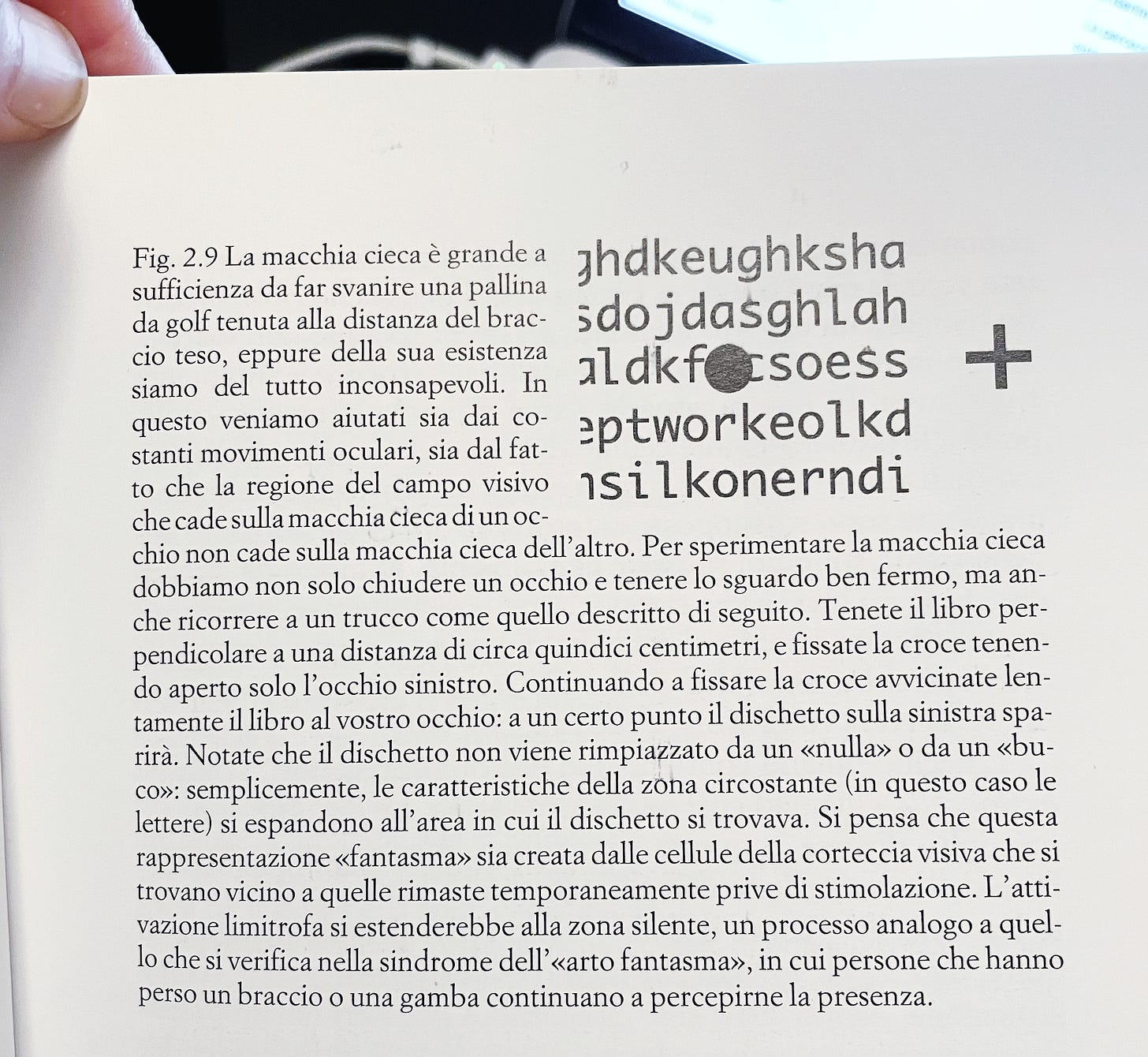

Yet, we’ve always lived immersed in information. We’re at the center of a continuous flow from outside and within us. Our perceptual system allows us to selectively shift our attention only to the portion of the information that interests us, attenuating everything else. It’s a transparent system; we’re unaware of its existence when everything runs smoothly.

Perception is not a standard feature endowed to all brains equally. It is a system composed of so many channels and circuits. Everyone perceives a reality that may be different from someone else’s.

Our perceptual system is so sophisticated and invisible that we only become aware of its existence when it begins to work differently, either more or less permanently (due to injury or aging) or temporarily (under drug effects, for example). Overall, it’s a significantly underestimated system, counting that it deals with everything that allows us to move and interact with the world.

Every mind has its particularities. Without going into too much detail, it can be said that we’ve evolved into seeing reality “roughly” all in the same way, which has a social function. Still, everyone interprets reality a little differently.

Some brains are champions at directing selective attention, almost on the level of some predators. When dogs focus one of their senses on a track, they turn off all the others. Other brains, however, always remain ready to pick up a little bit of everything, even what lies in the background. This depends on genetic and biological characteristics but is also related to experience, which modifies neural pathways. Perceptual abilities vary and are also influenced by social factors or temporary conditions.

Around the 1940s, a group of American psychologists, the New Look on Perception, had even gone so far as to hypothesize that those with a substantial prejudice against something or someone also fail to perceive characteristics that do not fit the stereotype they have in mind. There is none so deaf as those who will not hear.

«The main purpose of this movement was to introduce into the study of perception as independent variables also motivational, and more generally personological, and social factors, from norms and values to group issues. The name, New Look on Perception, was given to the movement by David Krech (1949-50). The target was the “old” point of view (old look), with reference, especially to Gestaltists, who excluded in the perceptual process the intervention of any factor other than those self-organizing factors peculiar to the dynamics of the perceptual field». Riccardo Luccio, History of psychology: an introduction. Kindle edition.

Information is a meaningless flow. Everyone interprets reality differently, and there are too many pictures around. As a creator and consumer of images, where is the value? When the whole world is on fire, what is the point of all the time I spend every day on visual information? Money and fame are not the answer.

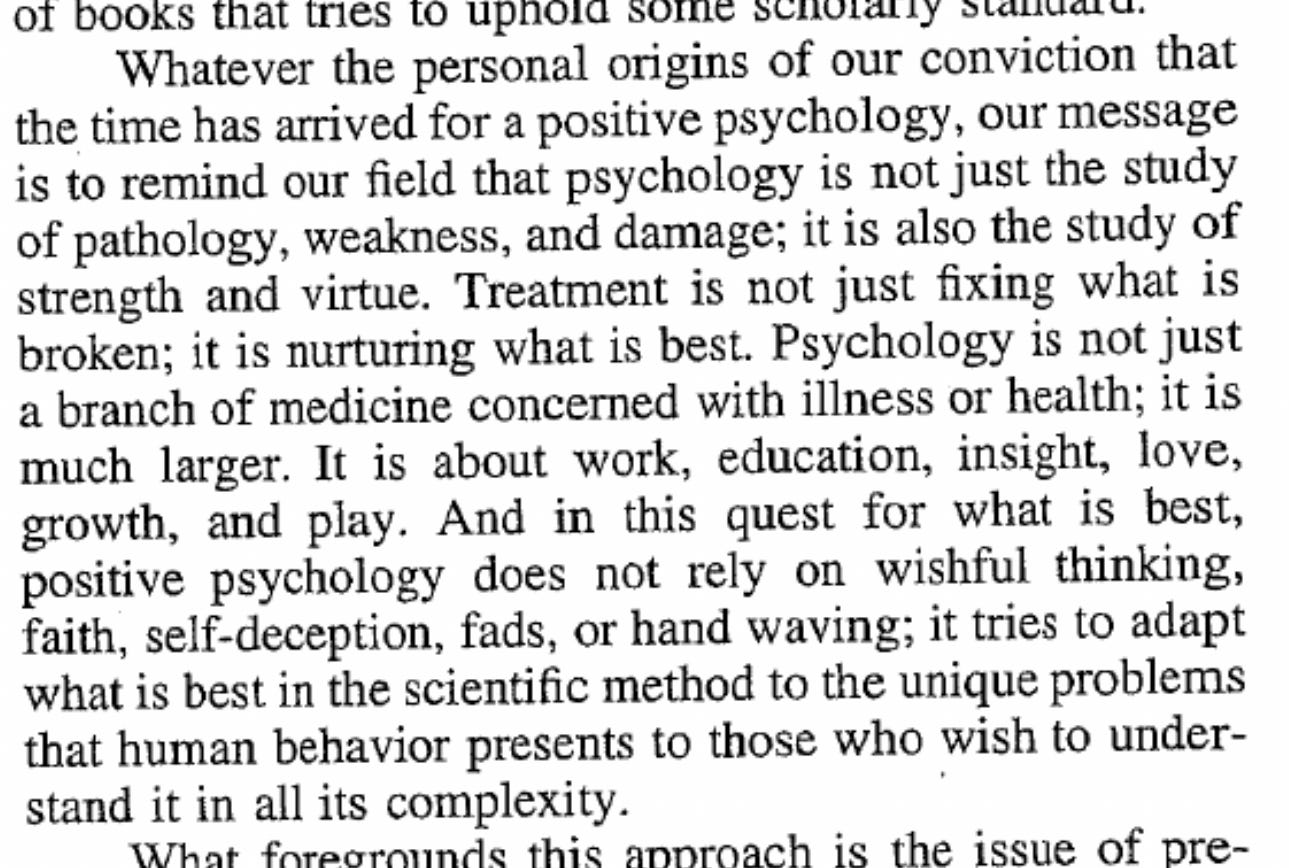

In the 1960s, psychologist Martin Seligman studied clinical depression and mental illnesses. He devised an experiment on learned helplessness involving dogs and electric shocks, with an ethical approach only possible in those years. Learned helplessness theory affirms that prolonged and repeated feelings of lack of control can lead to depression and apathy. But these batteries of experiments also led to an unexpected result that went in the opposite direction. Nearly one-third of the dogs didn’t succumb to helplessness. Despite everything, there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

This observation led Seligman to try to understand what factors prevented some individuals from succumbing to depression, which preserved their sense of self-efficacy, which stimulated resilience. A new approach, positive psychology, was born. This may sound like one of the worst pamphlets wallowing among the self-help books on service station shelves in the middle of nowhere. That’s not it. Positive psychology studies everything that helps individuals and communities grow and make life worth living, not just endure or survive.

Positive psychology researches preventive mental health factors and applied solutions to improve the quality of life. One of its goals it’s to find psychological “buffers” or niches to absorb adverse events to strengthen the mind’s immune system. Today the horrible is in the air, and these speeches of twenty years ago seem to be dissolving in the wind. Yet they are the kind of flickering light that points the way in the darkest darkness, and sometimes it’s the first thing you need to start making your way in the dark.

«The endless multiplication of photographs that capture only the outside of life may contribute to the end of the world. But some photographers, great in this, try to save it». Yves Bonnefoy, Poesia e Fotografia (Poetry and Photography). O Barra O Edizioni, 2015.

Photography is powerful because it allows us, among other things, to construct stories. Our whole world is woven of narratives that we keep producing like so many Penelopes weaving a web by day to take it apart by night, and in this constant making and unmaking is the hope and strength of being able to stay true to ourselves. Stories hold us up and define our identities. If stolen from us, we have the right to claim them, rewrite them, and play with time.

«Images of something that has not yet happened - and indeed may never happen - are no different in nature than images of something that has already happened. They constitute the memory of a possible future rather than of a past that was». Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Adelphi, 2021.

In many cases, people with dementia who can express their own version of their stories, even if mixing and forgetting events that happened, have a better quality of life.

We constantly live with the FOMO feeling of being immersed in stories and missing something every second. This is not true: we are immersed in the flow of information, and information and narrative are two different things. Information is not communication. Information itself is meaningless; it is raw material without structure.

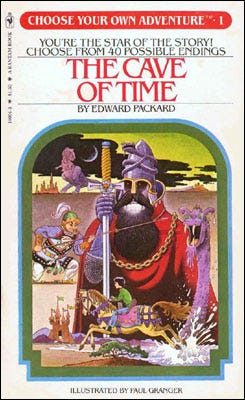

Remember the interactive books at the beginning of the post, the “Choose your own adventure” stories? When read in sequence, like regular fiction, they are not stories. It would be like looking at a bunch of photographs piled up.

We are inundated with images, it’s true. But stories, those will never be enough. We need them to grow, surpass our cultures’ limits, and heal our communities.

Information saturation comes with a real danger.

«What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it». Herbert Simon.

Information consumes the attention of people. And attention, as well as time, are valuable resources. As photographers, we deal with one kind of information, visual information, on many more occasions and more than people not involved in photography. We should be more trained to recognize meaningless information, which becomes noise, and to realize that

«[...] such a wall hides an endless invisible reality of which we know little or nothing, of which we have no image». Gigliola Foschi, Le fotografie del silenzio. Forme inquiete del vedere (Photographs of Silence. Restless forms of seeing). Mimesis, 2015.

Visual culture is a valuable talent to cultivate in such times. The ability to see doesn’t wear out when shared.

«Sacred dreamers took papyrus into the incubation room. For Romans, it seems, dreams were had in order that they could be written down. Aristides claims to have written more than 300,000 lines in the dream journal he used as his book’s raw material. Scholars later call that journal we will never get to read “the rejected way” of telling the story». Anne Boyer, The Undying. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.

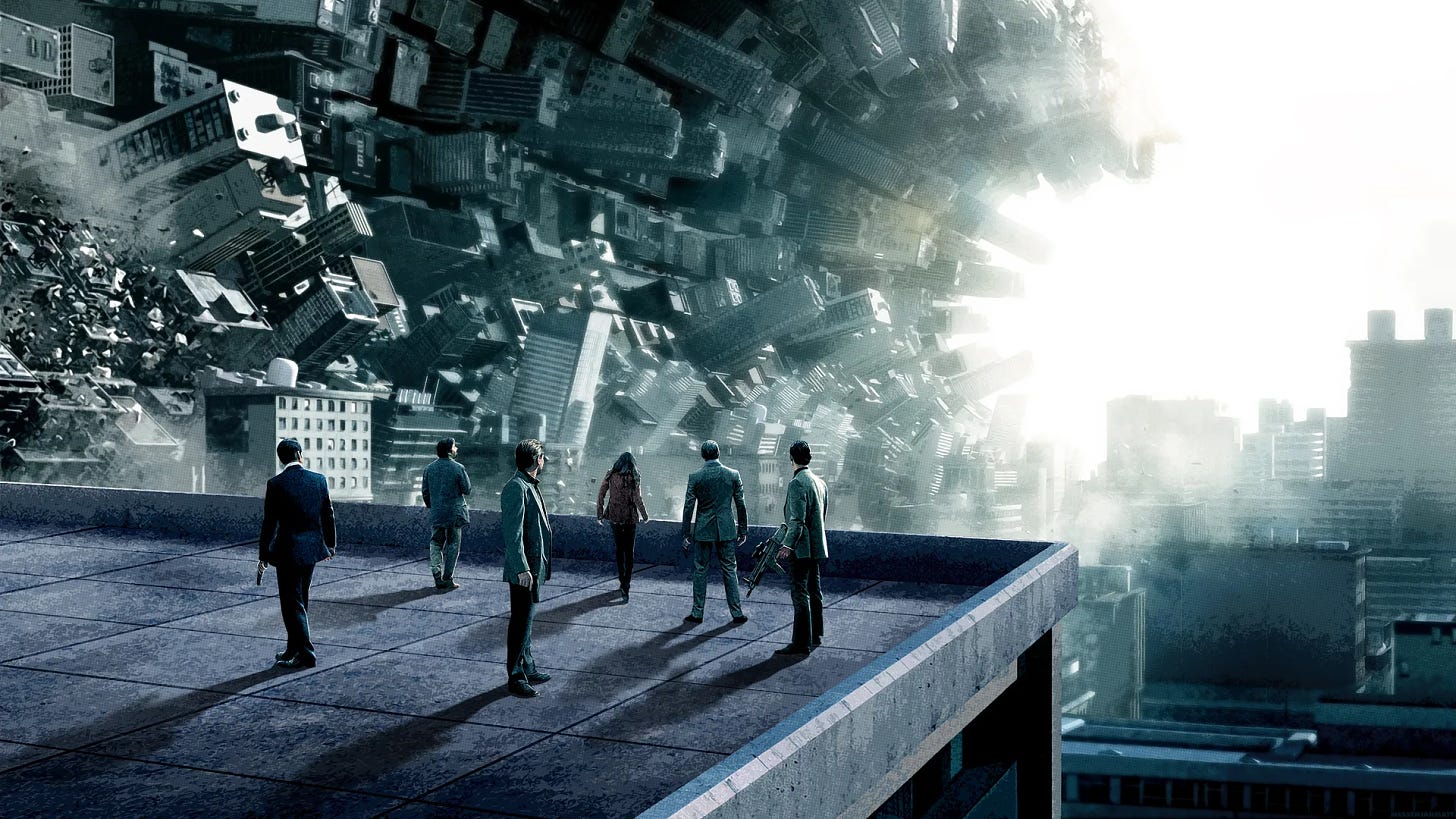

We build a world whenever we put together photographs in a series. We we also make it in each image, selecting and arranging the elements of the frame, but I think the concept is more evident by talking about series.

Our photographic world has its own architecture, rules, and logic and doesn’t necessarily reflect the objective reality of the physical world. We can mix time, connect distant things, and create new concepts.

When the time comes to publish a photographic project (if it comes, it is not compulsory), it is as if we open this world to others. We invite them in; we are hosts. Our world can also be very bizarre and absurd. Still, we can accompany people inside our space, point out the essential services, give basic instructions to orient themselves and show the emergency exits. We must be ready to retrieve those in danger of getting lost and defend our building from vandals. And give the freedom to leave to all those who find nothing of interest there.

«There is, of course, a return to this genre with a contemporary group of ‘art saucers,’ who are trying to convince people that a lackof information in a picture constitutes a mystery. ‘Bet you can’t guess what this is a picture of?’ Why is this interesting? Many writers such as James Joyce, William Carlos Williams and William Burroughs, have tried breaking the form in their attempts to get away from a traditional narrative in order to embrace a larger emotional and intellectual landscape. They are less interested in ‘factual truth’ than emotional truth. This is not the same as withholding information in order to create something for the appearance of mystery.

[…]

Art lives in the tension between abstraction description». Philip Perkis. Teaching Photography: Notes Assembled. OB Press and RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press. Kindle Edition

Or we can do nothing and passively accept the consequences. Let our world be stormed, destroyed, or ignored. I don’t find it a wise decision. But this is my opinion.

Communication is any information that considers who issues and who receives it. It’s a collaboration, a pact to discover something new, build a story, even a little piece each. Why not?

Jackie Mansky, Zócalo Public Square, The Surprisingly Long History of ‘Choose-Your-Own-Adventure’ Stories.

I have a quote in mind that I could not dig up before this article came out. It can be found among the papers in MoMa’s Seeing Through Photographs course.

This happens when it comes to personal projects. Usually, commissioned work has predefined constraints and references, but not necessarily.