#EN1.8 Between Vulcan and Mercury

Multitasking and capacity-constrained systems.

Mercury [Hermes]. Wood engraving by Jonnard after W.B. Richmond, 1866. Source: europeana.eu. Eruption of Mount Etna, 1766. Source: europeana.eu.

To what extent does multitasking get along with creativity?

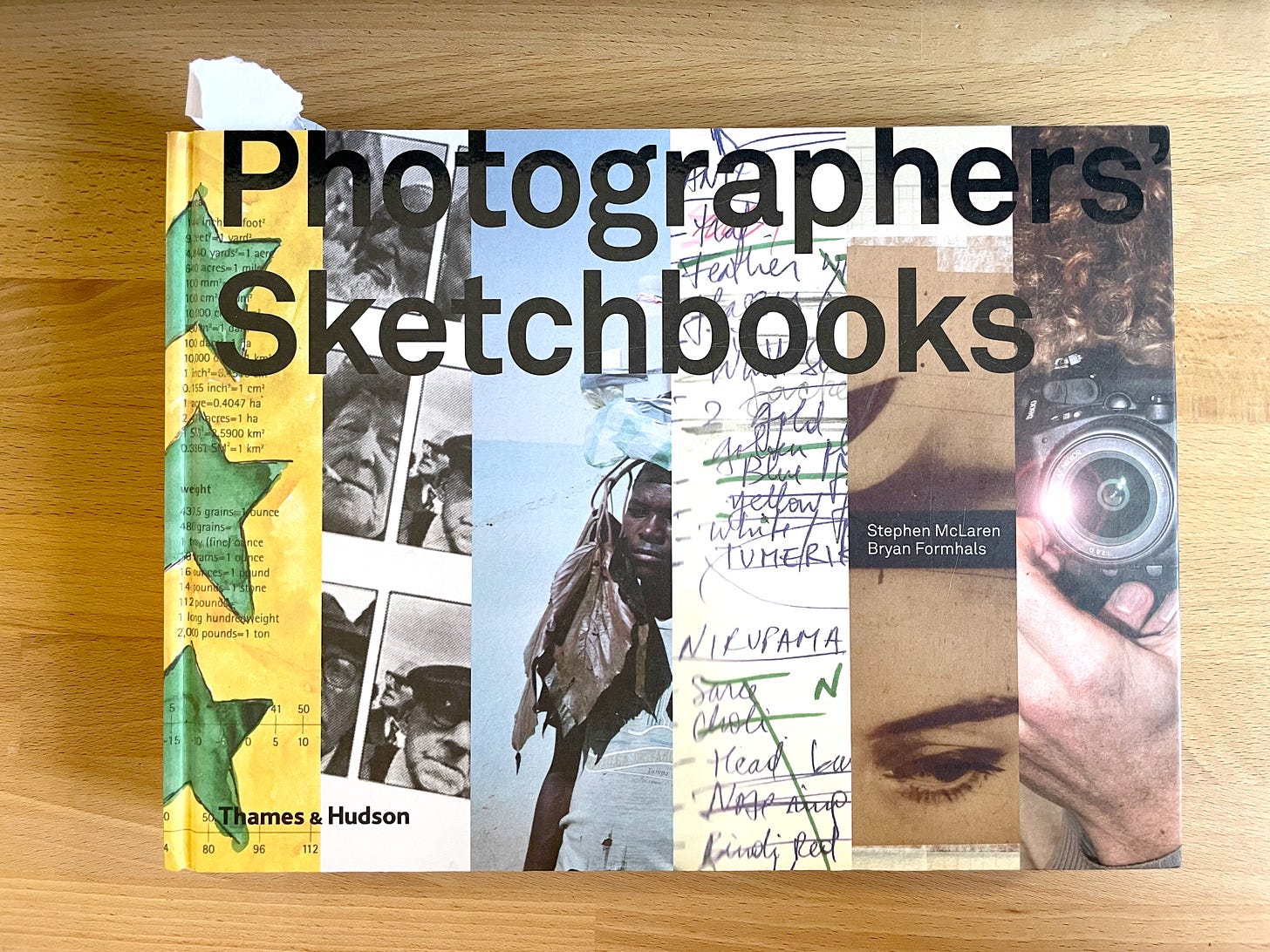

I wonder because I often feel that I carry on the creative practice (whether photographing, studying some book, or other) always in parallel with something else. Finding a space and time that is entirely free, whether physical or mental, is challenging.

«Intellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom». Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own. Booklassic, 2015.

Humans are good at distributing their attention over multiple tasks. Compared to other mammals, multitasking is easy for us. We can answer a phone call while making dinner or drive and talk to the person sitting next to us. We can work and reply quickly to a bunch of urgent emails (well, sort of).

When needed, our brains use strategies to divide cognitive resources among moderate to complex tasks. Our gatherer ancestors had to pick berries while casting one eye on their offspring and another on any predators nearby (although it is more likely that there was some task organization at some point, so there were sentinels, nannies, and gatherers)1.

Biology allows us to do it, cultural evolution supports it, and society stresses it. Multitasking is possible but always has a cost, which is the cost of switching from one task to another, the cost of switching.

«According to Meyer, Evans and Rubinstein, converging evidence suggests that the human “executive control” processes have two distinct, complementary stages. They call one stage “goal shifting” (“I want to do this now instead of that”) and the other stage “rule activation” (“I’m turning off the rules for that and turning on the rules for this”). Both of these stages help people to, without awareness, switch between tasks. That’s helpful. Problems arise only when switching costs conflict with environmental demands for productivity and safety.

Although switch costs may be relatively small, sometimes just a few tenths of a second per switch, they can add up to large amounts when people repeatedly switch back and forth between tasks. Thus, multitasking may seem efficient on the surface but may actually take more time in the end and involve more error. Meyer has said that even brief mental blocks created by shifting between tasks can cost as much as 40 percent of someone's productive time». American Psychological Association, Multitasking: Switching Costs.

For decades, computer science has been concerned with multitasking strategies and context switching, assessing the resources a processor commits to shifting from one task to another or from one process to another. Psychology studies these costs, especially in relation to sensitive occupations, where a half-second decision delay could cause significant damage (as in the case of air traffic control). These are energies and resources consumed to get from one task to another without adding processing.

We need always to weigh costs against benefits. Hence, multitasking makes sense when it leads to an advantage in overall task performance when the effort pays off. This is why we speak, in fact, of multitasking strategies.

So, since it is so difficult to find time to devote just to photography, and since every creative practice needs bills paid and dinner served on the table every night, are there strategies for multitasking that allow you to organize your time and activities so that you can get everything done effectively?

Yes, they do exist. Do they work? It depends.

First, we must understand that every new strategy or habit we adopt has a learning cost. Simply put, it takes time and effort to learn it and “make it work”. Second, we are different individuals, and contextual factors should also be considered. What works for someone at a given time may not always be effective for everyone.

Some brains benefit more from multitasking than others due to biological, neurochemical, or experiential factors. Some tasks are more compatible than others to travel in parallel, while others inhibit each other. There are environmental, contextual, and dispositional factors.

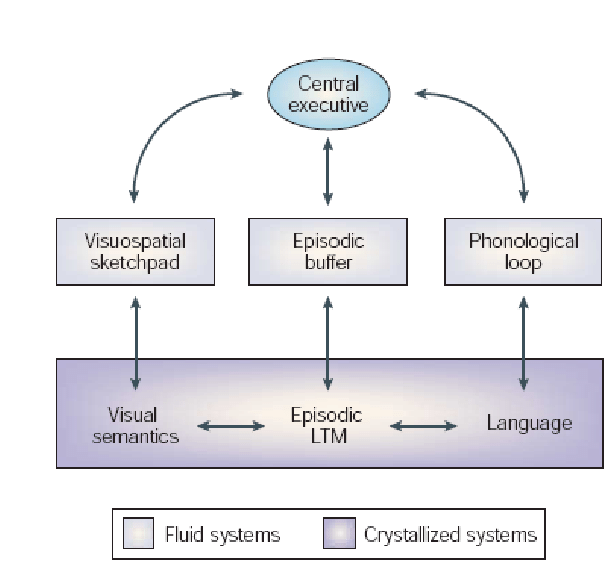

I can’t watch a movie while writing this article. Still, listening to music while revising is relatively easy. In the former case, the two tasks are competing and put so much stress on working memory (working memory).

People generally talk about memory as if it were a single entity. Still, memory is a modular and distributed system, even at the brain structure level. In “typical” amnesia, the person forgets past events but can learn and remember new events and notions. But there are also very different cases, such as H.M. studied by Brenda Milner, who, after an operation to remove the hippocampus, lost the ability to acquire any new notion.

There is a procedural memory where we save the "how to do what" through experience and practice. We can drive and chat, but the first time we got behind the steering wheel, how tiring was it? Driving a vehicle (and playing an instrument) is one of those activities where multitasking becomes easier with practice because there are tasks that go into procedural memory. We can do them automatically with a low cognitive cost.

Working memory is short-term memory. It has a limited capacity and can hold information for only a few seconds. Working memory allows us to process information, which is the basis of many other faculties and systems. Many studies believe that abnormalities in the functioning of working memory are among the underlying factors in autism, ADHD, or cognitive deficits related to depressive syndromes (but research results are not always homogeneous, and there is still a great deal to be studied in this field).

This last sentence doesn’t convince me much, especially the use of the term abnormality, because it implies a greater or lesser distance from what is defined as normal. But who is it that defines the norm? What is the standard if not a reference point and not a biblical commandment set in stone?

Psychology as a science is a very young discipline. One cannot hide that the “norm” was the healthy white man for a long time. It takes time to change the methods and tools and achieve the results. The more I study, the more I see the weaknesses and distortions. Which is good because what you know, you can work on.

Throughout compulsory schooling (twenty to thirty years ago), I was taught that the best way to study was to stay focused without distractions for as long as it took to finish the task (even hours)2. The motto was: finish what you are doing before moving on to something else. No multitasking, then. For some, however, this equals torture. Not to mention that our cognitive abilities are always tied to a body, so moving, gesturing, or receiving other stimuli can support thinking. Sometimes, moving from one task to another creates pauses, in the form of forgetting, that help develop new ideas.

«It’s probably a good idea to not rush to answer questions. [...] We need space to think before we answer questions with any depth of engagement. [...] Margins are incredibly, incredibly, important». Ian Lynam, The Impossibility of Silence: Writing for Designers, Artists & Photographers. Onomatopoee, 2020 edition.

Very often, techniques and tools described in texts to enhance memory are proper. Still, it’s rarely a universal benefit. Sometimes, they are mnemonics, such as the method of loci, which are helpful for specific chunks of information (such as ATM codes or phone numbers) but serve little purpose in training memory in general.

The only fundamental and practical concept (perhaps for anyone) is to remember that we are “systems” with limited capacity and that all stimuli we receive are processed somehow, requiring resources.

We need to recognize and find the systems and contexts that work best for us, whether they are extended periods of concentration on one big issue or alternating between many smaller, quicker tasks (perhaps micro-problems), and remind ourselves that even the most mundane stimulus, such as a notification that appears for two seconds on the phone screen at the periphery of our field of vision (or a vibration, or a sound) is an interference.

None of the people I know can freely exercise their creativity without other commitments or thoughts. Everyone pursues their own path in parallel with family, work careers (even if in the same field, as with photography), daily problems, and interruptions that seem more important and come from all sides.

The most creative and productive people I know are disciplined and adamant about defending their time and space. It is by no means easy. The sad truth for most of us is that we always experience creativity in parallel or alternating with something else as a low-priority activity.

Many creative practices, including photography, need non-productive, repetitive times, and that is where we squeeze in the other processes, the notifications, the quick message. These are short interruptions, but they kill the rhythm of the practice, pull us away from what we are doing, and pollute the ecosystem in which we develop our ideas.

«Ideas are cheap and abundant; what is of value is the effective placement of those ideas into situations that develop into action». Peter Drucker.

A polluted ecosystem needs energy and resources to be restored. It is not so easy, just as it is not easy to convince oneself that creative practice is fundamental3. It would be best if you had an ecosystem yourself (which may include a physical space) in which it is easy to win, especially in the beginning, to start creating a habit. If I have little time to devote to my creativity, even one hour a week, it is improbable that I can save a whole day for it. Unlikely, not impossible, but very difficult. The most significant risk is to be able to carry the commitment for some time, holding out until it becomes too heavy, beginning to create frustration and fatigue.

Playing to win means creating a space for myself to cultivate something I enjoy, perhaps sacrificing something that doesn’t weigh me down. Even if it’s 10 minutes a day. And to keep going like that, consistency rewards. Like driving: with time and practice, some processes will become automatic and cost less effort. We will learn to recognize which things we can carry on in parallel and when we need more concentration. It will be conscious and balanced multitasking, like an orchestra, and not the chaos of a chicken coop where every hen requires attention.

«Vulcan’s concentration and craftmanship are necessary for writing Mercury’s adventures and metamorphoses. Mercury’s mobility and quickness are the necessary conditions for Vulcan’s endless labors to become bearers of meaning». Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Mondadori, 2016.

In my experience, removing contact with any internet-connected device or screen is very helpful. So many people recommend it. They are too distracting, even with all the notifications turned off. Technology is not evil, but I have developed over the years a conditioning whereby every time I have an empty moment, I reach in, touch, search, and interact with my phone. Unconscious associations are the worst to unlearn (and can sometimes lead to addiction). Technological devices do not create the problem, but how we use them, even when the behavior becomes automatic.

«Different, however, is to say that the continuous use of “external minds”, such as a network-connected smartphone, introduces new strategies in using the brain’s capabilities. [...] the continuous availability of Google changes the information storage and retrieval style of those who use it most often because there is a tendency not to put inside the head what is known to be retrievable in this “external mind” [...] integrating natural with artificial memory». Paolo Legrenzi, Storia della psicologia (History of Psychology). Il Mulino, 2012

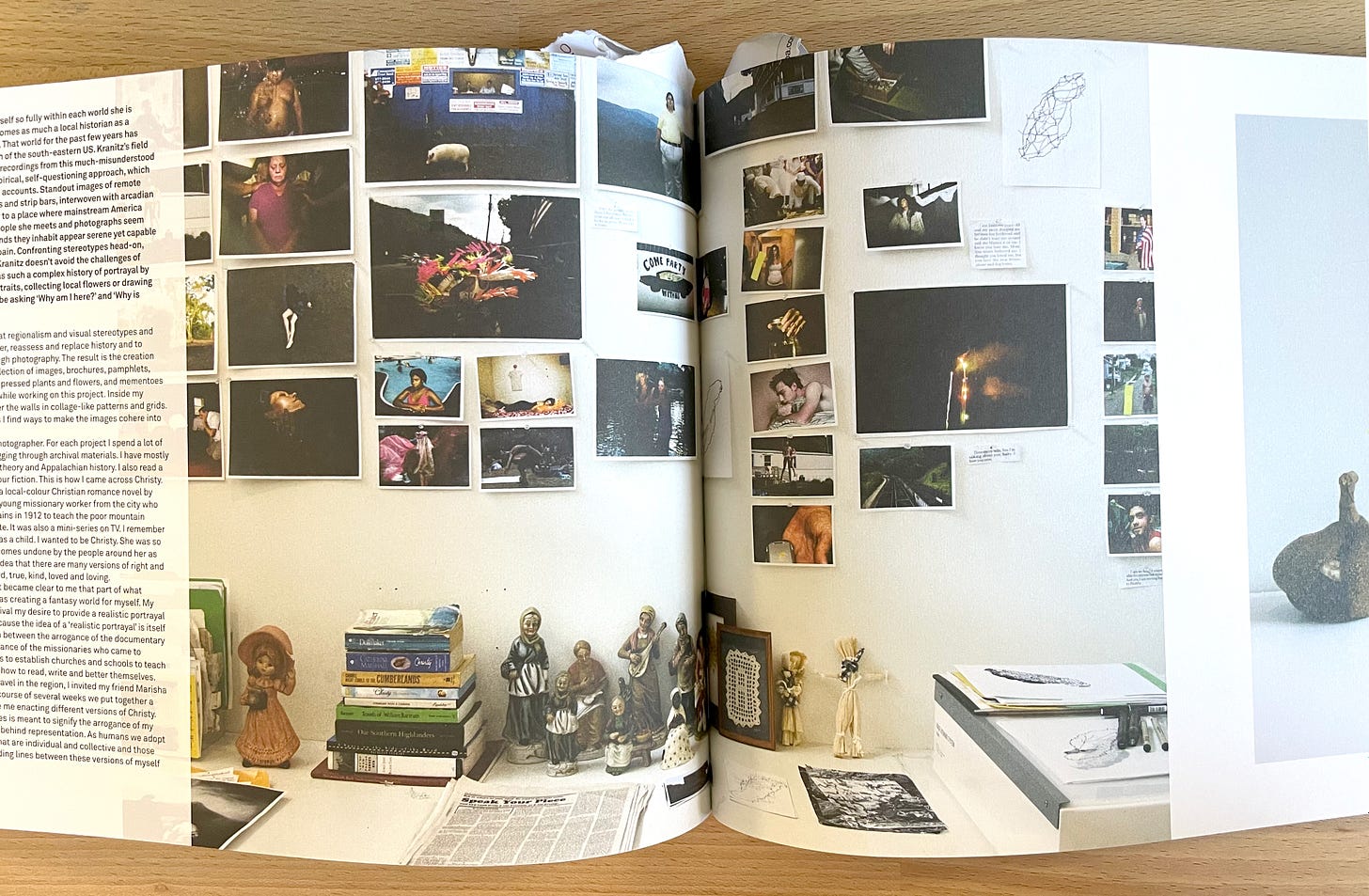

According to the extended mind thesis, in a nutshell, mental faculties would not only be located in the brain or body but would also extend outward. The use of the internet, but also the development of printing, would have changed our cognitive processes. It is a very fascinating theory (although it is still young and has a lot of flaws), especially when working with photographic archives.

«The writer’s work has to take into account different times: the time of Mercury and the time of Vulcan, a message of immediacy obtained by dint of patient and meticulous adjustments; an instantaneous intuition that as soon as it is formulated assumes the definiteness of what could not have been otherwise; but also the time that flows with no other intent than to let feelings and thoughts settle, mature, detach themselves from all impatience and ephemeral contingencies». Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Mondadori, 2016.

Untangling the times of Mercury and Vulcan is challenging. For me, at times, it is also frustrating. Sometimes, I feel lost and unable to pick up the camera, even when I have set aside an hour, two, or three to practice. I feel guilty when I feel I am not doing enough or meeting my expectations. I am learning not to force anything in those moments, to stay within the practice, and not to abandon it to do something else, even if it’s just flipping through a book.

Some argue that women are better than men at multitasking, claiming that since ancient times, they have been used to doing something AND caring for offspring simultaneously. This led to a kind of biological evolution. This simplifies things so much that we can consider it more a curiosity than a scientific theory and a “good tool” for patriarchy.

The best learning strategy, in most cases, is distributed learning. Still, I learned this only at university, when the amount of stuff to study was so large and practical that full immersion was impossible.

Research and creative practices do not depend only on the individual's willpower. Think about school: often, art classes (here in Italy, at least) are just an extra, unnecessary entertainment activity. We need to unhinge this conditioning.